Introduction

If your dog has been diagnosed with a torn cranial cruciate (knee) ligament, TPLO surgery may be recommended. TPLO stands for tibial (shin bone) plateau (upper surface of the shin bone; bottom of the knee joint) leveling (making the plateau more parallel to the ground) osteotomy (bone cutting procedure—like a controlled fracture of the bone).

Background

TPLO was first described in the early 1980s, and a great deal of research has been done since, both to refine the technique and hardware used, and to compare its results to other surgical procedures. It has withstood the test of time, and while still not considered the “perfect” surgery for CCL disease, it has emerged as the most reliable technique offered by veterinary orthopedic surgeons for the management of CCL disease (cranial cruciate ligament) in dogs.

Canine cranial cruciate ligament diagram

What is Cranial Cruciate Ligament Disease?

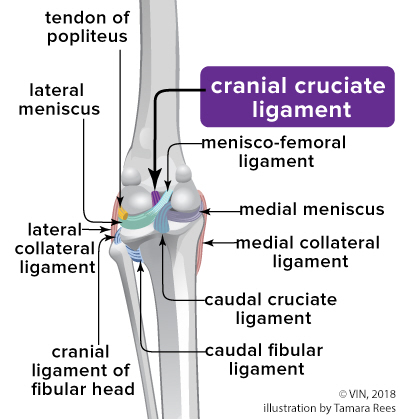

The knee joint or stifle connects the thigh to the lower leg. Inside the knee are cartilage plates (meniscus) and ligaments (cruciate ligaments). In dogs and cats, these ligaments are called cranial (CCL) and caudal (CaCL).

Cruciate ligament tears are the most commonly diagnosed orthopedic problem in dogs. Most ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) tears in humans result from sports-related trauma, but most cruciate tears in dogs result from a progressive degenerative process in the ligaments combined with normal activity, which is called cranial cruciate ligament disease, or CCL, in pets.

Affected dogs may show sudden signs of lameness even though the ligament has been failing for some time. This is usually due to either the final failure of a partially torn ligament and/or the addition of a meniscal tear. The exact cause of such degeneration is still poorly understood, but genes may play a role.

When the ACL/CCL is torn, there is an abnormal sliding motion between the thigh bone (femur) and tibia. This motion can be detected by performing a “drawer” test, where passive laxity (instability) can be felt when the patient isn’t bearing weight on the limb. When such sliding motion occurs during weight bearing, it is referred to as dynamic drawer/instability, determined by performing a tibial compression test, looking for what is called "tibial thrust".

Secondary tears of the meniscus can result.

Once torn, and despite surgical treatment, osteoarthritis (OA) can develop. The main goals of any knee surgery are to restore normal stability and movement, return to full function, and slow the development or progression of osteoarthritis.

Does My Dog Really Need Surgery?

Some dogs (published data suggests about 15%) will recover reasonably good clinical function without surgery, most being small or toy dogs less than 15-20 lbs. However, many of these dogs will develop significant arthritis and may be chronically painful as a result.

For most dogs of any size, and particularly for large, active dogs, surgery is the best way to return them to full function and lessen problems with OA.

While not a medical emergency, by operating sooner there is less risk for meniscal tearing and OA. Since almost all partial tears progress to complete tears (these ligaments don’t generally heal), delaying surgery doesn’t make sense.

What About Leg Braces or Other Medical Treatment?

There are no scientific reports of leg braces successfully helping manage CCL disease in dogs. Usually, they are not helpful or well-tolerated.

There is no evidence that “alternatives” to surgery advertised for humans, such as joint supplements, acupuncture, etc., will help dogs. Some medical therapy can be helpful before and in conjunction with surgery, and your veterinarian or the surgeon can advise you on this. However, CCL disease in dogs should be considered a surgical disease.

LateralStiflepostTPLO_KarenJames.png - Caption. [Optional]

![LateralStiflepostTPLO_KarenJames.png - Caption. [Optional] lateral (side) radiograph of knee post-surgery showing plate of tibia](/AppUtil/Image/handler.ashx?imgid=8563671&w=&h=)

View of dog's stifle (knee) after TPLO surgery. Image courtesy of Karen James

How Is TPLO Performed?

Radiographs taken by your regular veterinarian may not give enough information for the surgeon, as special measurements will need to be taken. Specially positioned knee and lower leg X-rays are taken before surgery.

The knee joint will be inspected either by making a small incision in the joint capsule (arthrotomy) or by insertion of an arthroscope (a thin rigid tube with a camera and magnification, connected to a TV monitor in the operating room—arthroscopy). The surgeon will inspect the health of the joint cartilage, confirm the status of the cruciate ligaments, and assess the health of the meniscal cartilage. Torn or damaged tissues are removed, and the joint is irrigated with large volumes of sterile fluid to remove any debris or enzymes that trigger inflammation. Once the joint has been treated, the stabilizing procedure begins.

An incision is made along the inner (medial) aspect of the knee and upper part of the shin. A curved, powered saw creates a semi-circular cut through the upper tibia. The now freed tibial plateau is rotated using the pre-op X-rays as the guide and then held in place with a metal (stainless steel or titanium) bone plate through which multiple screws attach the plate to the bone.

A metal pin may be added to secure the bone. Ideally, the plate presses the two parts of bone tightly together (called compression), which results in a more stable repair, faster healing, and fewer complications.

The surgeon will perform a tibial compression test to confirm that the TPLO has accomplished its primary goal of eliminating dynamic instability.

The wound is flushed with a sterile saline solution, and the various tissue layers are closed with sutures. External (skin) stitches or staples may or may not be present.

Post-operative X-rays are taken to assess the quality of the operation and to look for any immediate concerns that could affect the outcome. Limbs may or may not be bandaged after surgery.

Aftercare

Depending on the type of anesthesia and pain medications used, patients may be discharged the same day or spend one to two days in the hospital. Most dogs will not have any bandages on their leg when sent home. Just like with a traumatic broken bone, it takes time for the osteotomy to knit together, and during that time, your dog needs to have very controlled activity to avoid disruption of the repair. healing time varies between eight and twelve weeks on average, depending on patient age, overall health status, and how well the osteotomy was compressed. Surgeon recommendations for post-op physical rehabilitation therapy vary, but usually, some easy-to-do physical rehabilitation therapy will be demonstrated for you to do at home. Your dog may also be seen by a local veterinary physical rehabilitation therapist for more intensive/specialized PT.

X-rays are usually scheduled around eight weeks after surgery to assess how your dog uses their leg and to determine how far along the bone healing has progressed. X-rays may be ordered sooner than eight weeks if you or the surgeon have concerns about possible complications. X-rays beyond eight weeks may be prescribed if healing isn't far enough along at the eight-week mark. Once the bone appears sufficiently healed and the physical exam is satisfactory, the activity restrictions will be gradually lifted, and your dog will return to full activity. Further physical rehabilitation therapy may or may not be recommended.

Potential Complications of TPLO

There is no surgery of any kind that is risk-free, and TPLO has a list of known potential complications. These can be broken down into minor complications and major complications. Minor complications include superficial wound breakdown or infection, inflammation of the tendon between the kneecap and tibia, and other issues that are either self-limited and resolved on their own or are easily resolved with treatment. Major complications include loosening/breakage of the plate or screws, fractures of the lower leg, deep infection, and failure of the osteotomy to heal.

Even these complications can usually be resolved successfully, although they might require further surgery, ongoing medical treatment, and time. Avoidance of complications is best accomplished by choosing a surgeon who is very experienced with the procedure and is attentive to details (you can ask the surgeon what their credentials are, how many TPLOs they do per week, and what their long term success rate is), and by diligently following the discharge instructions, particularly with respect to activity restriction and not allowing your dog to lick their incision.

One complication that can be seen with all cruciate surgeries (not just TPLO) is a post-operative tearing of the meniscal cartilage (referred to as a “late meniscal tear”). Operations such as TPLO that eliminate dynamic instability are better at preventing such late meniscal tears, but a small percentage of knees develop this problem.