Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

Australia fluid shortage

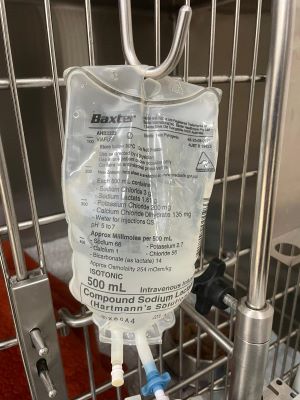

Photo by Dr. Andrew Wester

An IV fluid bag manufactured by Baxter International is among those being rationed by Dr. Andrew Wester and colleagues at an emergency hospital in Melbourne, Australia.

An extended shortage of intravenous fluids in Australia is prompting veterinarians to ration supplies and delay some elective procedures amid expectations that it could take until 2025 for availability to return to normal.

IV fluids are a vital therapeutic in human and veterinary medicine frequently used to to keep patients hydrated, replace essential electrolytes and nutrients, raise low blood pressure and deliver some medicines.

"They're a cornerstone of our treatment," said Dr. Andrew Wester, an emergency veterinarian who's been rationing fluids at a hospital in Melbourne since June. "We can't do a lot of things without them."

Reports of nationwide shortages in the Australian medical and veterinary realms began circulating widely in June and were confirmed by the country's pharmaceuticals regulator in July.

Australian politicians initially suggested the shortage was a global phenomenon sparked by a post-pandemic rebound in demand for surgeries. It appears, however, that the shortage is more or less limited to Australia, which has relatively modest domestic manufacturing capabilities and is more vulnerable to global shipping bottlenecks due to its far-flung location.

"The shortage is affecting a broad range of veterinary practices across Australia, particularly in emergency care settings," according to a written statement provided by the Australian Veterinary Association to the VIN News Service. "However, there is variation in the extent of the impact depending on the size of the practice and their current stock of IV fluids."

The AVA said that although it knows of elective procedures being postponed, "there is no evidence of animals suffering" directly from a lack of fluids.

Veterinary practices, the group added, appear to have been hit particularly hard, in part because hospitals for humans typically are larger and have more financial heft to maintain supplies. "While some human elective surgeries have been delayed, the human sector reports that it has managed to maintain adequate supplies," the AVA said. "The veterinary sector relies on more limited supply chains."

Wester, an American who moved to Australia in 2018, said he's lucky to work for a large corporate chain that was able to secure a decent volume of fluid.

"They've done a good job of rationing amongst the clinics in their group," he said. "But I know of private practices that have had to literally stop doing things because they can't get fluids."

Wester and colleagues are being more "judicious" with IV fluid use, he said — using them only when absolutely necessary. They've also been trying to use 500 mL and 5 L bags when they can, since the shortage is more pronounced for 1 L bags. (The amount of fluid typically needed per patient is influenced by factors like the type of procedure and the patient's size).

"We'll do things like, for cats, pull up fluids into a syringe and administer the fluids with a syringe pump, as opposed to cracking a bag and putting it on a cat or other small animal," Wester said.

Hospitals have been assisted by rationing guidelines issued by the Australian and New Zealand College of Veterinary Scientists (ANZCVS), a professional association for specialists.

Notable advice includes divvying the content of individual bags into appropriately sized and labeled syringes and being more choosy with IV fluid type. For example, the ANZCVS guidelines suggest that a 0.9% sodium chloride solution may be adequate for fluid administration around the time of surgery (perioperative), but only for routine surgeries that take less than an hour.

Should veterinarians use one bag on multiple patients, the guidelines recommend reducing contamination risk by dating and labeling the opened bag, using gloves and alcohol swabbing and avoiding hanging the bag over or near a sink, where the risk of contamination is higher. It is generally recommended that any unused contents of opened bags be discarded after 48 to 72 hours.

The AVA said some practices are sharing fluids with nearby clinics. The ANZCVS is urging practices to order volumes based on their average usage to ensure a fair distribution of stock when it becomes available.

How quickly that stock will materialize is unclear. IV fluids in Australia are supplied by three companies: Baxter International, B. Braun and Fresenius Kabi. Of the three, only Baxter manufactures the products domestically.

The Australian federal government announced on Aug. 27 that it had secured an additional 22 million bags "over the next six months" and that Baxter would "in the coming weeks" expand its local manufacturing capacity. Australia typically goes through about 80 million bags a year, according to the country's health minister, Mark Butler.

How much of the additional supply will go to veterinary practices remains to be seen. A national response group established by the government last month includes the AVA along with the Australian Medical Association, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists and federal and state politicians.

Wester said he has heard of one local distributor for veterinarians expecting a container of IV fluids to arrive from overseas in mid-October. The AVA, too, is hoping more volume will flow into the market before year's end.

"There is suggestion that some relief is expected in the coming months, but full replenishment may not occur until early 2025," the group told VIN News.