Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

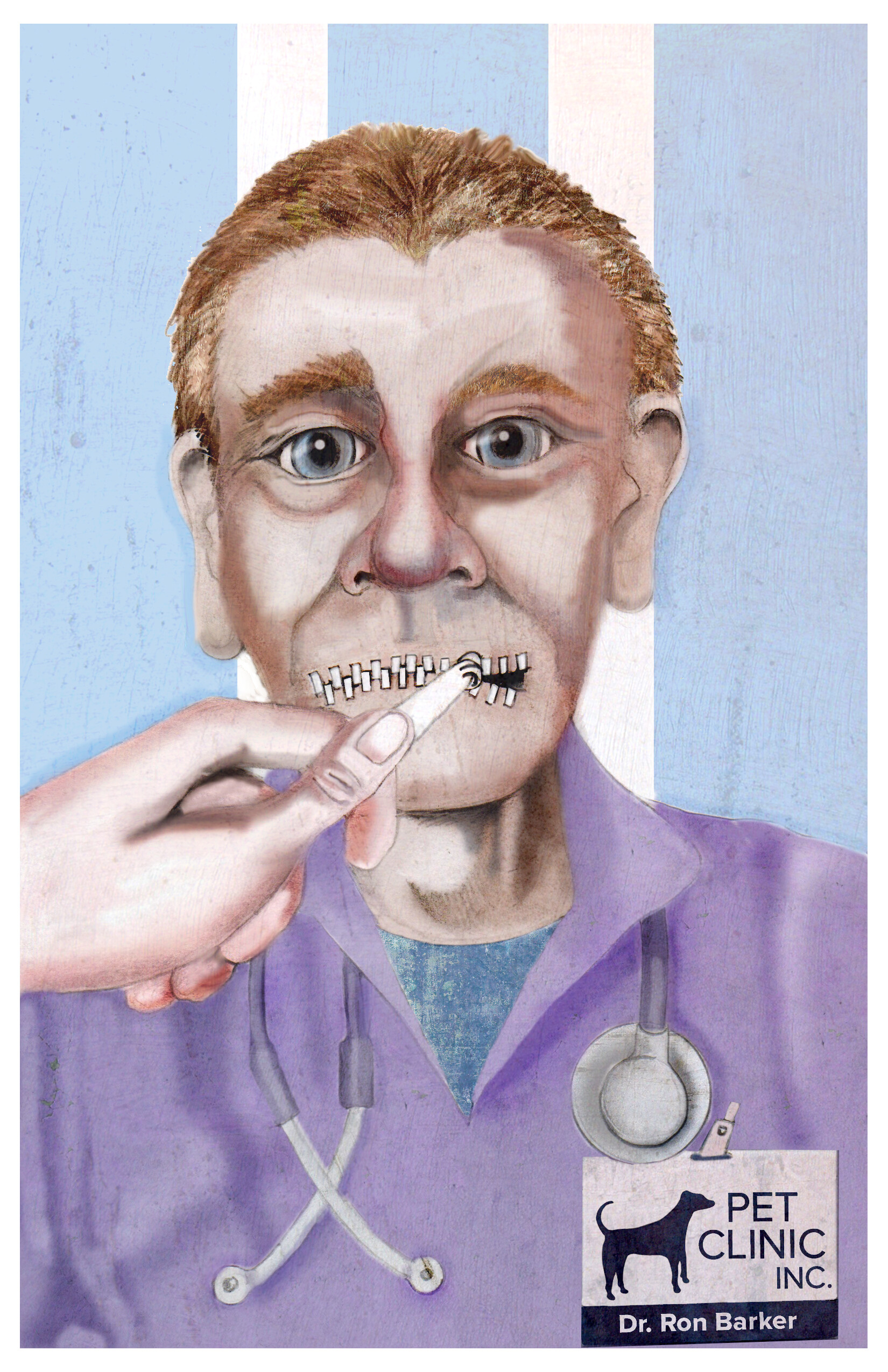

Unzipping

Illustration by Jon Williams

Many workers in the United States who have signed gag agreements that prevent them from criticizing employers have been given leeway to speak more freely, thanks to a pivotal legal decision.

Uncertainty remains, however, as to how many veterinarians have been unshackled from such gag clauses and exactly what they might now be allowed to say — partly because leeway apparently has been granted only to employees in "non-supervisory" roles.

So-called non-disparagement clauses can be found in various types of contracts, such as employment, severance, practice-sale and partnership agreements. They are designed to prevent the signer from saying negative things about their employer or practice buyer, even statements of truth.

Used for years in various industries, the clauses are appearing more regularly in a veterinary profession that recently started attracting substantial investments from large corporations, including private equity firms.

The VIN News Service has heard from two veterinarians who felt pressured into signing employment contracts with non-disparagement clauses that lasted for their entire lives, even should they leave their respective employers. Other practitioners said they'd encountered non-disparagement clauses with expiry dates, say, of five years.

The legal ground appears to be shifting, though, following a recent landmark decision by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), a federal agency that protects workers' rights to communicate with each other to improve their pay and working conditions.

The decision, handed down Feb. 21, centered on language that McLaren Macomb, a medical teaching hospital in Michigan, used in severance contracts for 11 employees laid off during the Covid-19 pandemic. The non-disparagement clauses in the contracts were unlawful, the NLRB ruled, because they prevented the employees from openly communicating — a protection spelled out in Section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act.

Subsequently, on March 22, NLRB General Counsel Jennifer A. Abruzzo issued guidance indicating that the McLaren Macomb decision implies American workers who have signed gagging clauses can speak more freely, including to third parties such as media outlets.

She confirmed the NLRB's interpretation of the law applied retrospectively, meaning that "overly broad" non-disparagement clauses in severance agreements signed before its ruling on Feb. 21 could be considered unlawful. And although the ruling specifically applied to severance agreements, she suggested the reasoning behind the ruling could be applied to employment agreements, too.

Specifically, Abruzzo said demands in "any employer communication to employees" that tend to interfere with their ability to speak openly would be unlawful "if not narrowly tailored to address a special circumstance justifying the impingement on workers' rights."

Abruzzo didn't elaborate on what kind of "narrowly tailored" provisions might be allowed. Elsewhere in her memo, she said non-disparagement clauses may be lawful if they are "narrowly tailored," "justified," and "meet the definition of defamation as being maliciously untrue."

So, does that mean veterinarians who have signed non-disparagement agreements may now say whatever they want — so long as it's not maliciously untrue? Not necessarily, lawyers caution.

'Supervisory' employees 'generally not protected'

One big caveat is that Section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act applies to employees in "non-supervisory" roles. Put simply, that indicates employees who manage or direct other employees aren't protected. The act defines supervisors as individuals with authority to hire, transfer, suspend, lay off, promote, assign, reward or discipline other employees; or to direct them in activities that are not merely "routine or clerical," but "require the use of independent thought."

Rick Warren, an attorney in Atlanta who specializes in labor law, said in an interview: "I would think most veterinarians are going to be either supervisors or managerial employees at a vet clinic. They are going to be in charge, or they're going to be a supervisor over the clinic staff, so the protections of this law would not apply to them."

Warren said he has advised small medical clinics where he'd consider doctors to be "supervisory" employees because they direct support staff such as nurses and medical assistants. Similar reasoning, he suggested, could apply in veterinary medicine regarding supervision of veterinary technicians and veterinary assistants.

Still, Warren said it's possible that certain junior or rank-and-file veterinarians, perhaps in hospitals with multiple staff, could be considered to be non-supervisory employees.

In her guidance memo, NLRB General Counsel Abruzzo stated that while supervisors are "generally not protected" under the National Labor Relations Act, the law does protect a supervisor from being "retaliated against" if they refuse to act on their employer's behalf in committing unfair labor practices against employees.

Despite that sliver of additional nuance, Dr. Lance Roasa, an attorney and veterinarian, agrees with Warren that supervisors are unlikely to be protected.

"Employers will argue that most veterinarians have the ability to direct employees and are, therefore, supervisors," he said on a message board of the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of the VIN News Service. "The act definitely does not apply to independent contractors or sellers of businesses," he added.

Roasa also is wary of ambiguity surrounding the "narrowly tailored" provisions that may still be allowed in non-disparagement clauses. "Lawyers are good at trying stuff until a court agrees," he said, meaning trying new language. "I think we can expect to continue to see [non-disparagement clauses] in professional employment agreements until the NLRB determines what is allowed under the 'narrowly tailored' language and whether the professional employees are included."

Contracts for practice sales, Warren agreed, likely aren't covered by February's NLRB ruling, since such contracts by themselves don't pertain to an employee's relationship with an employer. That's understandable, Warren said, given that corporations that pay what often amounts to millions of dollars for businesses are acquiring the goodwill of the business, too.

As for employment contracts, Warren, like Roasa, said what's allowed and what's not remains unclear. "This stuff is going to have to be worked out in specific cases — either cases by the NLRB or cases that get to court — to get sufficient guidance as to what the outer limits of this are," Warren said.

In the meantime, he said, some of his clients are erring on the safe side and toning down non-disparagement language in employment contracts.

"At least on a go-forward basis, employers are going to be more conservative and, for people they suspect this law would apply to, they're going to revise their non-disparagement provisions to something that says you may not make a maliciously false or defamatory statement about the company, its products, its services and its employees."