gecko stick tail crypto Kevin Wright

Adult leopard gecko with stick-tail with Cryptosporidium varanae. Photo courtesy of Dr. Kevin Wright.

Cryptosporidiosis is the name of a stomach and small intestinal infection reptiles can get that is caused by one of a number of parasites in the genus Cryptosporidium. These parasites can infect many different species of reptiles including lizards, snakes, turtles and tortoises. Here we will be talking about Cryptosporidium in snakes and lizards.

The typical signs of the disease vary according to which type of parasite the snake or lizard has, and which organ is infected. The two main areas that these parasites infect are the stomach and the small intestine. When the stomach is infected, you see signs like vomiting, weight loss, and a firm bulge can often be see in the stomach area. When the small intestine is infected you may see diarrhea, weight loss and poor growth.

This parasite seems to cause quite infectious and progressive disease in snakes and lizards, and is difficult to treat.

In leopard geckos and fat-tail geckos, an infection with Cryptosporidium is often called “stick tail," which is a common term used for extreme weight loss in these geckos: you see a very thin tail that is basically just skin over bone. Stick tail is often accompanied by diarrhea, poor appetite, hiding and spending time in the coolest parts of the enclosure. It often affects more than one gecko per cage and may affect multiple cages in a collection. The disease in geckos is caused by Cryptosporidium varanae, which infects the small intestine.

In snakes, the disease is most commonly caused by Cryptosporidium serpentis that infects the stomach. Affected snakes are unable to digest food and usually will vomit (technically, will regurgitate) an undigested food item three to five days after eating. Untreated, affected snakes and lizards usually die from starvation because they are unable to digest food properly.

The organism is passed in the stool. This infective form, called an oocyst, can survive for years. Only steam and a few disinfectants can kill this oocyst. If the oocyst gets swallowed by another reptile, it infects the small intestine where many of the nutrients from food are absorbed. When the Cryptosporidium parasite infects the cells of the stomach or small intestine, these cells swell. This swelling reduces the ability of the stomach and the small intestine to digest food properly, so the animal becomes thin. In snakes, this swelling can often be seen as a lump in the stomach area.

Snakes and lizards living under suboptimal husbandry conditions such as improper temperature gradients, crowding, unsanitary conditions (allowing droppings, uneaten food and other waste to build up in a cage), poor hygiene (transferring waste and contaminated material between cages), skipping or insufficient length of time spent in quarantine, and collections that bring in a lot of new animals are at a greater risk of acquiring cryptosporidiosis.

People do not get infected by reptile species of Cryptosporidium.

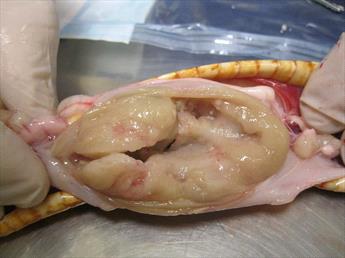

Gastrointestinal mass - corn snake

Corn snake with swollen stomach from Cryptosporidium serpentis seen on necropsy. Photo by Dr. John Lutz.

Affected Lizards and Snakes

Many species of lizards and snakes can be infected by Cryptosporidium. The most commonly diagnosed lizard species in captivity are the leopard gecko (Eublepharis macularius) and the fat-tailed gecko (Hemitheconyx caudicinctus), monitor lizards (Varanus spp.) and crested geckos (Rhacodactylus spp.). Cryptosporidiosis also infects other lizards, such as chameleons and Gila monsters.

Snakes species that are commonly infected include colubrids like the corn snake, other rat snakes and king snakes. Many boa and python species have been infected as well as many different species of venomous snakes.

Given the wide range of reptiles that have been diagnosed with cryptosporidiosis it is likely that almost any snake or lizard species can be infected. Age or sex predispositions are not known for any reptile cryptosporidiosis.

Diagnosis

Your veterinarian will start by taking a thorough medical history and give a physical examination. The snake should also have blood taken for a complete blood count and plasma chemistry in addition to radiographs (X-rays) and a fecal examination.

Cryptosporidium that infects the small intestine can be diagnosed from a fecal sample or a swab from the gecko’s cloaca (vent), which is sent to a diagnostic laboratory to test for Cryptosporidium DNA using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test. For those species that infect the stomach, a stomach wash (fluid in placed into the stomach with a tube and then removed for testing) or a stomach biopsy will be collected for PCR testing.

Treatment

Once you have a diagnosis of cryptosporidiosis, you veterinarian will discuss treatment options with you. Cryptosporidium is difficult to treat and highly infectious to other reptiles.

Your veterinarian may prescribe paromomycin at much higher doses than are normally given to reptiles; it is a drug that can reduce the number of crypto organisms in your lizard. It does not “cure” crypto but helps keep it in low enough numbers for your gecko to recover. Your gecko may need to be on paromomycin for six to eight weeks or more to see improvement, and may need to be on it for one or two days a week as a life-long treatment. If your crypto-positive gecko has other infections, such as flagellated protozoa parasites or bacterial infections of its intestines, your veterinarian can offer appropriate medications. Paromomycin has not been well evaluated as a treatment for snakes and is fairly new even in lizards, and many cases of cryptosporidiosis may not be helped by this drug.

An affected gecko’s intestine may be damaged and not absorbing water and other nutrients properly. Daily soaking in chin-deep, cage-temperature water may be needed to help keep a gecko well-hydrated, or it may need to receive injectable fluids. Liquid diets may be given orally to help a gecko regain weight. In addition, your veterinarian will discuss any husbandry changes that may need to made for your gecko. Give all medications and treatments as directed by your veterinarian and follow recommendations for recheck examinations.

Prevention

The goal is to keep cryptosporidiosis out of the collection, as it is highly transmissible, difficult to treat and even more difficult to disinfect against.

Quarantine

All incoming snakes and lizard should be quarantined to prevent introduction of Cryptosporidium. Your veterinarian will discuss what screening tests to perform and when to perform them; it is important to follow these recommendations. As a general rule, a new reptile should be eating well, maintaining or gaining weight, free from common detectable infectious diseases and appear healthy for one month in lizards, and three months for snakes, before it is released from quarantine or isolation.

Isolate

Affected reptiles should be isolated. This helps prevent further spread of the disease and may remove them from stressful competition with cagemates. If an infection is confirmed, any reptiles that were cagemates or any reptiles that may have otherwise been exposed to the disease should be isolated.

Proper Hygiene and Sanitation

Handle infected reptiles and cages only after you have completed all tasks required for any other reptiles you may keep.

Prognosis

Unfortunately, cryptosporidiosis is not a straightforward disease to treat and many cases will not be cured. If a reptile does not gain weight, increase activity, and show a willingness to eat on its own within three weeks of treatment, its outlook is poor and euthanasia should be considered. The more information your veterinarian has, the better the advice that can be given to you as to your reptile’s chances.