240_F_431977949_cazk2SIEt3BD3PqL7awv3m5BG08PQnZs.j

Photo by Karen James/VIN

Getting a dehydrated body rehydrated is one of the most important capabilities in medicine, whether veterinary or human. A body can survive much longer without food than it can without water, so dogs, cats, and people are at higher risk of dehydration than starvation.

Fluids are given medically in all types of supportive care, trauma, significant diarrhea or vomiting, poisonings, and so on. Dehydrated pets may not be interested in drinking enough water to be able to offset the dehydration, or they may be unable to due to vomiting, and they need to eat and drink to heal. In particular, the liver and kidneys require appropriate hydration to function, otherwise, they cannot perform their critical function of filtering out toxins and waste. Being too dry means that a body cannot metabolize medication properly nor fight disease, and can impair circulation to the point that oxygen is not delivered to the body.

Signs of dehydration include lethargy, lack of appetite, sticky gums, sunken eyes, constipation, low body temperature, and overall not feeling good. Vomiting and diarrhea can contribute greatly to dehydration. Blood tests and physical exam results can tell how dehydrated your pet is.

Intravenous Fluids

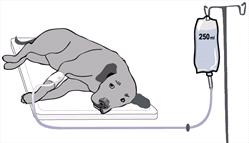

Two methods are used most often to rehydrate pets: an intravenous (IV) line going into one of three main veins, or fluids given under the skin, called subcutaneous injections (often abbreviated as SQ).

Replacement fluids, most commonly lactated Ringer's solution or Hartmann’s solution, and liquid medications can be given in the IV line. A monitored pump is usually used to make sure that the same volume is given consistently.

An IV catheter and line are placed by a veterinarian or credentialed technician. Most often these lines are used when your pet is ill or is about to undergo anesthesia. The most common placement is in the vein that runs along the top of the dog or cat's foreleg. An IV line allows the fluid – whether it is medication or not – to run throughout the whole body quite quickly. It also provides the veterinarian with more control than injections into the skin or muscle, or pills.

A constant rate infusion (CRI) is commonly used for certain medications. The CRI gives your pet a continuous flow maintained at a pre-set rate. The flow doesn't change in volume unless the medical staff changes it. It is helpful for giving pain management medications or drugs with a short half-life because the drug level is maintained at a pre-set rate. It is also helpful for managing blood pressure, supplementing electrolytes, giving sedation or anesthesia, and insulin. With CRI, a drug can be diluted or mixed with other fluids.

Sometimes both fluids and medication can be given at the same time, from different bags going into the same IV line. When your pet is hospitalized, an IV line will stay in as long as your pet is there. Placing it is usually one of the first things done at the hospital, and removing it is the last.

Dog with IV large-leg.jpg

Copyright 2022, VIN / Illustration by Tamara Rees

Subcutaneous (SQ) Fluids

Fluids can be given under the skin – subcutaneous – using a syringe or fluid bag and drip set. Your veterinarian can do this, but so can you. You may need to be taught how to give SQ fluids at home, particularly in cases when your pet is ill but not sick enough to stay in the hospital, has kidney disease, or is geriatric and could use a little help getting some fluids down. Don't panic! It's much easier than you would think to do this at home, and your veterinarian will show you how. Your pet will be less stressed if they don't have to go to the clinic every day or every week. It may also be less expensive since the veterinarian does not have to pay staff time to give the fluids. Each clinic will provide their own instructions when they show you how to do this. The fluids are usually from a bag of fluids, such as lactated Ringer's. You will be given a drip set, which is the tube that connects the bag to the needle, and a fluid bag. Store the fluid bag at room temperature and away from lights because some medications will weaken in bright light.

VIn canto images.jpg

Photo by Karen James/VIN

Your cat may prefer to sit in a box while you give them fluids. Be sure you and your pet will be comfortable for about 10 minutes or so while you give the fluids.

Don't use the needles more than once as they are sharp and sterile when opened for the first time. Using a needle more than once can cause an infection and a bit more pain, and needles are inexpensive, so use a new one every time. Remove the cap from the bottom of the fluid bag but don't let it touch anything, otherwise, it could become contaminated. Pull the covering off of the exit port so you can access the hole into which you put the pointed end of the fluid set. After you've inserted the fluid set, make sure there are no bubbles in the fluid inside the tubing. Once the fluid set is full, close the cover and replace the cap at the end.

Open the wrapping around the needle to expose the round, open end (not the sharp end). Be careful not to let it touch anything other than the fluid drip tubing so it does not become contaminated. Take the cap off from the lower end of the fluid set, place the open end of the needle securely on the end of the drip tubing.

When you are ready, carefully remove the cap from the sharp end of the needle. Pick up a roll of loose skin in a location your veterinarian showed you and push the needle slightly forward while pulling on the roll of skin. The needle should go just under the skin, which is what subcutaneous means. Let go of the skin roll and start the fluids by rolling the dial up on the fluid set lock. Talk to your pet while the needle is under their skin. Some may fall asleep; some may be worried. If your pet is able to eat treats, you may be able to distract them with a treat during the process.

When you have given the prescribed amount, stop the flow by rolling the dial down on the fluid set lock. Then pull the needle out. Put a new needle or the fluid set cap back on as soon as you are through giving fluids to prevent bacteria from getting into the fluid bag. Make sure you dispose of the needle in an approved sharps container and not in the general trash.

It may sound complicated, but it takes longer to describe than it does to do this, and your pet will feel much better when hydrated.