The coronaviruses that cause the potent respiratory diseases SARS, MERS and COVID-19 have an important feature in common: They are zoonotic, meaning they first came from animals. What does that mean for people and their pets?

Since February, four household pets have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus sweeping the globe: two dogs in Hong Kong, a Pomeranian and a German shepherd; a cat in Belgium; and, most recently, a cat in Hong Kong. All the animals' owners had COVID-19. Although they apparently picked up viral particles shed by their human companions, none of the Hong Kong pets showed signs of illness consistent with COVID-19. The Belgian cat, however, did become sick, showing signs about a week after its owner became ill.

The occurrences raise questions about whether pets could become part of the COVID-19 transmission chain. Veterinarians and other health experts say there is no cause for owners to abandon their animals for fear of catching the disease — if anything, it's the pets who should be kicking us out.

There is no evidence that pets can transmit the virus back to people. "I think it's far more likely that they'll get it from the person that's shedding large amounts of virus, rather than the other way around," said Dr. Melissa Kennedy, a virologist at the University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine.

Medical experts say the real threat lies in human-to-human transmission. While some pet species may be able to pick up infections, that doesn't mean they play a role in spreading the virus. Still, research is ongoing, and owners should include their pets when practicing COVID-19 precautions.

In his blog Worms & Germs, Dr. J. Scott Weese, a pathobiologist and internal medicine specialist at the University of Guelph's Ontario Veterinary College, advises: "If you're sick, stay away from animals just like you would other people. If you have COVID-19 and have been around your pets, keep your pets inside and away from other people. While the risk of transmission to or from a pet is low, we don't want an exposed pet tracking this virus out of the household (just like we don't want an infected person doing that)."

Meet the coronavirus family

Coronaviruses are diverse. They have adapted to occupy a slew of animal species, including birds, cats, dogs, pigs, mice, horses, whales, monkeys, ferrets, camels and cows. There are hundreds of known coronaviruses, which fall into four genetically different genera, or subgroups: alpha and beta, which mainly infect mammals; and gamma and delta, which mainly infect birds. Often, they don't make their host sick, and most cannot transmit from one species to another. But occasionally, when a virus evolves a mutation that benefits its ability to thrive, it can jump species, or "spill over." If the mutated virus can replicate to high enough levels, it can cause an outbreak among humans or other animals.

Seven known coronaviruses infect people. Four of these are endemic — that is, regularly found in a particular region — and usually cause what we call a common cold.

Three of the seven coronaviruses that afflict humans have evolved within the past two decades and can make some people severely ill. These are SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and, most recently, SARS-CoV-2.

All three are thought to have come from bats, whose specially adapted immune systems enable them to carry coronaviruses without becoming sick. The coronavirus that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2002 may have passed directly from bats, but is thought to have been transmitted to humans largely through intermediate animals — likely masked palm civets and raccoon dogs, both common in Chinese live-animal markets. The coronavirus that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome exists comfortably in dromedary camels without causing them obvious signs of illness. To this day, camels occasionally pass the virus to the humans who handle them. Experts suspect that SARS-CoV-2, the cause of COVID-19, also may have made the journey from bats to humans through an unknown intermediate animal, perhaps the pangolin.

What makes the SARS and MERS viruses special? How can they transmit to humans when other members of their family cannot?

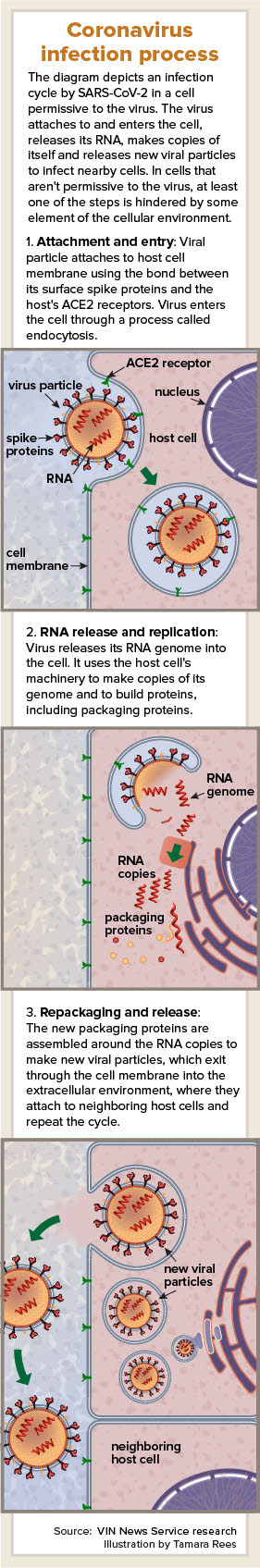

The answer lies in the name. The coronavirus is named for the crown, or corona, of spikes on its surface, which the virus uses to attach to the outside of host cells and insert its RNA. These spike proteins have binding sites that stick to a specific cell receptor protein on the host cell's surface. Many viruses recognize only receptors that are specific to one animal species.

Others are generalists. A recent study in the Journal of Virology found that the spikes of both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 bind to a host cell receptor called angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, or ACE2. ACE2 is found in many different animals, and if the spike protein can form a strong enough bond with an animal's ACE2, the virus can successfully infect that animal's cells. According to the study authors, the SARS virus evolved mutations in its spike protein to better stick to human ACE2 during the 2002 epidemic.

The researchers found that SARS-CoV-2 spikes also appear to bind well to ACE2 — and not just in humans but also in other primates, bats, pigs, ferrets and cats. Other studies have suggested that it also recognizes ACE2 in pangolins, civets, raccoon dogs, camels and, possibly, domestic dogs.

The veterinary and research communities remain vigilant. But although domestic animals such as cats and dogs may be infected, viral transmission in household pets is considered unlikely. Based on current evidence, Kennedy believes that dogs are not "epidemiologically important" for COVID-19. That's because there's more to a successful infection than sticking to host cells. And while humans provide a very comfortable environment for SARS-CoV-2, Kennedy said, dogs apparently do not.

'Infected' versus 'infectious'

The dogs that tested positive in Hong Kong were found to have viral RNA in the mouth and nose. When the Hong Kong Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department performed serological tests to measure antibodies against COVID-19 in the blood of the Pomeranian, the final result came back positive, indicating a bona fide infection. However, the dog never showed any clinical signs.

In fact, you can be infected with a virus without feeling sick. When you feel ill, it's the result of the virus replicating to high enough levels to do two things: first, to destroy large numbers of healthy cells; and second, to trigger inflammation that can cause unpleasant symptoms such as fever and coughing. But if the virus can't replicate efficiently, it can't muster enough copies of itself to pose much of a challenge to the body's immune system, which mounts a coordinated attack and clears out the invader before its host notices symptoms.

It seems likely, Kennedy said, that dogs are not a hospitable host for SARS-CoV-2. "The host specificity of a virus is determined, basically, by two factors," she explained: "One, that the cells the virus is infecting have a receptor that it can attach to. And then, once the virus is inside the cell, that cell has to be able to provide everything that the virus needs in order to replicate."

While dogs' cells might have a fitting ACE2 receptor, Kennedy suspects that SARS-CoV-2 isn't happy enough in the canine cellular environment to replicate to high levels. There must also be a large enough dose of virus to breach the frontline defenses of every new host. Without the ability to replicate efficiently, the virus has nowhere to go.

Vaccinating against coronavirus

| Alphacoronaviruses |

Host |

| Canine enteric coronavirus (CCoV) |

Dog |

| Feline coronavirus (FCoV) |

Cat |

| Porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) |

Pig |

| Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) |

Pig |

| Ferret enteric coronavirus (FRECV) |

Ferret |

| Ferret systemic coronavirus (FRSCV) |

Ferret |

| Mink coronavirus (MCoV) |

Mink |

| Betacoronaviruses |

|

| Bovine coronavirus (BCoV) |

Cow |

| Canine respiratory coronavirus (CRCoV) |

Dog |

| Equine coronavirus (ECoV) |

Horse |

| Porcine hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus (PHEV) |

Pig |

| Deltacoronaviruses |

|

| Porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) |

Pig |

In humans, there's no doubt: Our bodies are like a five-star hotel for SARS-CoV-2. We can transmit the disease even without symptoms, perhaps because our cells are quite permissive to the virus. This effect is amplified in cities, where the high density of people means that a large population is being exposed to particularly high levels of virus.

As for dogs, Kennedy believes they are likely a dead end for SARS-CoV-2 — meaning they can catch the virus but they cannot give it back. While human cells are permissive for some reason, canine cells may not be. "From what we know thus far, the dog is not providing everything that virus needs in order to replicate to significant enough levels to make it important in the spread of the virus," she said. "There may not be enough permissive cells. But that's under investigation now."

The cells of cats and ferrets, however, appear to be more receptive to coronaviruses. Scientists at Harbin Veterinary Research Institute in China, in a study not yet peer reviewed, found that "SARS-CoV-2 replicates poorly in dogs, pigs, chickens and ducks, but efficiently in ferrets and cats. We found that the virus transmits in cats via respiratory droplets."

The finding on cats and ferrets is consistent with the SARS virus from 2002. For that reason, Weese, who is a zoonotic disease expert at Ontario Veterinary College, anticipated some weeks ago that cats and ferrets might become infected by the virus that causes COVID-19. "With the original SARS virus, cats ... were able to grow enough virus to pass it on to another cat," he said.

Weese was therefore unsurprised by the news about the Belgian cat, which had both a positive test result and clinical signs. According to an article in The Brussels Times, the cat had diarrhea, vomiting and difficulty breathing. Researchers found virus in the cat's feces, the newspaper reported. The cat in Hong Kong, which has not shown any signs of the disease, also had virus in its rectal samples, as well as in its mouth and nose, according to the government statement.

Ferrets, too, have been found to have ACE2 receptors and are permissive to a number of viruses that infect humans, including some types of bird flu and seasonal flu, according to Kennedy. Early studies have shown that SARS-CoV-2 replicates well in ferret cells. However, Weese believes their transmission risks are low, at least from an epidemiological standpoint.

"If you put a cat and a ferret in front of me and ask me which one I want to get in close contact with, I'd pick the cat, because ferrets are high risk at that one-on-one level," he said. "But for me, cats are still a bigger concern because there are a lot more cats than ferrets."

While the susceptibility of ferrets may be worrisome for ferret owners, it could be a boon for COVID-19 research. According to the New York Times, scientists at the University of Pittsburgh recently found that a ferret in their lab developed a high fever after being exposed to SARS-CoV-2. The strong immune response suggests ferrets likely are vulnerable to illness, which makes them a promising animal model for developing a COVID-19 vaccine.

Assessing risk

Despite the ferret finding, experts believe the likelihood of catching COVID-19 from a pet ferret or cat is low. Even if transmission to individual owners is theoretically possible, both Weese and Kennedy believe the risk does not translate to large-scale spread.

"An infected cat isn't a big concern in the household, since the person who exposed the cat in the first place is the main risk," Weese wrote last week in his blog. "The virus is being transmitted very effectively person to person, so animals likely play little role, if any, in the grand scheme of things."

Other than the Belgian cat, there are no other reports of domestic animals, including livestock, getting sick with COVID-19. That could change, of course; more animals from households with COVID-19 cases need to be tested to form a clearer picture.

Furthermore, viruses are apt to mutate, and coronaviruses have unusually large genomes, predisposing them to a large number of mutations. Such genetic "mistakes" are what drive their evolution. "Those mistakes are purely random," Kennedy explained, "but if they give that virus selective advantage over its comrades, then that mutation will be maintained in the virus population."

If SARS-CoV-2 were to mutate such that the virus became more able to infect and spread, domestic animals could become reservoirs. That would have major implications for a world full of pet and livestock owners. It's also theoretically possible the virus could find a way to spill over from cats or ferrets back into humans. But there's no evidence to date that this is happening.

A call for common sense

Weese is working on testing more animals from COVID-19-positive households. "We're trying to do active surveillance of animals that are in contact with infected people," he said.

If many more positive tests emerge in pets, public-health experts will review the transmission risks. But routinely testing large populations of domestic animals would be impractical and probably not very informative, Weese said: "Testing is useful to use from a research standpoint, but testing your average animal isn't something we want to get done."

His focus is on practical protective measures. For pig farmers, for example, simply exercising caution may effectively prevent transmission. "If you've got COVID and you've got pigs but you don't go near the barn, then we don't have to worry about it," Weese said. "And with farmers, it's actually probably easier [than with pet owners], because a pig farmer realizes that if someone reports a pig being positive, pork prices are going to plummet."

For pet owners, it's about managing animals the same way we manage people, Weese said. This means staying separated from pets if you're sick, as painful as it may be to deny yourself snuggle therapy. It also means including pets in social distancing. If you are under local stay-at-home orders and keeping a distance from others, keep your pet distant from others, too. Even if pets can't get COVID-19, viral particles can get on their mouth, nose, fur or skin and be picked up by the next person who touches them. Think of pets as another surface that can be contaminated, like a countertop or door handle. The overall message, Weese said, is simple: "Just use common sense."

The best defense against transmission by household pets is to keep exposed animals in the home but sometimes this is impossible; for instance, if someone who lives alone needs to be hospitalized. In a blog post Thursday, Weese discusses options for such situations. The best scenario, he writes, is for someone who has recovered from COVID-19 to come into the household to continue caring for the pet. If no one is available, not even a benevolent low-risk neighbor, owners may be able to temporarily house their pet with a shelter or clinic that has the facilities and capacity. Weese's own hospital is positioned to house animals from COVID-19 households. Space is limited, and the option is intended as a last resort. "We're set up to handle those animals," he said, "but our focus is to keep animals in the household or find alternative approaches rather than see them in clinics."

Corrections: This story has been changed from the original to remove a repetitive passage. The article also has been changed to remove an incorrect statement about coronavirus genetic replication and proofreading enzymes. The latest research suggests some coronaviruses do possess a proofreading enzyme.