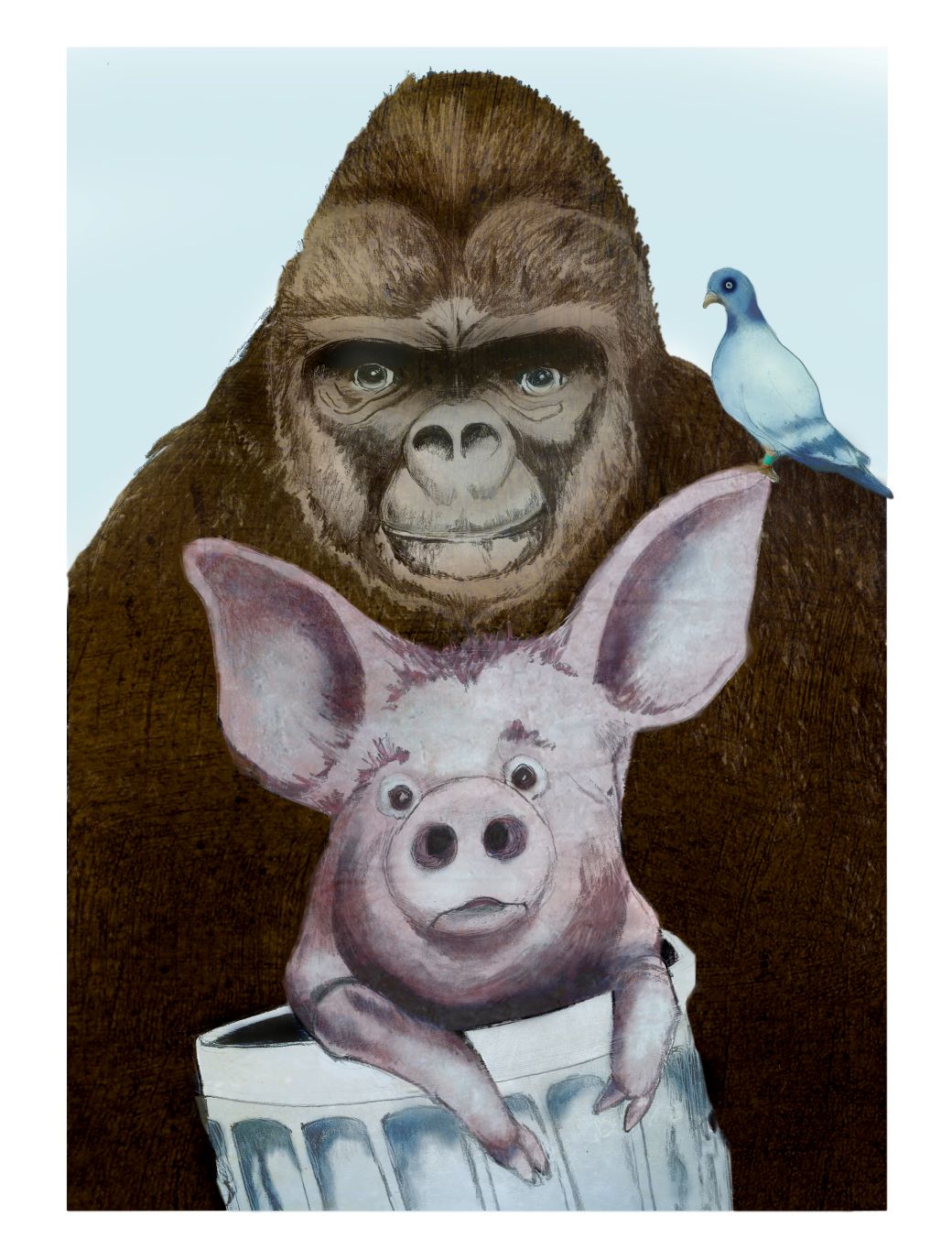

NAVLE Questions art

Illustration by Jon Williams

With 360 multiple-choice questions, it's not surprising that the North American Veterinary Licensing Examination covers the gamut of all things veterinary medicine. But even the most studious of budding practitioners may be taken aback by exam topics that stray from the conventional.

As reported by the VIN News Service in November, more students are struggling to pass the NAVLE, which is required before obtaining a license to practice veterinary medicine in any jurisdiction in the United States and Canada. The story led members of the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of VIN News, to reminisce about their encounters with licensing exams, including the NAVLE and several outdated state tests. On a VIN message board, veterinarians shared anecdotes of peculiar questions and unique study approaches (such as a student leveraging an exceptional memory) and reflected on the difficulty of mastering all of the information.

A selection of their thoughts and anecdotes is edited for length and clarity.

I never took the NAVLE; that was after my time. I took the National Board Examination, Clinical Competency Test and the New Jersey state boards. I just remember that there was a question on the New Jersey boards asking how long you had to boil garbage before it was safe to feed to pigs.

Dr. Kimberly Ashford

Riverside, New Jersey

I clearly remember having a NAVLE question about a racing pigeon. I can't remember what the exact question was, but I do remember the feeling of surprise and a giant "!?" floating in a bubble over my head.

Dr. Megan Ward

Kirkland, Washington

We complain about individual questions (I had so many about human HIV) because we have a tendency to think that we should have all the answers. It's OK that we learn that we don't. It's OK that we learn that a massive stress with unending questions and decisions is really, really rough. I'm betting most doctors who have practiced for as many years as they attended vet school have at least one day where that was true — and where having every answer known to man wouldn't have helped every patient or client.

Dr. Summer Hedges

Wake Forest, North Carolina

The class below mine in school had a student who was eidetic and never forgot anything they read. In one class, the professor did not return exams to prevent the ubiquitous exam files that were routinely passed around, containing hundreds of old exams.

So the eidetic student altruistically made a study packet that included all the exam questions remembered and gave it to everybody in the class. This got back to the dean, who stopped the class at the end of a particularly well-attended day and proceeded to call them all unethical, unprofessional and dishonest.

This is funny for two reasons: 1) Between the First Amendment and neurobiology, it was apparent to almost everyone that you can't stop someone from memorizing something, nor can you ban study groups because some students have perfect memories. 2) That class was young and quiet. My class, however, had quite a few members over age 35, including a technician with 20 years of experience and a licensed attorney. If that had been tried with us, I could have guaranteed a lawsuit.

Unprofessional and unethical are important concepts, but I find that they usually mean, "It's not against the law or the rules, but I just don't like it."

Dr. Gregory C. Griffeth

Rochester, New York

Having taken the NAVLE in 2019, I remember thinking this test was a bit of a stretch on showcasing my clinical knowledge. Perhaps that was just the questions I had on seahorse medicine. But I am in agreement that it is a necessary evil. It shows that the person taking it can utilize the knowledge they've acquired and have prepared for and dealt with a very high-stress situation.

Dr. Jeremy George

Inlet Beach, Florida

I had a similar experience when I took the NAVLE in 2011, before graduating in 2012. After answering what seemed to be too many questions about gorillas, the shine of whatever it was supposed to be was pretty much gone for me.

I signed up to take the exam as early as possible because I didn't want studying for it to get in the way of my clinical experience at school. However, I made the mistake of not visiting the testing center before my test date, and when I put the address into Apple Maps, it took me to an empty strip mall. By the time I found it, I was 45 minutes late. I talked the one person there into letting me start, skipped the break and afterward, promptly forgot the rest of the test other than the multiple gorilla questions.

I passed and never used Apple Maps again. The whole thing was like being in a car wreck — unnecessarily traumatic and oddly forgettable at the same time.

Dr. Tony Bartels

Denver, Colorado

The NAVLE probably doesn't rise to the level of nuttiness that was once the New York state licensing exam. The exam was composed, administered and overseen by private practitioners from across the state — hardly a population of the most up-to-date and informed veterinarians. While I'm sure they and the state education department thought this would result in a truly practical test of real-world knowledge, it meant that examiners were able to foist their own, often wrong, opinions on the material that examinees faced. Examples I can vividly recall from more than 40 years ago include a ventrodorsal radiograph of a skeletally immature puppy with open growth plates, with the question "Diagnosis?" I wrote "normal." Later in the exam, while chatting with one of the examiners on another question, he asked me how things were going. I told him, "Not sure." He then asked, "Well, I hope you at least got the X-ray of the puppy with all the pelvic fractures!"

Dr. Jim Fingeroth

Orchard Park, New York