Many injuries and physical disorders represent life-threatening emergencies, but there is only one condition so drastic that it overshadows them all in terms of rapidity of consequences and effort in emergency treatment: the gastric dilatation and volvulus – the bloat.

What is it, and Why Is It So Serious?

stomach developing bloat normal vertical

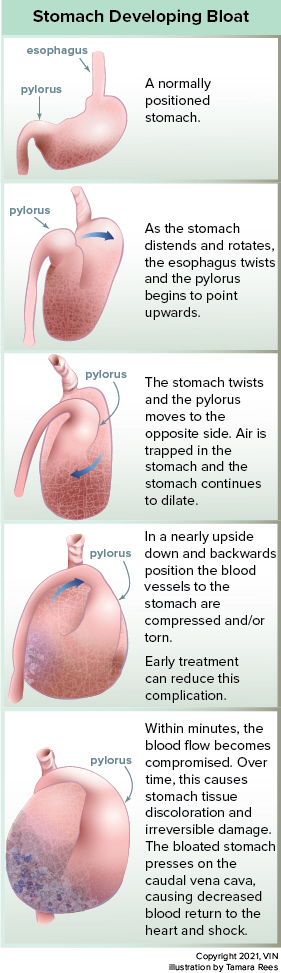

The normal stomach sits high in the abdomen and contains a small amount of gas, some mucus, and any food being digested. It undergoes a normal rhythm of contraction, receiving food from the esophagus above, grinding the food, and moving the ground food out to the small intestine at its other end. Normally, this proceeds uneventfully except for the occasional burp.

In the bloated stomach, gas and/or food stretches the stomach many times its normal size, causing tremendous abdominal pain. For reasons we do not fully understand, this grossly distended stomach tends to rotate, thus twisting off not only its own blood supply but the only exit routes for the gas inside. The spleen, which normally nestles along the greater curvature of the stomach, can twist as well, cutting off its circulation. The distended stomach becomes so large that it compresses the large veins that run along the back, returning the body's blood to the heart, creating a circulatory shock. Not only is this collection of disasters extremely painful, but it is also rapidly life-threatening. A dog with a bloated, twisted stomach (more scientifically called gastric dilatation and volvulus) will die in pain in a matter of hours unless drastic steps are taken.

What Are the Risk Factors for Developing Bloat?

Dogs weighing more than 99 pounds have an approximate 20 percent risk of bloat. The risk of bloating increases with age.

Classically, this condition affects dog breeds that are said to be deep-chested, meaning the length of their chest from backbone to sternum is relatively long while the chest width from right to left is narrow. Examples of deep-chested breeds would be the Great Dane, Greyhound, and the setter breeds. Still, any dog can bloat, even dachshunds and chihuahuas.

stomach developing bloat vertical

Classically, the bloated dog has recently eaten a large meal and exercised heavily shortly thereafter. Still, we usually do not know why a given dog bloats on an individual basis. No specific diet or dietary ingredient has been proven to be associated with bloat. Some factors found to increase and decrease the risk of bloat are listed below:

Summary of Factors Increasing the Risk of Bloat

- Increasing age

- Having closely related family members with a history of bloat

- Eating rapidly

- Feeding from an elevated bowl

- Feeding a dry food with fat or oil listed in the first four ingredients.

Factors that May Decrease the Risk of Bloat

- Adding moistened food reduced the risk of bloat in some studies. More research is needed to fully understand the implications of this. More research is needed to fully understand the implications of this.

- Happy or easy-going temperament

- Feeding a dry food containing a calcium-rich meat meal (such as meat/lamb meal, fish meal, chicken by-product meal, meat meal, or bone meal) listed in the first four ingredients of the ingredient list.

- Eating two or more meals per day

Contrary to popular belief, cereal ingredients such as soy, wheat, or corn in the first four ingredients of the ingredient list do not increase the risk of bloat.

In a study done by the Purdue University Research Group, headed by Dr. Lawrence T. Glickman:

- The Great Dane was the #1 breed at risk for bloat. (The incidence of bloat in this breed is reported to be 42%. Preventive gastropexy should be considered as described below.)

- The St. Bernard was the #2 breed at risk for bloat.

- The Weimaraner was the #3 breed at risk for bloat.

In the 1993 study from Germany (see below), the German shepherd dog and the boxer had the highest risk for bloat.

How to Tell if Your Dog Has Bloated

Classically, the dog is distressed and makes multiple attempts to vomit, and the upper abdomen is hard and distended from the gas within, though in a well-muscled or overweight dog, the distention may not be obvious. There are other potential emergencies (sudden abdominal bleeding from a ruptured tumor, for example) that might have a similar presentation, so radiographs may be needed to determine what has happened. The hallmark presentation of bloat is a sudden onset of abdominal distention, distress, anxiety, and pain (panting, guarding the belly, anguished facial expression), and multiple attempts at vomiting that are frequently unproductive. Not every dog will have a classic appearance, and some dogs will not have obvious abdominal distention because of their body configuration. If you are not sure, it is best to err on the side of caution and rush your dog to the veterinarian immediately.

What Has To Be Done

There are several steps to saving a bloated dog’s life. Part of the problem is that all steps should be done at the same time and as quickly as possible.

First: The Stomach Must be Decompressed

The huge stomach is by now pressing on the major blood vessels, carrying blood back to the heart. This stops normal circulation and sends the dog into shock. Making matters worse, the stomach tissue is dying because it is stretched too tightly to allow blood circulation through it. There can be no recovery until the stomach is untwisted and the gas is released. A stomach tube and stomach pump are generally used for this, but sometime surgery is needed to achieve stomach decompression.

Also First: Rapid IV Fluids Must be Given to Reverse the Shock

Intravenous catheters are placed, and life-giving fluid solutions are rushed in to replace the blood that cannot get past the bloated stomach to return to the heart. The intense pain associated with this disease causes the heart rate to race at such a high rate that heart failure will result. Medication to resolve the pain is needed if the patient’s heart rate is to slow down. Medication for shock, antibiotics, and electrolytes are all vital in stabilizing the patient.

Also First: The Heart Rhythm is Assessed and Stabilized

A special and very dangerous rhythm problem called a premature ventricular contraction, or "PVC," is associated with bloat and it must be ruled out. If this is the case, intravenous medications are needed to stabilize the rhythm. Since this rhythm problem may not be evident until even the next day, continual EKG monitoring may be necessary. If the disturbed heart rhythm is noted at the very beginning of treatment, this is associated with a 38% mortality rate.

Getting the bloated dog's stomach decompressed and reversing the shock is an adventure in itself, but the work is not yet half finished.

Surgery

All bloated dogs, once stable, should have surgery. Without surgery, the damage done inside cannot be assessed or repaired, plus bloat may recur at any point, even within the next few hours, and the above adventure must be repeated. If the stomach has not untwisted with decompression, the surgeon untwists it and determines what tissue is viable and what is not. If there is a section of dying tissue on the stomach wall, this must be discovered and removed, or the dog will die despite the heroics described above. Also, the spleen, which is located adjacent to the stomach, may twist with the stomach, necessitating removal of the spleen or part of the spleen as well. After the nonviable tissue is removed, a surgery called a gastropexy is done to tack the stomach into its normal position to prevent future twisting.

If the tissue damage is so bad that part of the stomach must be removed, the mortality rate jumps to 28 - 38 percent.

If the tissue damage is so bad that the spleen must be removed, the mortality rate is 32 - 38 percent.

After the expense and effort of the stomach decompression, it is tempting to forgo the further expense of surgery. However, consider that the next time your dog bloats, you may not be there to catch it in time and, according the study described below, without surgery, there is a 24 percent mortality rate and a 76 percent chance of re-bloating at some point. The best choice is to finish the treatment that has been started and have the abdomen explored. If the stomach can be surgically tacked into place, the recurrence rate drops to 6 percent.

Surgery will prevent the stomach from twisting in the future, but the stomach is still able to periodically distend with gas. This is uncomfortable but not life-threatening.

Results of a Statistical Study

In 1993, a study involving 134 dogs with gastric dilatation and volvulus was conducted by the School of Veterinary Medicine in Hanover, Germany.

Out of 134 dogs that came into the hospital with this condition:

- 10% died or were euthanized prior to surgery (factors involved included expense of treatment, severity/advancement of disease, etc.)

- 33 dogs were treated with decompression and no surgery. Of these dogs, eight (24%) died or were euthanized within the next 48 hours due to poor response to treatment. (Six of these eight had actually re-bloated.)

- Of the dogs that did not have surgical treatment but did survive to go home, 76% had another episode of gastric dilatation and volvulus eventually.

- 88 dogs were treated with both decompression and surgery. Of these dogs, 10% (nine dogs) died in surgery, 18% (16 dogs) died in the week after surgery, and 71.5% (63 dogs) went home in good condition. Of the dogs that went home in good condition, 6% (four dogs) had a second episode of bloat later in life.

- In this study, 66.4% of the bloated dogs were male, and 33.6% were female. Most dogs were between ages seven and 12 years old. The German Shepherd dog and the Boxer appeared to have a greater risk for bloating than did other breeds.

(Meyer-Lindenberg A., Harder A., Fehr M., Luerssen D., Brunnberg L. Treatment of gastric dilatation-volvulus and a rapid method for prevention of relapse in dogs: 134 cases (1988-1991) Journal of the AVMA, Vol 23, No 9, Nov 1, 1993, 1301-1307.)

Another study published in December of 2006 looked at 166 dogs that received surgery for gastric dilatation and volvulus. The point of the study was to identify factors that led to poor prognosis.

- A 16.2% mortality rate was observed. The mortality rate for dogs over the age 10 years was 21%.

- Of the 166 going to surgery, 4.8% were euthanized during surgery, and the other 11.4% died during hospitalization (two dogs died during surgery). All dogs that survived to go home were still alive at the time of suture removal.

- 34 out of 166 dogs had gastric necrosis (dead stomach tissue that had to be removed). Of these dogs, 26% died or were euthanized.

- Post-operative complications of some sort occurred in 75.9% of patients. Approximately 50% of these dogs developed a cardiac arrhythmia.

- Risk factors significantly associated with death prior to suture removal included clinical signs of bloating for greater than six hours before seeing the vet, partial stomach removal combined with spleen removal, need for blood transfusion, low blood pressure at any time during hospitalization, sepsis (blood infection, and peritonitis (infection of the abdominal membranes).

(Beck, J.J., Staatz, A.J., Pelsue, D.H., Kudnig, S.T., MacPhail, C.M., Seim H.B, and Monnet, E. Risk factors associated with short-term outcome and development of perioperative complications in dogs undergoing surgery because of gastric dilatation-volvulus: 166 cases (1992-2003). Journal of the AVMA, Vol 229, No 12, December 15, 2006, p 1934-1939.)

It is crucially important that the owners of big dogs be aware of this condition and prepared for it. Know where to take your dog during overnight or Sunday hours for emergency care. Avoid exercising your dog after a large meal. Know what to watch for. Enjoy the special friendship a large dog provides, but at the same time, be aware of the large dog's special needs and concerns.

Prevention: Gastropexy Surgery

Gret Dane playing

Preventive gastropexy is an elective surgery usually done at the time of spaying or neuter in a breed considered at risk. The gastropexy, as mentioned, tacks the stomach to the body wall, which drastically reduces the stomach's ability to twist. The stomach may distend with gas in an attempt to bloat, but since twisting is not possible, this becomes a painful and uncomfortable situation but nothing more serious than that. That said, gastropexy is not an absolute guarantee against twisting but we are talking about a recurrence rate of 76% without gastropexy versus 6% recurrence with gastropexy. A study by Ward, Patonek, and Glickman reviewed the benefit of prophylactic surgery for bloat. The lifetime risk of death from bloat was calculated, along with estimated treatment for bloat versus the cost of prophylactic gastropexy. Prophylactic gastropexy was found to make sense for at-risk breeds, especially the Great Dane, which is at the highest risk for bloat.