Normal urinary tract showing kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. This is called a half shell view as if the tract were opened vertically for viewing. Illustration by Wendy Brooks

Transitional cell carcinoma (frequently abbreviated to TCC) is a particularly unpleasant malignant tumor of the urinary bladder. This tumor type is also sometimes called urothelial carcinoma. In dogs, it usually arises in the lower neck of the bladder, where it is virtually impossible to surgically remove, and causes a partial or complete obstruction to urination. The urethra (which carries urine outside the body) is affected in over half the patients diagnosed with TCC; the prostate gland of male animals may also be involved. In cats, the site of the tumor within the bladder is more variable, which means we are less able to predict whether a mass is likely to be a benign polyp or a malignant tumor based on its location. Bloody urine and straining to urinate are typically the signs noted by the owner, whether the patient is a dog or a cat. These signs are, of course, exactly what would be expected in the event of a bladder infection (which is frequently present concurrently with the tumor), making diagnosis somewhat challenging as both conditions produce similar symptoms.

Why is this Tumor Called a Transitional Cell Carcinoma? Is Something in Transition?

Urinary tract with a transitional cell carcinoma growing in the bladder neck and down the urethra. Illustration by Wendy Brooks

Epithelial cells are cells that line areas of the body that interface with the outside environment. There are many different types of epithelial cells depending on the immediate environment they contact. The skin, for example, is a barrier against irritants and wounds. The tough cells that make up the skin are called squamous epithelial cells because of their flat, overlapping, scale-like design that helps them form a barrier similar to the shingles of a rooftop. The epithelial cells of the respiratory tract secrete lubricant but also are designed to trap inhaled particles in secreted mucus and use tiny hair-like cilia to push them out of the lower tract and back upward, where they can be coughed up. These are called ciliated columnar epithelial cells.

The urinary bladder is lined by transitional epithelial cells. They must protect the body from the caustic urine inside the bladder, but also must maintain this barrier when the bladder stretches and distends with larger volumes of urine. Transitional cell carcinoma is a tumor of the transitional epithelial cell lining of the urinary bladder.

While bladder tumors are somewhat rare as types of cancers go in pets, more than half (and possibly up to 70%) of the bladder tumors developed by pets are transitional cell carcinomas.

What Causes This Tumor?

As with most cancers, we do not know many specific causes. Presumably, repeated exposure to carcinogens in the urine is an important cause. We know that chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide is one cause. We know that female dogs tend to get more transitional cell carcinomas than male dogs, possibly because females do less urine marking and are thus possibly storing urinary toxins longer. In cats, however, males have an increased risk compared to females. Urban living and obesity have been found to increase the risk of the development of this tumor. We know that Shetland sheepdogs, West Highland White terriers, Beagles, and Scottish terriers seem to be predisposed breeds. Beyond this, specifics remain unknown.

A recent study showed that exposure to phenoxy herbicide-treated lawns increased the risk of developing TCC in the Scottish terrier. Another study investigating TCC in Scottish terriers found that the risk for the development of this tumor could be reduced by feeding yellow/orange or green-leafy vegetables at least three times per week.

The average age at diagnosis in dogs is 11 years. The median age at diagnosis in cats is 15 years.

What Kind of Testing is Needed to Identify this Tumor?

Bloody urine with straining can be caused by many other conditions besides cancer. A severe bladder infection, a bladder stone, or feline lower urinary tract disease would be far more common and must be explored first. In other words, reaching a diagnosis is a step-by-step procedure whereby the most common conditions are individually ruled out until a diagnosis is confirmed.

First Step: Urinalysis and Culture

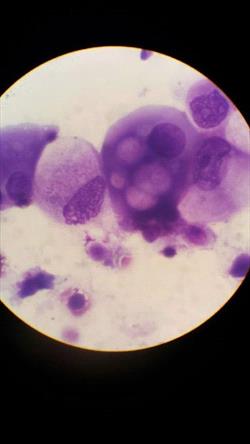

Urine Sediment Cytology Transitional Cell Carcinoma

Urine sediment cytology with cells consistent with transitional cell carcinoma. Photo courtesy of Dr. Delphine Reich.

Many people are confused by the difference between these two tests. A urinalysis is an analysis of urine including a brief chemical analysis and a microscopic examination of the cells contained in the sample. A culture involves plating a sample of urine sediment on a growth medium, incubating for bacterial growth, identifying any bacteria grown, and determining what antibiotics are going to be effective.

Urinalysis and culture will rule in a bladder infection. (A documented infection absolutely does not rule out a tumor, as tumors may easily become infected.)

About 30 percent of TCCs will shed tumor cells into the urine, which may be identified as such during urinalysis.

If a bladder infection is present, it may be worthwhile to treat it with the appropriate antibiotic and see if the clinical signs resolve. If signs do not resolve or if they promptly recur, further testing is definitely in order.

Second Step

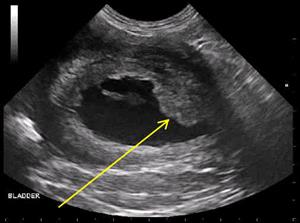

Ultrasound image of a transitional cell carcinoma in a dog's bladder neck. (Photo credit: DVMSound)

If no infection is found, if the urinalysis is normal despite obvious symptoms, if symptoms do not resolve with treatment for infection, or if there is some other reason to be suspicious of a continuing problem, imaging (usually radiographs or ultrasound) would be the next step. A bladder stone would be a vastly more common scenario than a tumor, but it may not be possible to rule out both of these with one test. Radiography is generally less costly and more available than ultrasound, but ultrasound offers the ability to view soft tissue structures inside the bladder, which radiography cannot. This means that tumors are not visible to radiographs (though most stones are) while both stones and tumors are generally visible to ultrasound.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound uses sound waves to create an image of structures within the urinary bladder. This presents a non-invasive way to detect radiolucent stones, polyps, or tumors within the bladder. If a growth is found, it is tempting to sample the cells by needle aspirate; however, the TCC is famous for seeding other organs via needle track so it is best not to attempt aspiration. Sampling is best done by cystoscopy (see below). Ultrasound is helpful in determining the extent of tumor spread after diagnosis has been confirmed (see below). Ultrasound is not available in all hospitals, and sometimes referral is necessary.

Radiography

The main use of radiography at this point is to rule out obvious bladder stones, as they are a common cause of bloody urine and urinary straining. Stones in the bladder provide an explanation for the symptoms and the focus can be shifted to managing stones (removing the stones and preventing new ones from developing). Because radiography cannot distinguish urine from bladder tissue, plain radiographs cannot show tumors without special contrast agents. However, if stones are found, there is usually no reason to look further.

A Newer Test for Dogs: The BRAF Mutation Test

A non-invasive test for TCC has been validated for dogs. It turns out that 85 percent of canine transitional cell carcinomas have a specific mutation in a gene called BRAF. This mutation can be detected in a urine sample, sometimes well before the tumor is visible via the special imaging described. The BRAF test can be used to screen apparently normal dogs of an at-risk breed or it can be used to investigate a dog with symptoms when there is a question of a tumor. The test is not available for cats, and it requires 30 cc of urine (a relatively large sample). Remember that 15 percent of dogs with TCC do not express this BRAF mutation and will test negative. Many dogs with TCC that test negative on the BRAF test can instead be identified with a different genetic test called BRAF-PLUS. This test is also done on a urine sample. Between them, the two tests can detect about 95 percent of dogs with TCC. The BRAF and BRAF-PLUS tests make excellent complementary tests if there is any ambiguity in the imaging. These tests are completely different from the BLAT (bladder tumor antigen test), which was not very helpful as it was not accurate in bloody urine.

Finding a mass in the neck of the bladder, even with inconclusive tissue samples, is often all that is needed to diagnose transitional cell carcinoma.

Third Step

If an explanation for the patient's symptoms has still not been determined at this point, specific imaging methods are needed to see inside the urinary bladder. This imaging can be done with contrast radiography, where a special dye is injected into the bladder to outline any solid material inside it. For a more detailed exploration, cystoscopy threads a tiny camera through the urinary tract to view and possibly even biopsy the bladder wall.

Other Techniques

A tissue sample, of course, is ideal for confirming the diagnosis and cystoscopy generally requires referral. Sometimes a urinary catheter can be placed and manipulated in such a way as to harvest cells through the tumor. A rectal examination sometimes reveals swelling in the area of the urethra that would be highly suspicious of a transitional cell carcinoma in a patient with consistent symptoms.

Fourth Step

So at this point, a growth in the bladder has been identified. If the patient is a dog and the growth is in the bladder neck (and the BRAF mutation test is positive), this may be all the doctor needs to know but if there is any question about the status of the growth (negative BRAF Test, growth in an unusual bladder area, etc.), tissue sampling is needed to confirm the diagnosis. Ultrasound guidance can assist with a needle aspirate of the growth, but this is generally discouraged as the TCC is able to seed normal tissue with tumor as a needle is passed through it. More appropriate ways to get a sample include traumatic catheterization (where a sharp urinary catheter is passed and used to slice off or aspirate a piece of the growth; surgery (where the bladder is opened up and tissue is removed for evaluation); or cystoscopy (where a small camera is passed into the urinary tract and tiny instruments can sample the growth). This last option requires a large enough urinary tract opening to accommodate the equipment; male cats are not large enough.

Transitional Cell Carcinoma Has Been Diagnosed. Now What?

When your pet is diagnosed with cancer, most people want to know how long their pet has to live and what treatments are available. Prognosis depends on the stage of the disease (i.e., whether the tumor is invading other local organs, whether there is evidence of lymph node spread, and whether there is evidence of distant tumor spread).

In one study, the median survival time was 118 days for dogs with evidence of tumor invasion of other local organs compared with 218 days for dogs with no evidence of invasion beyond the urinary bladder.

Dogs with no involvement of local lymph nodes had a 234-day survival time compared to 70 days for dogs with local lymph node involvement.

Dogs with evidence of distant tumor spread had a median survival time of 105 days, while those without distant spread had a survival time of 203 days.

In one study (Wilson et al, Journal of the AVMA; July 2007) involving of 20 cats with TCC, the median survival time was 261 days (this statistic includes cats with various treatments including no treatment).

A belly ultrasound is needed to assess the involvement of local lymph nodes and determine whether or not other organs have been invaded. Radiographs of the chest are the usual way to screen for distant tumor spread; most tumors will spread to the lung, leaving visible round opacities there.

What are the Treatment Options?

Anyway you look at it, transitional cell carcinoma is bad news. It is aggressively malignant and generally grows in an area not very amenable to surgical removal. If the tumor becomes so large and deeply invasive that the patient cannot urinate, an unpleasant death ensues in a matter of days. Ideally, the tumor is discovered and addressed before it gets to this point. There are two approaches that can be explored: definitive treatment (basically treating aggressively with the intent to achieve a long remission or even cure) and palliative treatment (treating so as to restore temporary comfort only).

Surgical Options

Partial Removal of the Bladder (Palliative Treatment)

If the tumor is fairly small at the time it is detected (there is room enough for margins of 3 cm of the normal bladder to be removed around the tumor), it may be worth attempting to remove it and this means removing part of the bladder. If one is very lucky, complete removal or long-term survival is possible. (In one study, over half the patients were alive a year after surgery!) Problems with this therapy include: the fact that it is not possible to determine with the naked eye what the margins of the tumor actually are (so it is easy for the surgeon to believe they have removed enough tissue when in fact there is more), and reduced storage capacity of the remaining bladder after surgery leads to need to urinate more frequently. If recurrence happens, it generally does so within one year of surgery and is thought to occur from either inadequate tumor removal during surgery or the development of a new tumor via the same mechanism that led to the original tumor. There is evidence that using cyclooxygenase-inhibiting anti-inflammatory medications (deracoxib, piroxicam) has activity against the TCC and can assist in the prevention of recurrence; still, 80 percent of tumors will eventually recur.

Complete Removal of the Bladder (Definitive Treatment)

Complete removal of the urinary bladder is just as invasive as it sounds. The benefits of this drastic procedure include long-term control of the tumor, even if the tumor is large (median survival times are greater than 6 months in patients not receiving any other treatment), and control of the pain associated with the tumor.

The main problem with this surgery is the resultant incontinence. The kidneys (where urine is produced) normally deliver urine to the bladder for storage via tiny tubes called ureters. After the bladder is removed, the ureters are attached to the colon so that the patient effectively passes urine rectally along with stool. Alternatively, the ureters can be attached to the vagina or another area.

This is a very radical surgery, and potential complications can include scarring of the ureters and loss of kidney function, infection, and blood biochemical abnormalities. Special diets are required after surgery as well as long-term antibiotics, frequent blood test monitoring, and free access to an area for urination or pet diapers will be needed.

Permanent Urinary Catheter (Palliative Treatment)

A permanently placed urinary catheter can be implanted in the patient’s urinary tract to create more comfortable urination. The placement of a foreign body in this way will predispose the patient to bladder infection, and frequent screening cultures will be needed; still, in one study, six out of seven owners reported satisfaction with the results. Obviously, this procedure does nothing to hinder the tumor’s growth. Owners will need to empty the bladder with a drainage tube at least three times a day to avoid stagnation of urine. The entrance to the catheter must be cleaned daily. Tube dislodgement is a serious complication. Newer tubes are short and a longer drainage tube is attached during bladder emptying. More traditional permanent catheters are longer and will require some sort of wrap or garment for protection. If a tube dislodges, it must be replaced within 48 hours as scar tissue rapidly forms to close the opening into the bladder. Sedation is required for tube replacement; it is not something an owner can do at home.

Urethral Stenting (Palliative Treatment)

In this procedure, a metal stent is placed in the urethra to allow urine passage through the tumor. This procedure is similar to the permanent catheter but is more high-tech. The stent is placed either surgically or with a video radiography called fluoroscopy. The procedure is relatively simple and not invasive, but does require specific equipment. Urinary incontinence is unfortunately a common problem after this procedure (affecting 39 percent of dogs that have it done) and special garments/diapers may be needed indoors. Female patients are more predisposed to incontinence issues following stenting.

Laser Ablation with Chemotherapy (Palliative Treatment)

A study was published in the February 15, 2006, issue of the Journal of the AVMA where seven dogs with transitional cell carcinomas were treated with a combination of laser ablation, piroxicam (see below), and mitoxantrone (see below). Laser ablation has been used for many years in humans with urinary tract cancer. In short, a surgical laser is used to vaporize the tumor from the surface of the bladder and urethra. In the study above, the eight dogs received this treatment followed by chemotherapy, and their symptoms and survival were tracked. The median disease-free interval (i.e., the time without significant symptoms) was 200 days, and the median survival time was 299 days. These survival times were felt to be similar to those achieved with chemotherapy alone and no surgery at all; however, a more lasting resolution of symptoms was felt to have been achieved with this combination treatment. Please note that only seven dogs were studied (an eighth received treatment but died after the first chemotherapy treatment from an automobile accident); information from a larger population would be helpful in solidifying these interpretations. Furthermore, laser ablation seems to be mostly an option for female dogs because of the angles needed to access the tumor with the laser. It can be done in males, but it is more invasive surgically.

Medication (Chemotherapy)

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (Piroxicam, Deracoxib, Firocoxib)

These medications are anti-inflammatory drugs frequently used to treat pain in dogs, but they also appear to have actual anti-carcinoma activity. Piroxicam is the NSAID upon which most research has been conducted. In one study of 62 dogs, three percent experienced complete remission, 14 percent had tumor size reduced by more than 50 percent, and 56 percent of patients experienced no tumor growth during the period of the study. The median survival time was 195 days. The Cox-2 inhibiting NSAIDs are safer, next-generation anti-inflammatories, and several of these, too, seem to also have anti-tumor activity. NSAIDs can be used alone against TCC or they can be used to enhance the effectiveness of more aggressive chemotherapy.

Mitoxantrone

A combination of piroxicam and mitoxantrone has been studied and yielded a measurable response in 35 percent of patients. Approximately 18 percent had intestinal side effects and 10 percent had kidney-related side effects. The median survival time was 350 days. For many oncologists, this protocol is the first choice in therapy. Daily oral piroxicam is used, and intravenous mitoxantrone is given every three weeks for four treatments.

Carboplatin

A combination of carboplatin and piroxicam was able to achieve a higher remission rate (50-70%) but had more potential for side effects and shorter overall survival times.

Gemcitabine

Gemcitabine combined with piroxicam was able to generate a median survival time of 230 days, 5% complete remissions, 21% partial remissions, and 50% stable disease.

Radiation Therapy

In the past, radiation for bladder tumors has been problematic because of how close the large intestine is. In other words, it has been hard to irradiate the bladder tumor without also irradiating the large intestine and causing scarring or other radiation injury. Newer technology has allowed for 3D imaging with CT scans to provide for intensity-modulated radiotherapy. This has allowed for better targeting of the tumor. (A study of 21 dogs revealed a median survival of 654 days.) Specifically equipped facilities are required to deliver radiation therapy, and this special new technology may not be readily available, so if you elect this sort of treatment, some sort of travel is likely to be needed.

Links

A consultation with an oncology specialist is recommended for more details on specific treatments or if your veterinarian is uncomfortable treating TCC. Ask your veterinarian to arrange a referral.

Cancer treatment for pets can be expensive and emotionally exhausting. Sometimes, participation in a study where treatment is free is helpful. Animal Clinical Investigation LLC is a Maryland-based Limited Liability Company founded by Chand Khanna, DVM, Ph.D., Diplomate—American College Veterinary Medicine (Oncology).