Giardia_CDC.gif

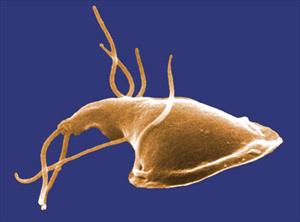

Electron micrograph of a Giardia trophozoite. Photo courtesy CDC

What is Giardia?

Giardia are single-celled organisms, infectious to many types of animals (including humans) all over the world. As you can see in the above image, Giardia organisms have little whip-like tentacles called flagella that classify them as flagellates. They use their flagella to move around from place to place, but when they find a spot where they wish to stay (like a cozy nook in the host's intestine), they use a suction cup-like structure (visible in the image) to attach. Their presence in the host intestine can cause diarrhea, though some hosts are symptom-free carriers. Different types of Giardia infect different types of animals; it is rare for Giardia from a pet to transmit to a human; furthermore, dog and cat Giardia species are separate and are unlikely to cross from dog to cat or vice versa.

Giardia has two forms: the trophozoite and the cyst. The trophozoite is the form that lives within the host, swimming around and attaching with its suction cup. The cyst, however, is the form that lives out in the environment. Trophozoites round up to cysts as they approach the colon and then are passed in feces. Trophozoites that don't round up into cysts and form shells before passing into the cold, cruel world cannot withstand the temperature/moisture variability of the outside world. Cysts are the contagious stage. Trophozoites are in the parasitic stage.

Giardia Transmission

As mentioned, trophozoites and cysts may be passed in fresh feces, but only the hard-shelled little cysts can withstand the conditions of the outside world. The cysts live in the environment (outside the host's body) potentially for months until they are consumed by a host. Inside the host, the cyst's shell is digested away, releasing two trophozoites into the intestine, and the cycle begins again. Contaminated water is the classical source of a Giardia infection.

When a fecal sample is analyzed, the appearance of the Giardia organism depends on whether the sample is freshly obtained or if it has been outside of the host's body for a while. Giardia organisms begin to round up into cysts in a matter of hours. The active trophozoites rather look like funny faces with the two nuclei forming the eyes and median bodies forming the mouth. Cysts look a bit more generic.

In the environment, cysts survive in water and soil as long as it is relatively cool and wet. A host animal will accidentally swallow a cyst when drinking from a puddle, or toilet, or when licking fur. After the cyst has been swallowed, the cyst's shell is digested away, freeing the two trophozoites that go forth and attach to the intestinal lining.

As mentioned, the trophozoite will swim to a spot using its flagella and attach with its suction cup (more correctly called its "ventral disc"). Trophozoites tend to live in different intestinal areas in different host species but will move to other areas depending on the diet the host is eating. The trophozoite may round itself up and form a cyst while still inside the host's body. If the host has diarrhea, both trophozoites and cysts may be shed in diarrhea; either form can be found in fresh stool.

After infection, it takes 5 to 12 days in dogs or 5 to 16 days in cats for Giardia to be found in the host’s stool. Diarrhea can precede the shedding of the Giardia. Infection is more common in kennel situations where animals are housed in groups.

How Does Giardia Cause Diarrhea?

Infection seems to cause problems with normal intestinal absorption of vitamins and other nutrients. Diarrhea is generally not bloody with a Giardia infection. Immune-suppressive medications, such as corticosteroids, can re-activate an old Giardia infection. We do not know why some infected hosts get diarrhea while others never do.

Diagnosis

In the past, diagnosis was difficult. The stool sample being examined needed to be fresh, plus Giardia rarely showed up on the usual fecal testing methods used to detect other parasites. Several tricks have been developed to make Giardia easier to find (special stains, using special processing solutions, etc.), but what has made the biggest difference in the diagnosis of Giardia is the ELISA test kit, which is similar in format to a home pregnancy test. This method has dramatically improved the ability to detect Giardia infections and the test can be completed in just a few minutes while you wait.

Giardia shed organisms intermittently and may be difficult to detect. Sometimes pets must be retested in order to find an infection, and asymptomatic carrier animals are common. It should also be mentioned that the ELISA test can remain positive for some time after the infection has been eradicated so if re-testing is desired after a positive test, another test format may be more helpful than the ELISA test kit.

Giardia upper surface

This photo shows the upper surface of a Giardia protozoan isolated from a rat’s intestine. Photo by Dr. Stan Erlandsen and Dr. Dennis Feely, Courtesy of the CDC.

Treatment

A broad-spectrum dewormer called fenbendazole (Panacur®) seems to be the most reliable treatment at this time. Metronidazole (Flagyl®) has been a classical treatment for Giardia but studies show it to only be effective in 67% of cases. For some resistant cases, both medications are used concurrently. Febantel is also commonly used for Giardia as it is converted to fenbendazole in the body.

Because cysts can stick to the fur of the infected patient and be a source for re-infection, the positive animal should receive a bath at least once in the course of treatment. At the least, the patient should have a bath at the end of treatment, plus it is especially important to promptly remove infected fecal matter to minimize environmental contamination.

Can Humans Be Infected?

The short answer is only rarely, so the concern is pretty low in general. However, maintain good hygiene practices such as regular hand-washing and removing fresh pet fecal matter promptly, as mentioned.

That said, here is a more detailed answer: Giardia duodenalis is classified into several subcategories called assemblages and designated A through G. Some assemblages are specific as to which host animals they can infect, and other assemblages are not so picky. Assemblage F, for example, only infects cats, and assemblages C and D only infect dogs but assemblage A will infect dogs, cats, people, rodents, wild mammals, and cattle. Common testing methods do not indicate what assemblage has been detected, so there is always a possibility of human transmission if the assemblage is unknown.

Environmental Decontamination

Giardia cysts are killed in the environment by freezing temperatures and by direct sunlight. If neither of these is practical for the area to be disinfected, a chemical disinfectant will be needed. Organic matter such as dirt or stool is protective of the cyst, so on a concrete surface, do basic cleaning before disinfecting. Quaternary ammonia compounds can be used to kill Giardia cysts.

Animals should be thoroughly bathed before being reintroduced into a clean area. A properly chlorinated swimming pool should not be able to become contaminated. As for areas with lawns or plants, decontamination will not be possible without killing the plants and allowing the area to dry out in direct sunlight.

A Footnote on Vaccination

A vaccine against Giardia was previously available, not to prevent infection in a vaccinated pet but to reduce the shedding of cysts by the vaccinated patient. In other words, the vaccine was designed to reduce the contamination of a kennel where Giardia was expected to be a problem. This would be helpful during an outbreak in a shelter or rescue situation but is not particularly helpful to the average dog owner who wants to simply prevent infection. Because of the limited usefulness of the vaccine, manufacturing was discontinued in 2009.

In Summary:

- Giardia is a parasite that sticks to its host's small intestine to feed.

- It has two forms: one that lives in the environment (cyst) and one that lives in the host (trophozoite).

- Cysts are the contagious stage, and trophozoites are in the parasitic stage.

- Transmission is by the fecal-oral route from infected stool or contaminated water.

- After infection, it takes 5 to 12 days for dogs or 5 to 16 days for cats for Giardia to be found in the stool.

- Infection is more common in kennels or shelters where animals are housed in groups.

- Giardia causes diarrhea ranging from minor to severe. Veterinarians don't know why some infected hosts get diarrhea while others never do.

- Giardia rarely transmits from a pet to a human or vice versa.

- Diagnosis requires a fresh fecal sample. Several tests may be needed as false negatives can occur.

- Treatment includes dewormers and metronidazole (antibiotic).

- A low-residue, highly digestible diet may be beneficial until stools are firm.

- Because infective cysts can stick to fur, patients should be bathed frequently during and at the end of treatment.

- The environment has to be cleaned after every case because it is so contagious. Giardia can be killed with common disinfectants. Quaternary ammonia compounds are the most effective.

- Giardia cysts are killed in the environment by freezing temperatures and by direct sunlight.

- To kill Giardia on a concrete surface, do basic cleaning before disinfecting.

- Lawns and plants cannot be decontaminated without killing the plants and allowing them to dry out in direct sunlight.

- No vaccine is available.

Additional information from the Companion Animal Parasite Counsel (CAPC): DrontalPlus® is effective in treating Giardia in dogs when administered per label directions.

CAPC Board majority opinion is that asymptomatic dogs may not require treatment.

Back to top