Veterinarians in Arizona no longer need to see patients in the flesh due to a new law that makes it easier to practice remotely by softening a requirement for a hands-on physical exam first.

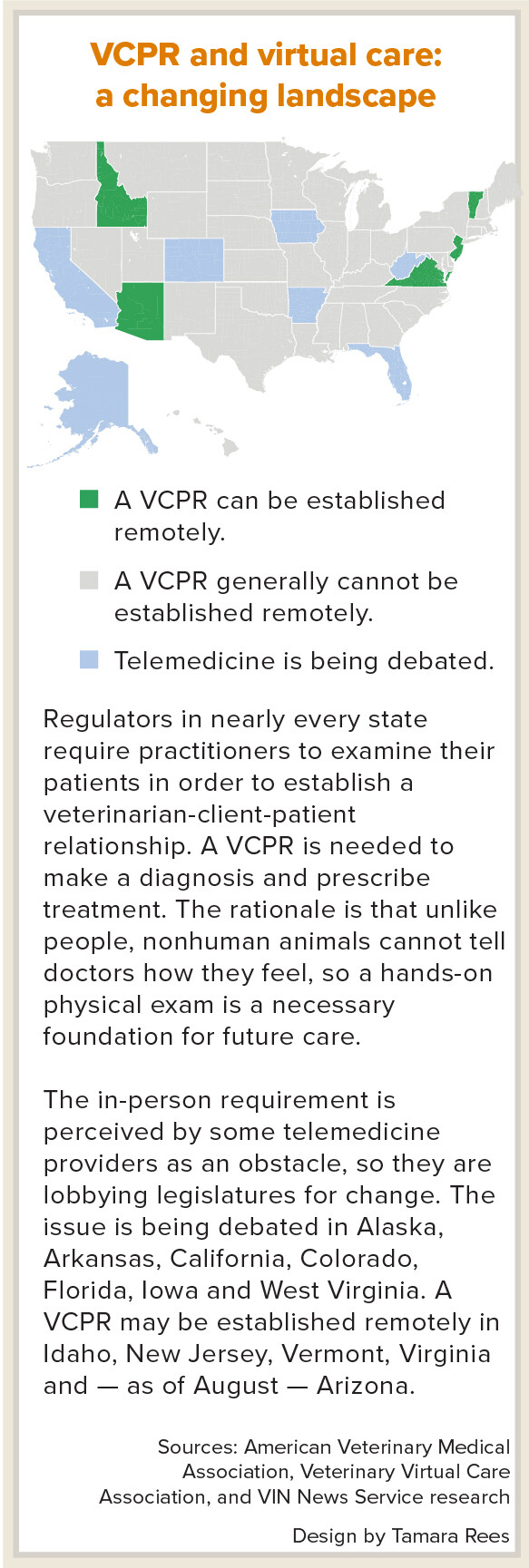

The change, effective Oct. 30, is intended to expand access to veterinary care in Arizona, which joins four other states in bucking a long-established principle that in order to diagnose and prescribe treatments, a veterinarian-client-patient relationship, or VCPR, must be initiated in person.

The development is the latest in an ongoing debate about whether veterinary medicine should follow human health care, which permits telemedicine in all 50 states without an initial hands-on exam.

Most states forbid the same for veterinary medicine, but pro-telemedicine lobbyists are fighting vigorously for change. Lawmakers and regulators from California to New Jersey are embroiled in the virtual care debate as direct-to-consumer telehealth vendors such as Chewy and Walmart vie for a piece of the online action. Chewy recently launched a chat-based platform that offers customers a way to virtually connect with a veterinarian about their pet's health. Walmart has partnered with telehealth provider Pawp to offer subscribers of Walmart Plus, an Amazon-like shopping platform, free on-demand virtual access to veterinarians.

Organized veterinary medicine, meanwhile, is at odds over whether virtual tools can sufficiently substitute a hands-on exam. American Veterinary Medical Association policy opposes establishing a VCPR remotely, owing to the fact that veterinary patients can't speak, making an in-person physical necessary. Policy by the American Association of Veterinary State Boards contradicts that stance.

The regulative landscape is similarly convoluted, with lobbyists on both sides.

In Arizona, legislation to drop the in-person-exam requirement drew almost unanimous support in the Legislature, reflecting a strong coalition led by the Veterinary Virtual Care Association and Animal Policy Group — two industry-supported organizations with Mark Cushing, a political strategist and former litigator, at the helm. Faced with losing the battle to maintain the face-to-face VCPR requirement, the AVMA and Arizona Veterinary Medical Association opted to strike a deal on amendments in exchange for their neutral stance on the measure.

Under the original version of SB 1053, a VCPR could be established by audio-only telephone or video-based communication. The legislation that passed allows veterinarians to "obtain current knowledge" of patients via real-time video communication and requires that they obtain informed consent from the client. Medications prescribed virtually are limited to a 14-day course of treatment that can be renewed for another 14 days if the animal is reexamined remotely. Controlled substances are excluded.

On May 9, Gov. Katie Hobbs signed the measure. Cushing considers that a win, even with the prescribing guardrails.

"The new Arizona law provides significant groundwork for other states," he said in an interview. "… The VMAs, with rare exception, increasingly default entirely to the AVMA's policy on this issue. But we're seeing that it may not matter when we come in with a coalition of businesses, animal welfare organizations and supporters. That's key to our success."

Climate of deregulation?

Arizona is the fifth state — after Idaho, New Jersey, Vermont and Virginia — to permit a VCPR to be established online. Vermont law offers carte-blanche access, even creating a registry so that out-of-state providers unlicensed in the state can provide remote veterinary care to the pets of residents. Regulations in other jurisdictions are more restrictive. Idaho, for example, permits remote care without an in-person examination except when prescribing medications.

California, the most populous state in the country, is on the front lines of the continuing battle. A bill under consideration, AB 1399, would enable veterinarians to decide on a case-by-case basis whether a patient needs an in-person examination first or can be treated immediately via telemedicine.

The bill unanimously passed the state Assembly on May 31 despite heavy pushback from the AVMA and the California Veterinary Medical Association. Cushing asserts that the broad consensus reflects a desire by lawmakers to meet the public's demand for veterinary care. "Human medicine has had 25 years of success in developing the use of telemedicine. Is there any reason why it couldn't apply to pets? No, absolutely not," he said.

In an email alert ahead of the vote, the CVMA urged the group's 7,000-plus members to lobby lawmakers in opposition, warning that if passed, AB 1399 would harm consumers and damage the veterinary profession by allowing "a substandard level of care … that put pets at risk."

AB 1399 revises the definition of VCPR such that a veterinarian must have "sufficient knowledge of the animal patient to initiate at least a general or preliminary diagnosis of the medical condition … through a recent observation and examination, either in-person or using real-time video communication, or through medically appropriate and timely visits to the premises where the animal is kept."

The state's existing definition is among the nation's strictest. It indicates that a VCPR must be established in person for each diagnosis made and treatment provided, even within the same year. "For example, a veterinarian who examines, diagnoses and treats an ear infection must establish a VCPR for that given condition," explained Dr. Grant Miller, CVMA director of regulatory affairs, in guidance he authored for members. "If the same animal comes in a month later with lameness, the VCPR for the ear infection cannot be used to provide medication or other treatment for the lameness."

The CVMA will have an opportunity to reiterate its stance on July 10, when the Senate Committee on Business, Professions and Economic Development holds a hearing on the measure. The legislative session runs through Sept. 14.

Rolling back access

"If this gets through in California, that's huge; I don't think there is much that can stop it," Cushing said, predicting that "there will come a time when veterinary telemedicine is allowed in every state."

He may be right, if human medicine is any indicator. Remote care has become mainstream in human health care, so much so that an article in Forbes mused in 2020 that veterinary telemedicine could be "the next big thing."

He may be right, if human medicine is any indicator. Remote care has become mainstream in human health care, so much so that an article in Forbes mused in 2020 that veterinary telemedicine could be "the next big thing."

Officials in many states may not agree. Most have been quick to reinstate restrictions that were eased to permit telemedicine during the Covid-19 pandemic, and in some cases, regulators are strengthening the VCPR barrier. Michigan, for example, briefly permitted telemedicine without being preceded by an in-person exam but recently reinstated that requirement.

And New Jersey, one of the five states that have dispensed with the requirement for a hands-on exam, is considering reversing course. The state had eliminated the in-person exam requirement in a 2017 law aimed at human health care. Veterinary medicine was inadvertently swept up in the change. New Jersey veterinary authorities are pushing for an exemption.

Officials in other states aim to avoid such a scenario by clarifying veterinary regulations. Alaska, for instance, had been silent on VCPR parameters. Last month, the Alaska Board of Veterinary Examiners promulgated rules that an initial hands-on physical examination is needed for a VCPR to be established.

"Once established, a VCPR may be maintained by electronic or telephonic means during the 12 months that follow the initial exam or premises visit," the regulation says.

State boards in Arkansas, West Virginia and Iowa recently adopted similar regulations. Last year, the Florida Veterinary Medical Association managed to defeat HB 723, which would have allowed a VCPR to be established remotely. Measures recently enacted in Hawaii and Kentucky address telemedicine by stipulating a timely in-person exam as a VCPR condition.

Online vendors may have trouble keeping up with all the changes. Dutch Pet, for example, advertises that it operates in states such as Ohio, where the in-person requirement for establishing a VCPR has never been relaxed, even for Covid.

Invited to explain, officials with the company did not respond to the VIN News Service. A query sent through the company's web portal generated an email coupon for "$10 off vet care over video." Jack Advent, executive director of the Ohio Veterinary Medical Association, is perplexed.

"This wouldn't be the first time someone outside of Ohio hasn't done their homework and read Ohio law," Advent said. "Like I always tell my members, the state isn't going after Dutch Pet ... they'll be going after you, and you'll suffer the consequences. Corporate entities won't be the ones on the hook; they're not the ones with the license."

Cushing laments when associations in states such as Ohio align with the AVMA.

"What has stopped telemedicine has been those states where the Legislature simply turns to the VMA and says, 'What do you want us to do?' and the VMAs are very conservative, and they typically follow the AVMA policy," he said. "Or there's a member of the Legislature, as in Colorado, who's a veterinarian and has some power and is strongly opposed to telemedicine."

That's a reference to Rep. Karen McCormick, who worked at Colorado State University and operated her own veterinary practice for 16 years before entering state politics. In January 2021, she began her term on the Colorado House of Representatives and now chairs the House Agriculture, Livestock and Water Committee.

Many believe she stands in the way of major shifts in the veterinary profession in Colorado. Feeding off a purported lack of veterinarians, public pressure has mounted to expand technician roles and create a new midlevel practitioner in Colorado. The initiative is coupled with calls to lift state restrictions on veterinary telemedicine, which require an in-person physical examination before providing remote care.

A bill was introduced to do so. McCormick introduced a counter bill in support of existing law. The legislation clarified that a VCPR is established by a veterinarian via in-person physical examination and set guidelines for telemedicine in the state.

With the animal welfare and veterinary communities deeply divided, House leadership elected not to introduce either bill and instead, pressed for a single consensus bill. The attempt to compromise "proved to be impossible due to opposing viewpoints, and as a result, no bills related to veterinary medicine were introduced," the CVMA said in a legislative recap.

The General Assembly adjourned on May 8, but the battle is expected to continue in the Statehouse in 2024.

Using telemedicine daily

If it were up to Dr. Audrey Wystrach, relaxing restrictions on veterinary telemedicine, within limits, would be easier.

"Look, Blockbuster video had a chance to buy Netflix and said no. Instead, they told Netflix, 'Good luck,' " she said. "Traditional veterinary medicine needs to adapt and meet the consumer. Veterinarians need to take control of the narrative, and drive industry change."

As the founder of Petfolk, a chain of brick-and-mortar, mobile and telemedicine services across at least four states, Wystrach is in the business of trying to make that happen. She started the company in 2019 but got into telemedicine organically, as a solo practitioner fresh out of school who serviced equine and small animal patients across a 60-mile radius of rural southern Arizona.

In practice nearly 30 years, Wystrach said she has "been using telemedicine as a huge part of my practice forever. I started out with a gigantic territory of clients and turned to telemedicine as a means for survival. I started by charging for phone consultations." Doing so enabled her to manage her caseload "without working 24 hours a day, seven days a week," she said.

She required her equine clients — owners of mostly performance and show horses — to purchase custom first-aid kits so she'd have the option of treating a patient by phone in case she couldn't get on site quickly. Often, the kits contained pain management drugs and other medications.

"I managed a large sector of my clients with the addition of telemedicine and teleadvise, predominantly by telephone back in the early 90s," Wystrach recalled. "I can't even count how many cases of high-performance horses that had early episodes of tying up. … It was nice to get a dose of acepromazine or banamine on board. The customer could call you back and give you a status update, together we would determine if a visit was needed.

"It was not only required for patient management," she continued. "It was also required for my quality of life, because I had three kids and a husband who traveled five days a week. I was a solo practitioner — with 11 employees, but I was the only doctor."

Asked whether it was legal to provide clients easy access to such drugs, Wystrach responded that regulators were lenient.

"We trusted the practitioner, back then, to make the right decisions," Wystrach said. "I was doing the right thing for my clients. I don't remember even saying, 'is this legal or not legal?' Veterinary medicine has been practicing telemedicine for ages … and now everybody's getting their hackles up, so we're assigning a name to it."

Wystrach employs 20 veterinarians at Petfolk, which has 13 mobile units in Florida, Georgia and the Carolinas, along with five traditional clinics.

Asked if they use telemedicine, she replied: "Some do and some don't. … Our veterinarians get to choose their own adventure."

Wystrach said as much during recent testimony before lawmakers in Florida, where companion bills in the House and Senate called for revising the state veterinary regulatory code to ease restrictions around remote care. Current administrative rules in Florida forbid veterinarians from using telemedicine — defined as diagnosing and prescribing drugs by telecommunication or audiovisual means — unless they've seen the patient within 12 months, according to the FVMA.

The House measure drew unanimous support, but the legislation, opposed by the AVMA and FVMA, stalled in the Senate and did not pass before the Legislature adjourned on May 5.

Wystrach said in frustration: "The AVMA is a membership organization, not a regulatory body, that shouldn't be telling me or anyone else how to practice. We should be trusted to make appropriate decisions about when to use telemedicine."

Florida is a battleground

The FVMA, with lobbying support from the AVMA, has for years been resisting attempts to deregulate telemedicine in Florida. The state became ground zero in the battle in 2021, when Dutch Pet hired a powerful lobbying firm to push deregulation. While administrative rules in Florida restrict telemedicine based on the federal VCPR definition, which applies to extralabel drug use including compounded products and veterinary feed directives for food animals, the state veterinary practice act does not address remote care in its VCPR definition. Rather, it defines a VCPR as "a relationship where the veterinarian has assumed the responsibility of making medical judgments regarding the health of the animal and its need for medical treatment."

There's no in-person requirement in the statute's VCPR definition, Cushing observed: "That's why every year, the Florida VMA has a bill, and every year, we do. They want to tighten it, and we obviously don't."

Hoping the ambiguity might work in their favor, Dutch Pet championed two bills during the 2021 legislative session to cement relaxed telemedicine rules in the state. Both were defeated, in large part due to a defiant FVMA.

This year's fight again ended in a stalemate. In a blog post dated May 5, the FVMA referenced its own failed attempt to cement telemedicine guardrails through SB 554, which would have permitted veterinary telemedicine with "the proper establishment" of a VCPR.

FVMA past president Dr. Rick Sutliff clarified the group's stance: "The FVMA has for years promoted and offered bills that would place telemedicine, with clear definitions, into statute as opposed to just in board rules. Our goal is to have this accomplished, but with the condition that the VCPR can only be established or reestablished in person with a physical exam at least once every 12 months."

He added: "The entire telemedicine debate is not about being able to do telemedicine; we all have been doing it since Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone. ... The entire argument comes down to how the VCPR is established, and almost all states require that to be done with an in-person physical exam."