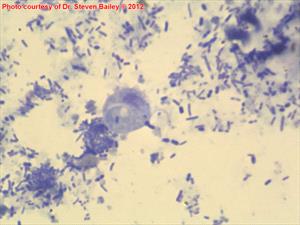

(Try-tricko-monas)

Direct smear

Kittens and cats living in groups have an assortment of infectious diseases to contend with upper respiratory infections, coronavirus, and coccidia, to name a few. Tritrichomonas is yet another infectious organism yielding diarrhea in feline patients, usually with a history of group lifestyle.

Tritrichomonas foetus is a classic parasitic infection of cattle and in 2003 when Tritrichomonas was found to be a cause of diarrhea in the cat, it was assumed that this was the same organism. More recently, genetic research has suggested that the feline organism is a different species, and the name Tritrichomonas blagburni came into play. Years have gone by, and there continue to be arguments over whether these two organisms are actually the same or not. If you are doing your own research, you are likely to find both names used, and it may be confusing. For the purposes of this article, "blagburni" will be used.

Information and recommendations regarding this organism have changed in the last several years, and we attempt to provide the most up-to-date summary of what is known and recommended for the prevention and treatment of this infection.

What is Tritrichomonas blagburni Anyway?

Under the microscope, T. blagburni is commonly mistaken for Giardia, another parasitic flagellate as they both use flagella to move around and both have pear-shaped bodies. The treatment for these two parasites is very different so it is especially important to get the diagnosis right which means that a visual identification may be tricky, especially since both organisms may be present at the same time. Fortunately, there are biochemical tests that have made identification much easier as will be described later on.

How do Cats get Infected?

T. blagburni organisms are shed in the feces of an infected cat. Most commonly, transmission occurs when cats share a litter box, as the organism can live up to 3 days in fecal material and up to seven days at room temperature. Any time a cat steps in the feces of an infected cat, organisms can be transferred to the paws and later licked up during grooming.

What Does it Do to a Cat?

T. blagburni colonizes the lower intestine of the cat causing the mucous and sometimes bloody diarrhea that characterizes colitis. If the colon is biopsied, inflammatory cell infiltration typical of inflammatory bowel disease will be seen. Diarrhea will clear in 88 percent of cats within two years, but the infection will likely persist, and the cat will likely remain contagious to other cats.

Because colitis can have so many causes, it is important to keep this possible cause in mind. Chronic colitis may or may not respond to symptomatic treatment and if a specific underlying cause can be identified and treated, a long-term difficult problem can be potentially resolved permanently. Many colitis remedies will lead to temporary improvement for a Tritrichomonas-infected cat, but the symptoms generally come right back after treatment ceases.

Making the Diagnosis

There are four testing methods that can be used to identify Tritrichomonas blagburni in a fecal sample. A very fresh fecal sample is needed for Tritrichomonas testing. This means the sample must be retrieved directly from the anus with no cat litter contamination, flushed from the colon with a syringe, or obtained with a deeply inserted gadget called a fecal loop. Bringing a sample from home will not be adequate. If the cat has been on antibiotics, this will interfere with testing; the cat should be off antibiotics for at least a couple of days.

Direct Smear

Some fecal matter is swabbed onto a microscope slide, mixed with a gentle saline solution, and examined for flagellate organisms. The feces must be immediately fresh from the rectum. The wetter and more mucous the sample is, the better. Usually, several slides must be examined as the organism is elusive. Standard fecal tests for parasites will not pick up this organism. Refrigeration of the sample will kill the organism and make it impossible to detect. Further, if the patient is on antibiotics the number of organisms available to detect will be greatly reduced even though most antibiotics cannot cure the infection.

While this is a relatively easy test to perform, it only has about a 14% chance of detecting a natural T. blagburni infection. A more sensitive test is generally preferred.

Culture (also called the Pouch Test)

A specific culture bag can be used to grow T. blagburni in numbers large enough for detection. The feces used must be freshly obtained from the rectum, inoculated into the pouch, and the pouch is kept in a vertical position for 12 days at room temperature. The pouch is periodically examined under the microscope for the presence of organisms.

PCR Testing (Polymerase Chain Reaction Testing)

PCR testing is a DNA test for T. blagburni. A larger fecal sample is needed and the test should be done at a reference lab. Many experts prefer the pouch test because it is inexpensive, and leave PCR testing for patients where the pouch test has been negative but the index of suspicion is still high. That said, most small hospitals do not have much experience identifying Tritrichomonas under the microscope so for best accuracy, a better option may be to choose the expertise of the reference laboratory. PCR testing is the most sensitive of all the test methods but is also relatively expensive. Specialized equipment is needed and only a few laboratories are qualified to run samples.

Biopsy

A routine colon biopsy is unlikely to find this parasite; specific stains on the tissue (immunohistochemistry) must be requested and at least six tissue samples must be examined. This is the most invasive form of testing and would not be done right off the bat but if the patient is going to have a biopsy for chronic colitis anyway, it might be a good idea to have the pathologist look for T. blagburni.

A negative test never rules out Tritrichomonas infection, no matter which test is performed.

Treatment

The only drug that is felt to be reliable against T. blagburni is ronidazole, and its use is far from straightforward. Here is what to know:

- Ronidazole must be compounded to get a dose in a suitable size for cats.

- Ronidazole is not licensed for use in cats; it is a poultry antibiotic. It also tastes really bad and should be provided in capsules rather than as an oral liquid to avoid the taste.

- The owner must wear gloves when handling ronidazole as it is carcinogenic.

- The most common side effect in cats is neurotoxicity, which means it is not appropriate to use ronidazole as a trial to see if a cat with colitis improves on it. Ronidazole should be used only in confirmed Tritrichomonas patients.

- Neurotoxicity manifests as loss of appetite, incoordination, and possibly seizures. Some experts recommend engaging the cat in play on a daily basis to assess muscular coordination and agility.

- Cats being treated should be isolated from other cats in the home to prevent reinfection.

- It is not possible to fully confirm that an infection has been eradicated as a negative PCR test does not rule out infection. Experts recommend a PCR test in one to two weeks after treatment and again 20 weeks after treatment as the closest we can come to confirming eradication.

- Ronidazole is usually given once daily for two weeks. The diarrhea should be resolved by the end of this course. Response to treatment may be enhanced by using a high fiber diet and probiotics.

In the past, several different antibiotics have been reported to be effective but it turns out that this is probably an overestimate since 88% of cats will resolve their diarrhea spontaneously within 2 years. They will still be infected, or at least 57% of them will be, but they will have normal stools, and they may relapse with stress.

One treatment option is to simply wait for resolution if the household does not have a large number of cats and the diarrhea is not excessive.