Whitchurch

Gentle Care Animal Hospital photo by Hailey Mann

No longer masked, Dr. Kelly Whitchurch examined a patient this week at her southwest Missouri hospital. The practice recently returned to working without masks as part of a rollback of COVID-19 prevention measures.

It's been a tough year for Otto and Oakley, a pair of gray-muzzled mutts who have belonged to Joe Hass since they were puppies. They hit a run of bad health — cancer (Oakley), torn knee ligaments and severe constipation (Otto) — all of which necessitated repeat visits to hospitals that were not letting owners in with their pets, to reduce potential spread of the virus that causes COVID-19.

"I'm fine with it if that's my only option, but I don't like curbside," said Hass, a website developer in Tennessee. "Curbside" is shorthand for handing over your pet to veterinary staff outside the clinic, a protocol many practices adopted to comply with social distancing guidelines. Hass recently moved from the San Francisco Bay Area, where, in pre-pandemic days, his veterinarian let him be present for all procedures other than surgery.

Back then, neither dog had exhibited stress at the veterinary clinic, he said. That's no longer the case. "Last time, they couldn't draw blood from Otto because he wouldn't settle down," Hass said. "That's never happened before."

When Hass discovered a growth on Oakley's ankle that turned out to be cancerous, he and the dogs had just moved to Chattanooga. He had to drop off Oakley at a clinic that he'd never been in, and to consult with a veterinarian he'd never met face-to-face. "It's been really awful," he said.

This month, Hass' new clinic announced that clients once again can accompany their pets inside.

Across the United States, veterinary hospitals, like businesses of all stripes, are navigating a new reality as most jurisdictions end nearly all pandemic-related restrictions and many Americans embrace some semblance of normal life.

As they have since COVID-19 was declared a pandemic in March 2020, veterinarians are responding in diverse ways. Some are sticking with curbside for the time being, while others are embracing a hybrid model that allows clients in with pets on a limited basis. Some never adopted curbside service in the first place. Mask and vaccination rules for staff and clients are evolving and sometimes causing angst. Veterinarians express frustration, confusion, optimism and relief — sometimes all in the same conversation.

Easing into new routines

California this week made pandemic headlines as it dropped most mask requirements for people who are fully vaccinated and eliminated most social distancing and capacity restrictions. The rule change impacts nearly 40 million residents.

Dr. Linda Hall, whose Bay Area practice has two veterinarians and nine full- and part-time support staff, is ready to ease rules at her practice. It's a big turnaround for her.

Hall implemented safety protocols — requiring personal protective gear for staff, implementing rigorous sanitizing and limiting the number of clients in the clinic — around March 13 last year, a week before the state issued a stay-at-home order. That's because she was hearing about the virus from family living in Spain, which experienced one of the world's first surges in infections.

Now, some 15 months later, she's ready to open up. Clients soon will be allowed into exam rooms. However, prescription purchases and drop-offs for veterinary technician appointments will continue curbside. A mask requirement for clients and staff, regardless of vaccination status, remains in place.

Oakley_in_a_cone

Photo by Olivia Van Wormer

Oakley wears an inflatable collar while recovering from surgery to remove a cancerous growth from his ankle. His owner, Joe Hass, moved to Chattanooga during the pandemic. He hated dropping off his dog at a clinic that he'd never been in.

A bigger shift is intangible: There is less apprehension. For example, if a client pulls down their mask, "We don't have to worry; it's not as big a deal right now," Hall said, noting that her entire staff is vaccinated. "Now it's a courtesy. Before, it was life and death."

She said she'll miss the efficiency of curbside — something several other veterinarians who talked to the VIN News Service echoed. However, she won't miss clients' anger about being separated from pets.

People have been on edge, she said. Some clients were angry about not being allowed in; others were frustrated by long wait times at the very busy clinic. Hall thinks some of the impatience was because people waiting in their cars couldn't see staff working hard to move things along.

"I'm tired of angry people," she said. It got so bad, she posted a sign at the clinic that read, "Please be kind to our staff. We could not do our job without them."

In Oakland, Dr. Maureen Dorsey never went curbside at her two-veterinarian practice. Instead, she allowed one to two masked clients to accompany their pets into the large waiting room. She used a bench — with an air purifier on it — as a barrier to keep clients distant from the receptionist. Children were not permitted in the clinic.

"I expect this to be standard through fall," Dorsey said, pointing to the general trend of respiratory diseases increasing in the fall and winter. "Who cares what the governor says? We are going to do what we think is comfortable."

Dorsey requires all clients to wear masks because she doesn't want to police their vaccination status.

Her biggest fear has been an infection starting with members of her staff and spreading to the community. Since being vaccinated, she said, "I feel much less terrorized. I am no longer worried at all what my staff are doing after hours. Before, I was really concerned."

Should employers require vaccination?

Many practice owners have had difficulty in persuading all employees to be immunized. One veterinarian told VIN News she offered incentives to employees who were vaccinated, including two hours of paid time off, gift cards and even a day of driving her new Tesla Model X. For some, even that was not enough. Another veterinarian told of an employee who quit rather than be vaccinated.

Some practices are making changes to accommodate the presence of unvaccinated staff. One practitioner will not allow unvaccinated technicians to assist in the tight space of an exam room when clients are present, which means she sometimes has to handle a large or difficult animal on her own.

Pitfalls of requiring vaccines

or giving incentives

In sum, Moore said: "An incentive or penalty program can easily discriminate on many ... grounds if it doesn't take into account the various exceptions and accommodation requirements. And, of course, once you start delving into an employee's medical condition, you better be ready to deal with protecting medical information, handling accommodation discussions, etc.”

Of the eight veterinarians VIN News interviewed, none is requiring employees to be vaccinated.

Employers who would like to have an entirely vaccinated workforce are in a tight spot. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which regulates workplace safety, requires companies to provide safe and healthy working conditions, which could mean requiring employees to be vaccinated, according to Raphael Moore, general counsel of the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of VIN News. However, Moore doesn't recommend it.

He said requiring vaccination or even offering incentives to be vaccinated raise myriad human-resources and legal issues (see sidebar). Rather than hard rules or enticements, Moore recommends educating employees about the benefits of vaccination.

Outside California, veterinarians navigate similar challenges

With county case numbers low, local mandates lifted and all but one employee vaccinated, Dr. Kelly Whitchurch said her two-veterinarian, 13-staff-member practice in southwest Missouri is nearly back to pre-pandemic operations.

"We had (as we have had all along) a discussion about risk, comfort levels, etc., with the staff," she told VIN News via email. "None of the staff wanted to remain masked, so we were OK with that part."

Clients may wear masks or not, as they prefer. No more than two people may accompany a patient to an appointment, and they must call before entering. They are escorted directly to an exam room, and check out from there.

Some business is still transacted at curbside: Medication and food purchases are picked up outside. Pets with grooming appointments are met at the curb. And clients who'd rather stay outside, may.

The central goal is to reduce crowding in the lobby, which Whitchurch said has the side benefit of reducing general stress for everyone — pets, the veterinary team and clients. "A lot of clients worry about walking in and meeting another dog, or having a dog run up to sniff a cat carrier."

Sometimes clients forget to call before coming in or to wait in the exam room to check out. "But honestly, I am just letting it ride," Whitchurch said. "The staff are comfortable, I am comfortable, and the clients are just super excited to be able to be in the building again. I figure we will just slowly morph back to clients coming in without calling."

Some employees have had to climb a learning curve, too. Those hired after the pandemic knew only how to work curbside. With reopening, they needed to be trained to manage in-room appointments.

In Virginia, Gov. Ralph Northam lifted the state's mask mandate on May 28. "The very next day, I noticed many people not wearing masks at the grocery store," said Dr. Ebalinna Vaughn, who owns a small clinic in northern Virginia with three employees.

Vaughn still requires masks for staff and clients, and some clients are pushing back. "So far it has just been comments about being fully vaccinated [and] surprise that I am still requiring masks," she said.

During most of the pandemic, Vaughn has allowed clients into the clinic reception area. She plans to keep them out of exam rooms for a while longer.

"My rooms are not tiny, but right now they feel claustrophobic," she said, adding if the region gets through the summer and maybe early fall without another surge, she might let clients back in the exam room.

Vermont rescinded all remaining COVID-19 restrictions on Monday after becoming the first state in the U.S. to have 80% of its eligible population receive at least one dose of the vaccine.

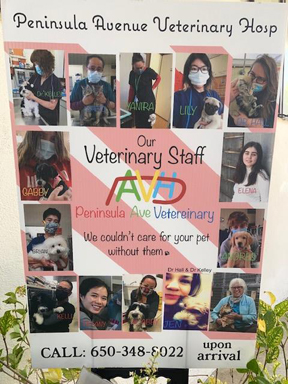

Be-Kind_poster

Photo by Dr. Linda Hall

Early in the pandemic, Dr. Linda Hall, owner of a small practice in California, posted a sign asking clients to be kind to support staff. Like many veterinarians, she found some clients had become ill-mannered to staff. Later, she created this poster to foster kindness and patience.

Businesses and municipalities can continue restrictions if they chose. Dr. Tammy McNamara, a partner in a southern Vermont practice with eight veterinarians and about 20 staff members, is one of those sticking with curbside for the moment.

It feels great to reach the important milestone, McNamara said in an email to VIN News, and it "provides some level of confidence that we will be able to safely open the clinic."

However, she said some younger staff are not yet vaccinated. "We intend to wait until those who choose to be fully vaccinated are able to achieve that," she said. Her clinic plans to allow clients back into the building in mid-July.

Dialing back anxiety isn't easy

To Dr. Steve Valeika, a practitioner in Asheville, North Carolina, with a background in epidemiology, decisions to end most mask mandates and social distancing felt sudden.

He wishes there had been a little more of a buffer for businesses, such as pegging the end of restrictions "to hitting a certain percentage vaccinated, picking a number that we would hit in a couple of weeks, for instance," Valeika wrote on a discussion about the end of mask mandates on a VIN message board.

A consultant for VIN, he has watched as colleagues jousted on the message boards about reopening strategies and governmental policy. He has urged empathy and patience.

"The pandemic began at the same time for everyone, but it's going to end at different times for each individual," he wrote. "Everyone is going to process what we've been through differently and at different rates, and everyone is going to make sense of the new recommendations in deeply personal and individualized ways."

For his part, Valeika anticipated feeling "a lot of cognitive dissonance as I try to reconcile what I know vs. what I feel, as facts are suddenly changing a lot faster than emotions," he wrote. "Luckily, living with uncertainty is one of the fundamental properties of epidemiology."

As risks during the past 15 months waned and waxed and waned and waxed, "what I knew about epidemiology aligned with my emotional desire to protect my family, my community, and myself," he said. "We are finally hitting a period where risks are truly going to be low for a lot (but not all) of us … I know that my alert level doesn't have to be so high, but dialing that down is difficult."