Anne E. Katherman, DVM, DACVIM (Neurology)

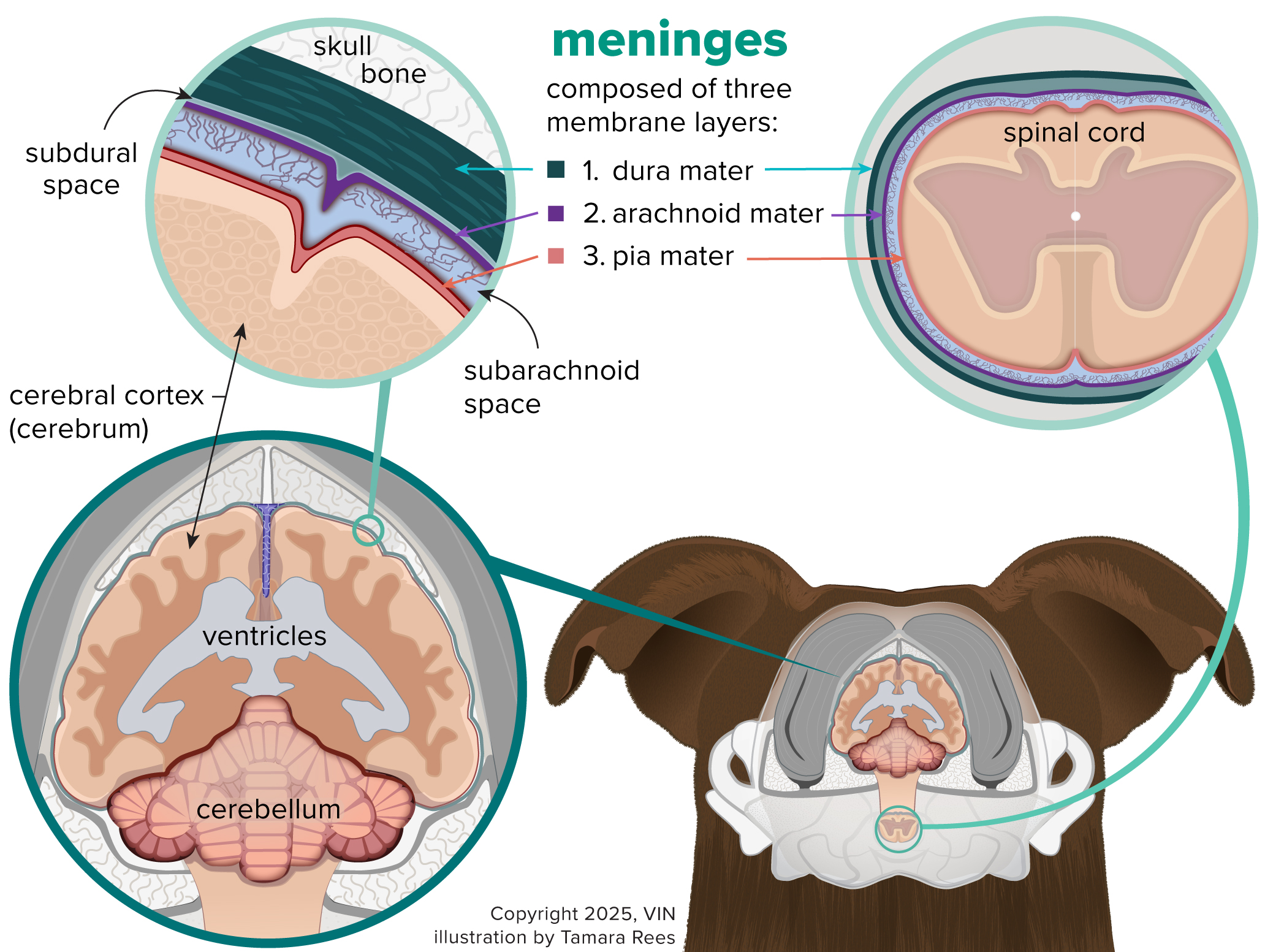

Brain, Meninges & Spinal Cord

Meningoencephalitis is an inflammation involving the brain. A diagnosis of Meningoencephalitis of Unknown Origin (MUO) means the reason for the condition is not known. The current understanding is that MUO is an immune-mediated (related to the immune system) disease that involves white blood cells called T-lymphocytes sending inappropriate signals, causing an immune attack against the patient's nervous system. Veterinarians don't know yet where these cells arise from.

Subcategories of MUO/MUE:

- Granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis (GME)

- Necrotizing Meningoencephalitis (NME)

- Necrotizing leukoencephalitis (NLE)

The different types are identified based on differences in the appearance of cells under a microscope and the location of abnormal or damaged tissue.

When scientists studied the brains of dogs with this condition, they found pathological changes that matched all three types (GME, NME, and NLE). This suggests that different forms of the same disease might exist.

GME:

There are three types of GME: focal (limited to one location in the nervous system), disseminated or multifocal (involving many locations in the nervous system), and ocular (involving the optic nerve/eye). A patient may have more than one type. The disseminated form is the most common.

Important Terms:

- Meningoencephalitis: an inflammation involving the brain and the meninges, the tissues surrounding the brain.

- Meningoencephalomyelitis: an inflammation involving the brain, the meninges, and the spinal cord.

- Meningoencephalitis and meningoencephalomyelitis can be caused by infections (viral, bacterial, fungal, or protozoal) or can be a sterile, non-infectious, inflammatory disease that involves an abnormal immune system attack on the normal brain and/or spinal cord.

- Immune-mediated disease: sterile, non-infectious

- Unknown Origin: The cause of the disease is unable to be determined; idiopathic

- Meningoencephalitis of Unknown Origin/(MUO/MUE). When the immune system malfunctions and attacks its own healthy tissues, this is called an immune-mediated disease. The causes of immune-mediated meningoencephalitis and meningoencephalomyelitis are unknown, although genetic predisposition and abnormal immune system stimulation are thought to play a major role.

Signs of MUO

The condition is seen typically in young to middle-aged small-breed dogs, but it can affect dogs of any breed or age. The type of neurologic signs depends entirely on the part of the nervous system that is affected. Clinical signs may include:

- seizures

- depression

- altered mentation (ability to think and act)

- gait abnormalities

- abnormalities in the function of nerves of the eyes and face

- head tilt and balance problems

- circling

- problems with coordination

- visual problems

- neck pain

- partial or complete paralysis of one or more limbs.

Blindness, pupils of different sizes, abnormal pupillary light responses, inflammation of the back of the eye, and swelling of the optic disk can also be seen. Clinical signs indicative of abnormalities outside the nervous system (e.g., fever) are rare.

Making the Diagnosis

Your veterinarian will consider your dog’s age, breed, and signs, along with the interpretation of the test results for infectious diseases, to make a diagnosis.

Microscopic evaluation of the brain and spinal cord via brain biopsy or necropsy is needed to confirm a diagnosis.

For patients with brain-related signs, a physical examination and complete neurological examination, along with a basic blood panel and urinalysis, are needed to know your dog’s general health and define the neurologic disease.

Your veterinarian may recommend tests for common infectious diseases of the nervous system and referral to a specialist (neurologist) for evaluation, MRI, and cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) can image the brain in such detail that it is considered nearly a confirmatory test for MUO. Recent studies have also shown a correlation between specific MRI findings and prognosis for 12-month survival and risk of relapse. A CT (CAT scan) is not as definitive. MRI can also determine if there is a significant risk in performing a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tap.

- A CSF tap, also known as a spinal tap, involves collecting a sample of cerebrospinal fluid to examine the types of cells it contains. This test can help your veterinarian diagnose infectious organisms, cancer cells, or inflammatory cells that may be present with other diseases of the nervous system.

Your dog will need to be under general anesthesia for these procedures, and your veterinarian will discuss the potential benefits and risks with you beforehand.

It's crucial to rule out an infection before starting treatment because steroids, the primary treatment for MUO, suppress the immune system, making it harder to fight off infections in the central nervous system.

Treatment

Immune Suppression and Chemotherapy

Treating MUO usually involves using medications called corticosteroids, such as prednisolone, to suppress the immune system. These steroids are the main part of the treatment. Once the disease is under control, the dose of steroids is slowly reduced until your veterinarian finds the lowest amount needed to keep your dog’s disease in check. This process can take about four months, and sometimes, the disease comes back during this time. Not all dogs respond the same way to steroids, and using them for a long time can cause some unwanted side effects.

Multiple chemotherapeutic medications have been combined with corticosteroids to help improve outcomes and allow the dose of corticosteroids to be gradually lowered.

Some of the more common chemotherapeutic agents used include:

- cytosar arabinoside,

- cyclosporin,

- procarbazine,

- azathioprine

- mycophenolate mofetil, and

- leflunomide.

Recent studies have shown no difference in survival rates between different combinations of chemotherapeutic medications plus corticosteroids and corticosteroids alone. Various protocols are used, but the best treatment for MUO is still unknown.

Clinician choice as well as factors including ease of frequent travel for treatment and monitoring, availability of hospitals capable of administering the chosen drug safely, temperament of the dog and ease of vascular access (heart, blood, and blood vessels), financial considerations and associated medical conditions affecting you or your dog all play important roles in determining treatment and protocol.

Dogs treated with immunosuppressant agents, including corticosteroids and chemotherapeutic agents, are more likely to develop infectious diseases, so it is recommended that they avoid situations where multiple dogs are present, such as doggy daycare, dog parks, and boarding.

Safe handling of chemotherapeutic agents and an understanding of conception and pregnancy risks associated with drugs prescribed for home administration is important.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is a type of cancer treatment that uses high-energy radiation to destroy cancer cells. Your veterinarian might suggest this for MUO if it is only in one spot. This treatment can work well, but it also has some serious side effects, like unusual blood clotting and seizures. Seizures might happen for up to six months after the therapy. Less serious side effects include dry eyes and cataracts.

Anti-seizure Medications

If generalized or focal seizures have been a manifestation of MUO, anti-seizure medication may be used to control them. The choice of anti-seizure medication is based on patient and owner factors and is not specific to any disease.

Prognosis

In a study of 447 dogs with MUO, dogs were given a worse prognosis if epileptic seizures, partial or complete paralysis, and a higher degree of general neurologic disability were present.

The incomplete resolution of clinical signs six months after diagnosis, a higher degree of neurologic disability, and a longer duration of clinical signs were associated with chances of relapse.

In another study of 138 dogs, younger age and diagnosis within seven days of the onset of clinical signs were related to a better prognosis.

Dogs with the disseminated form have a poor prognosis, with average survival times in untreated dogs ranging from eight days to 30 days from the time of diagnosis, depending on the study. Regardless of the form, MUO is not curable, and life-long medication is necessary.