Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

Bunsen before surgery

Photo courtesy of Jason Zackowski

Bunsen, a Bernese mountain dog living in Alberta, Canada, appeared uncomfortable and in pain before surgery to remove a mysterious mass in his abdomen in August. His owners Kris (pictured) and Jason Zackowski — along with legions of Instagram followers — worried he might not survive the surgery.

Until he was 7 years old, Bunsen lived a carefree life. The Bernese mountain dog romped on a farm in Alberta, Canada — his adventures with two dog buddies and a cat named Ginger followed by hundreds of thousands of users on X, Instagram and other social media platforms.

But on the morning of Aug. 16, Bunsen was in distress. He vomited continuously, his belly looked swollen and he appeared to be in pain.

As his owners, Kris and Jason Zackowski, raced their dog to the emergency hospital in the nearby city of Red Deer, they feared he was suffering from a common and life-threatening condition informally called bloat. Little did they know, something very different was going on in Bunsen's abdomen.

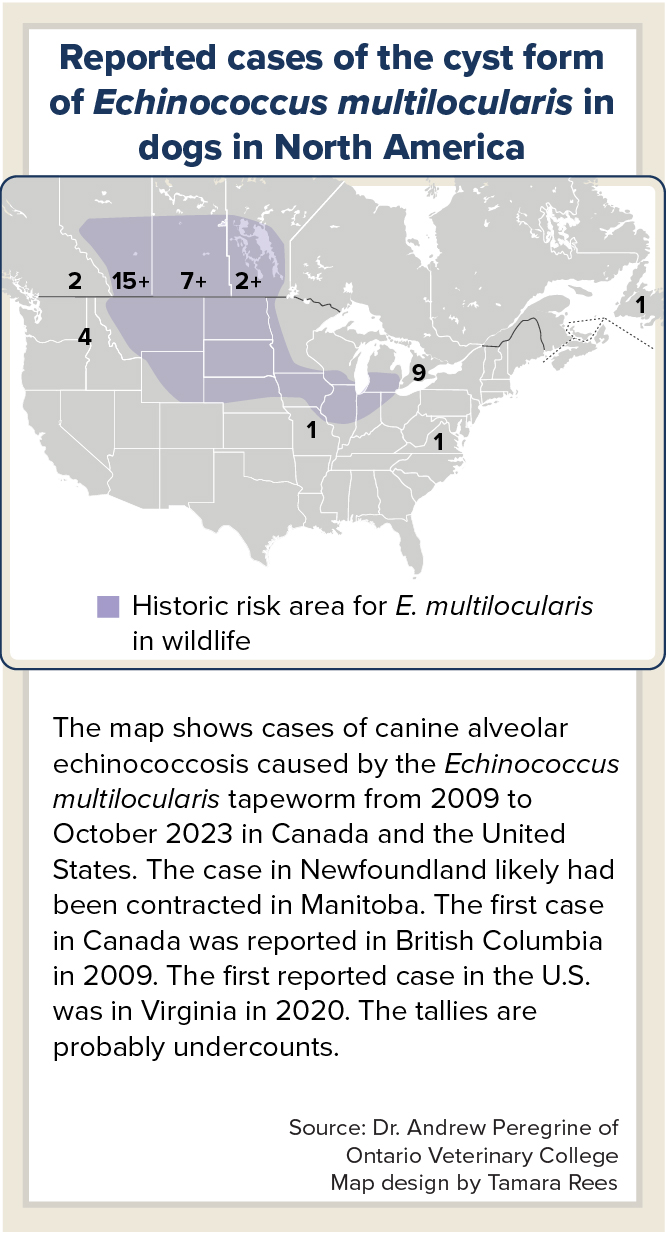

It would take weeks to discover the cause of his troubles: a disease called alveolar echinococcosis, or AE for short, that's caused by a tapeworm. The disease defies easy diagnosis and has so far been reported in fewer than 50 dogs in North America.

While Bunsen's case was a first to those involved in his care, some infectious disease specialists and veterinary parasitologists in Canada and the United States have been clued in for years to the slow but steady increase in AE cases — and the expanding range of the Echinococcus multilocularis tapeworm that causes the disease.

Echinococcus is a genus of zoonotic tapeworms, one of three main groups of tapeworms around the world.

In recent published papers, many out of Canadian veterinary schools, researchers have highlighted this emerging infectious disease as it is being identified in novel areas. They also have stressed the need for expanded awareness and vigilance at the clinic level, including fecal screening and judicious deworming treatment of dogs.

Mystery in the ER

When Bunsen arrived at Cedarwood Veterinary Animal and Emergency Hospital in Red Deer, it seemed most likely his problem was gastric dilation-volvulus syndrome (GDV). The life-threatening condition occurs when a dog's stomach twists and fills with gas, food or fluid. GDV disproportionately affects large dogs like Bunsen and often requires emergency surgery.

"We pretty much dropped everything else that we were doing at that time," said Dr. Graham Keys, a veterinary surgeon, who was brought in to review Bunsen's X-rays. "If it was a GDV … it would be all hands on deck to make sure that we were taking care of him."

The X-rays showed a spherical-looking soft tissue "density" in the stomach area. To rule out GDV, Keys inserted a tube through the dog's mouth and into his stomach to retrieve fluid. He expected several liters. "We got none," he said. "I was a little surprised by that."

With GDV seeming less likely, Keys ordered an abdominal ultrasound that was observed by a growing group of curious colleagues. It revealed a large, fluid-filled structure with a thick wall displacing the rest of Bunsen's abdominal organs.

The doctor phoned one of Bunsen's owners, Jason Zackowski. "I have no idea what this is," Keys recalled telling him. "It doesn't strike me as a mass … and it doesn't strike me as a tumor." He settled on the nonspecific term "cyst" without a diagnosis and suggested surgical exploration and hopefully removal of the mass.

He warned that it could be inoperable cancer or that Bunsen could die in surgery.

"It was super scary, and we were not ready to say goodbye to him," Zackowski, a high school chemistry teacher, told the VIN News Service. Nor was the dog's social media following ready. "Literally hundreds of thousands of people were waiting on the surgery," Zackowski explained. "Bunsen was trending on Twitter ahead of most major news that day."

Keys did an exploratory laparotomy, a surgery that entails an incision in the abdominal cavity. A "very brave veterinary student" held the cyst while the surgeon worked. "I had to do my best to tie it off, blindly, working underneath it," Keys said. "I never really got a good look as to where the blood supply was coming from other than it was coming from the same blood supply as the liver."

He removed two masses. The smaller of the two was later diagnosed as a benign tumor. "The star of the show was that 20-centimeter, highly vascularized spherical object, which was full of fluid and looked horrifying," Keys said, adding that he'd never seen a cyst of this size in a dog.

He emptied it into the sink, retaining some of the fluid for analysis. Then he preserved the shell of the cyst in formalin and sent it to a veterinary pathologist at the University of Calgary.

Bunsen was home the next day.

Around the time of the patient's two-week recheck, Keys got a call from Dr. Jennifer Davies at the University of Calgary veterinary pathology department. "In a very serious tone, she described to me what she was seeing [and] what her suspicions were, that this was a tapeworm [cyst]" caused by the E. multilocularis tapeworm, Keys said.

Bunsen's cyst

Cedarwood Veterinary Animal and Emergency Hospital photo

In August, Dr. Graham Keys removed two masses from Bunsen's abdomen. The small one was a benign tumor. The large one was a 20-centimeter tapeworm cyst. Keys later described lifting it out as requiring "more strength than skill."

Those suspicions were later confirmed with two PCR tests. PCR stands for polymerase chain reaction, a technique that amplifies a small sample of genetic material to study it.

Keys recommended that Bunsen's family screen the other dogs in the household for the tapeworm and treat with dewormers as recommended by their regular veterinarian. He also suggested they consider getting a CT scan in several weeks or months to rule out further cysts in Bunsen's abdomen and thorax. In addition, Keys encouraged the Zackowskis to visit their own doctors to assess any risk of exposure to the parasite.

Nearly four months later, Bunsen seems well. Zackowski said recently that the dog is "running around on adventures like it never happened."

Accidental host

Understanding why Bunsen's case is unusual requires a dive into the typical life cycle of the E. multilocularis tapeworm. The parasite is generally transmitted between two different groups of wild animals, known as definitive hosts and intermediate hosts.

The definitive host usually is a canid, such as a coyote, fox or wolf. A canid acquires the tapeworm when it ingests an intermediate host, such as a vole, shrew, mouse or lemming, that harbors the larval stage of the parasite. When a canid ingests the rodent, the larvae can develop into adult tapeworms in the canid's intestine.

The tapeworm has a head with hooks and suckers that attach to the lining of a definitive host's intestines. The rest of its body is comprised of segments containing eggs that break off as the parasite grows and are shed in the animal's feces. This is known as an intestinal infection and, as bad as it sounds, doesn't appear to affect the health of the host.

E. multilocularis eggs have two qualities that make them formidable: They are immediately infective and can survive outside of a host's body for months.

If and when a rodent ingests tapeworm eggs that were shed in feces, it becomes infected as an intermediate host. The eggs travel through the rodent's intestines, hatch and release larvae that migrate through the wall of the intestinal tract into the bloodstream to a location in the host's body that's rich in blood supply, typically the liver. There, the tapeworm forms a cystic-like structure that invades neighboring tissue. The resulting disease is called AE — alveolar echinococcosis. This is also sometimes called the "cyst form" or "liver form" of E. multilocularis infection.

Chart_Map_rare_tapeworm

When a canid comes along and eats the rodent with the cysts, it becomes infected, and the cycle begins again.

Bunsen is what's known as an aberrant or accidental intermediate host, an animal that can develop AE but is not part of the normal life cycle. Hard as it is to picture, he's like a mouse in the E. multilocularis life cycle. The assumption is that Bunsen ingested poop containing large numbers of tapeworm eggs, most likely in the feces of a fox or coyote, and the tapeworm set up shop in his liver.

The species E. multilocularis is so named because it forms small cystic structures with loculi (cavities). It's highly unusual but not unprecedented for it to present as a single large cyst, as in Bunsen's case.

Humans can also be an accidental intermediate host and develop AE, but it's still quite rare, since most people are not ingesting eggs spread in the feces of infected wild canids or dogs.

In humans, tapeworm infections can take five to 15 years to incubate in the liver, so the disease is often far along when it is discovered. Untreated, AE is generally fatal in humans and dogs because it destroys much of the liver and potentially other organs to which it spreads. Treatment usually includes excising as much of the cyst as possible, followed by ongoing treatment with a dewormer.

Humans, including veterinary care teams, are not in danger of infection from exposure to E. multilocularis cysts. However, since some dogs with AE also have the intestinal infection, they may shed eggs in feces that could infect their human caregivers, although this mode of infection is probably pretty rare.

Expanding risk areas in North America

When Dr. Andrew Peregrine, a veterinary parasitologist at the University of Guelph's Ontario Veterinary College, moved to Ontario from East Africa in 1997, he was told he didn't need to worry about E. multilocularis because it wasn't in the province. The only North American cases had been in wildlife in the central provinces and in Alaska. As far as anyone knew, that remained true for the next decade or so.

Then, in 2009, Peregrine got a call from a veterinarian in British Columbia that would open a new chapter in the story. The veterinarian told Peregrine they had "something weird" in a dog. He recalled him saying, "We've removed a very large liver lesion. Everyone said it was obviously a tumor until it was put under a microscope."

The team in British Columbia sent Peregrine some of the dog's liver to look at under a microscope. What he and assisting pathologists saw was just like images he'd seen of AE in dogs in Switzerland. Up to that point, the only place the liver form of E. multilocularis infection had been described in dogs was in Central Europe, he said, adding that the Swiss have historically been considered the world experts on the subject. At the time, there was no diagnostic laboratory in North America that could test for the tapeworm, so tissue was sent to Switzerland, where the diagnosis was confirmed.

E. multilocularis is also present in the Arctic, China, northern Europe and Japan.

Two years later, Peregrine got a call about another dog with AE, this time in southern Ontario. Since then, five provinces have clocked at least 35 canine AE cases combined. (Three lemurs in a private Ontario petting zoo also died from AE.) All of the AE cases in Canada have occurred in the southern part of the provinces in which they were described.

Alberta is the epicenter. According to Peregrine, who has been tracking reports, the province has seen at least 15 known cases of canine AE as of 2023 and 26 cases of AE in humans between 2013 and 2023. In the rest of the country, six cases of AE in humans were reported between 2017 and 2022, one of which was travel-related.

The first case of canine AE in the U.S. was in Virginia in 2020. At least five more cases have been reported since then. Two cases in humans that appeared to be locally acquired were described in 2022, both in Vermont. Multiple human cases of AE (but no canine AE) were described before the 1980s in the northwestern coastal area of Alaska, where E. multilocularis has long been considered endemic.

The number of AE cases in dogs in both countries is probably an undercount, since Ontario appears to be the only North American jurisdiction that requires that E. multilocularis infection in dogs and humans be reported to authorities, according to Peregrine.

In addition, as the British Columbia case and Bunsen's illustrate, it can be hard to diagnose AE — especially for veterinarians who aren't looking for it. The mass can easily be dismissed as a tumor, which may lead to euthanasia or palliative care without further testing.

To veterinarians who live in or within a few 100 miles of areas where E. multilocularis is present in wildlife, Peregrine urges, "before you euthanize a dog with what looks like an obvious liver tumor, send some of the tissue to a pathologist just to confirm that. … It is likely that a lot of the dogs with liver disease are being missed."

A challenge may be knowing the local risk. High infection rates have been identified in wild canids in places like Ontario and Alberta, but limited surveillance has been performed elsewhere.

Bunsen_doing_great

Photo by Jason Zakowski

Jason Zackowski said his social media accounts featuring Bunsen, along with a golden retriever named Beaker and another Bernese mountain dog named Bernoulli, aim to "teach science concepts, uplift and be joyful [and] entertain." That Bunsen, seen this fall looking healthy, became a direct science lesson was not part of the plan.

Peregrine points out that testing has an important potential public health advantage.

"There's a benefit to that family because there's about a one-third chance that the dog also, at some point, had an intestinal infection," he said. The people in that household might have been exposed to eggs in the dog's feces. Because AE has a long incubation in humans, knowing there might have been exposure can help with early intervention, he explained.

Peregrine is concerned that many more cases of AE in humans may be on the horizon. "In new risk areas, a good number of human cases have not yet gone clinical because it takes so long," he said. "So, are we working with a ticking time bomb? I'm hoping I'm wrong, but that's what happened in Alberta. They're seeing an increasing number of human cases."

For decades, the recognized risk areas for E. multilocularis in wildlife encompassed the southern parts of central Canadian provinces and 13 states, mostly in the northern Midwest. Recent studies sampling wild canid feces in North America have found the tapeworm present in coyotes and foxes well outside these areas, including in British Columbia, Quebec and Ontario in Canada, and New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia in the U.S.

"As the tapeworm builds up in wildlife, it will almost certainly spread to dogs as intestinal infection" and pose a risk to human health, Peregrine said.

A review of PCR tests of dog fecal samples in North America from March 2022 to July 2024 found E. multilocularis in unexpected locations but also highlighted how truly rare it is in dogs.

Out of more than 2.3 million tests, 26 were positive for the tapeworm, according to the report published online in October in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. There were five positive tests in Alberta, four in Ontario and one in British Columbia. Eight were in the northwestern U.S., three in Illinois, two in Colorado, and one each in Kansas, Nevada and Wyoming. Most of these states traditionally have not been considered risk areas.

Life after AE

The recommended medication for dogs with AE is two dewormers. First, praziquantel is given to kill any possible tapeworms in the intestine. The feces of the affected dog and any other dogs in the household should be regularly tested for tapeworm and treated as necessary.

Secondly, albendazole is often prescribed daily and for life, according to Peregrine, who also coauthored the chapter on tapeworms in the reference book Greene's Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. Unlike praziquantel, albendazole is effective in controlling the cyst form of the disease. This is important because many times it is impossible to remove all of the cystic structure in the liver if it is too extensive.

"I would never say the prognosis is brilliant for any dog [with AE]," Peregrine said. "But if the dog can tolerate the albendazole treatment, there's a reasonable prognosis, dependent on the severity of pathology at the time of diagnosis. With the one caveat, there are a few dogs where it doesn't seem to control the infection long-term."

Peregrine also told of a case in which owners stopped giving the dog albendazole after four years on the drug. It died six months later. "Whilst dogs are on the drug, it stops the parasite growing," Peregrine said. "But it's like chemotherapy for tumors. If you stop, everything starts growing again."