(Formerly known as autoimmune hemolytic anemia or AIHA)

Immune-mediated hemolytic anemia (IMHA) is a condition in which the body’s immune system attacks and removes its own red blood cells, leading to severe anemia, an unhealthy yellowing of the tissues called jaundice or icterus, and an assortment of life-threatening complications. Mortality approaches 70%, so an aggressive approach is necessary. Treatment includes immune-suppressive drugs and possible blood transfusions.

RbcsYantibodies.gif

Red blood cells are coated with Y-shaped antibodies that mark them for removal or destruction. Illustration by Dr. Wendy Brooks

How Red Blood Cells are Normally Removed from the Body

Red blood cells have a natural life span from the time they are released from the bone marrow to the end of their oxygen-carrying days when they become too stiff to move through the body’s narrow capillaries. A red blood cell must be supple and flexible to participate in oxygen delivery and carbon dioxide removal, so when the cell is no longer functional the body destroys it and recycles its components.

When old red blood cells circulate through the spleen, liver, and bone marrow, they are plucked from circulation and destroyed in a process called extravascular hemolysis. Their iron is sent to the liver for recycling in the form of a yellow pigment called bilirubin. The proteins inside the cell are broken down into amino acids and used for any number of things (burning as fuel, building new proteins, etc.)

The spleen uses immunological cues on the surface of red blood cells to determine which cells should be plucked out of circulation. In this way, red cells parasitized by infectious organisms are also removed from circulation along with the geriatric red cells.

Alternatively, some old stiff red blood cells simply burst when they cannot go through narrow passages. In that case (intravascular hemolysis), the components are scavenged and recycled similarly.

When the immune system marks too many cells for removal, serious problems begin.

- Too many red blood cells are removed and the patient becomes weak from lack of blood.

- The liver is overwhelmed by the large amounts of bilirubin it must process. The patient becomes jaundiced, or icteric, which means his tissues become yellow or orange. The extra bilirubin in the urine turns the urine orange or even brown.

- Hemoglobin (oxygen-carrying protein from inside the red blood cell) floats around in the bloodstream in large amounts which can damage the kidneys.

- All those red blood cells coated with antibodies begin to stick to each other and form small clots (embolisms). This begins to block blood vessels, compromising circulation to the organs and creating inflammation as the body tries to dissolve the clots.

This is a life-threatening cascade of events and a 20-80% mortality rate (depending on the study) has been reported with this disease.

PaleMMsCanine_Davidow.png

Dogs and cats may have darkly pigmented gums, as shown here. Note the pale lip (mucous membrane color) that can happen with this type of anemia as shown above. The gums and lips may also take on a yellow tint. If you notice this at home, contact a veterinarian right away.

What Happens During IMHA?

The spleen enlarges as it finds itself processing far more damaged red blood cells than it normally does. The liver is overwhelmed by large amounts of bilirubin and the patient becomes jaundiced (icteric), which means his tissues become a yellow/orange color.

Making matters worse, a protein system called the complement system is activated by these anti-red cell antibodies. Complement proteins can simply rupture red blood cells if they are adequately coated with antibodies, a process called intravascular hemolysis. Ultimately, there aren’t enough red blood cells left circulating to bring adequate oxygen to the tissues and remove waste gases. A life-threatening crisis has emerged; in fact, 20-80% mortality (depending on the study) has been reported with this disease.

Clinical Findings and Test Results

There are several features to IMHA that your veterinarian will be looking for, though not every patient will show them all. To diagnose IMHA, there must be at least one sign of red cell destruction (orange urine, yellow tissues, high bilirubin blood test, for example) plus at least two indicators that the red cell destruction is immune-mediated and not from some other cause (such as zinc toxicity). Indicators of immune-mediated red cell destruction include a positive auto-agglutination test, a positive Coombs test, or the presence of cells called "spherocytes" (see below).

Signs To Watch For

Your pet will be obviously weak. They have no energy and have lost interest in food. Urine is dark orange or maybe even brown. The gums are pale or even yellow-tinged as are the whites of the eyes. There may be a fever. You (hopefully) brought your pet to the veterinarian’s office as soon as it was clear that there was something wrong.

To Review:

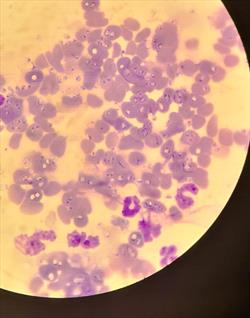

Spherocytes

Spherocytes are special red blood cells produced when red blood cells are not completely removed by the spleen. The spleen cell bites off only a portion of the red cell, leaving the rest to escape back to the circulation.

A normal red blood cell is concave on both sides and shaped like a disc. It is slightly paler in the middle than on its rim. After a portion has been bitten off, it re-shapes into a more spherical shape with a denser red color. The presence of spherocytes indicates that red blood cells are being destroyed.

Autoagglutination

In severe cases of immune-mediated hemolytic anemia, the immune destruction of red cells is so blatant that the red cells clump together (because their antibody coatings stick together) when a drop of blood is placed on a microscope slide. Imagine a drop of blood forming not a red spot but a yellow spot with small red clumps inside it. This finding is especially foreboding.

- The spontaneous clumping of red blood cells is called autoagglutination.

- The formation of an actual clot from all the clumping is called embolization (especially if the clot travels in the circulation).

- When the embolism lodges in a small vessel like a plug and occludes circulation, this event is called thrombosis.

- The condition where embolism is happening and vessels are being plugged is called thromboembolic disease and it is the main cause of death in IMHA patients.

Leukemoid Reaction

Classically, in IMHA the stimulation of the bone marrow is so strong that even the white blood cell lines (which have little to do with this disease but which also are born and incubate in the bone marrow alongside the red blood cells) are stimulated. This leads to white blood cell counts that are spectacularly high.

Additional Helpful Tests

Coomb’s Test Called a Direct Antibody Test)

If a patient is anemic, icteric, or has spherocytes (or worse, autoagglutination) on a blood smear, it is pretty obvious that there is immune-mediated hemolytic anemia. Sometimes, though, it is not so obvious and additional testing is needed. This is exactly where a Coomb's test could be used.

This is a test designed to identify antibodies coating red blood cell surfaces. If there is ambiguity in the patient's presentation, the Coomb's test might be selected to confirm that the anemia is really immune-mediated and not the result of a bleed or non-immune mediated origin such as zinc toxicity, or onion/garlic toxicity.

The Coomb's test has been around for a long time and is not perfect. It can give a false positive in the presence of inflammation or infections (which might lead to harmless attachment of antibodies to red cell surfaces) or in the event of prior blood transfusion (ultimately transfused red cells are removed from the immune system). Despite its limitations, the Coomb's test helps confirm the IMHA diagnosis if other findings are confusing.

Serum Lactate Levels

Lactate or Lactic acid is the natural by-product of anaerobic metabolism. In other words, when the body's organs are deprived of oxygen (perhaps because there aren't enough functioning red blood cells circulating or there are agglutinated red blood cells clogging the capillaries), the organs will switch to anaerobic metabolism. Lots of lactate circulating means lots of tissue does not have enough oxygen, and it is a bad sign. It is such a bad sign that it can be used to predict disease survivors within the first several hours of hospitalization.

In a study of 173 dogs with IMHA (Holahan et al), non-survivors had significantly higher lactate levels at presentation compared to survivors. Dogs that were able to normalize serum lactate levels within 6 hours of hospitalization all survived. Many hospitals monitor lactate levels in IMHA patients as part of the regular assessment of the ability to oxygenate tissue.

Testing for Blood Parasites

Babesia organisms are seen within erythrocytes and also as extracellular organisms. Courtesy Dr. Rebecca Quam.

In most canine episodes of IMHA, an underlying cause cannot be found but it is still worth looking. There are many blood parasites, especially tick-borne infections, that can initiate IMHA. The parasite attaches to the red blood cell and its structures are detected by the immune system. The immune system attacks the parasite but, unfortunately, also attacks the red blood cells as well. Parasites such as Ehrlichia, Babesia, and Anaplasma should be ruled out. If a blood parasite is confirmed, a more targeted therapy can be affected.

Treatment and Monitoring During the Crisis

The patient with IMHA is often unstable. If the hematocrit has dropped to a dangerously low level, then a blood transfusion is needed and quickly. It is not unusual for a severely affected patient to require many transfusions. General supportive care is needed to maintain the patient’s fluid balance and nutritional needs. Most importantly, the hemolysis must be stopped by suppressing the immune system’s rampant red blood cell destruction, and thromboembolism must be prevented. We will review these aspects of therapy.

Transfusion

Compatible blood can last a good 3 to 4 weeks in the recipient’s body. Well-matched whole blood or packed red cells (a unit of whole blood with most of the plasma removed, leaving only a concentrated solution of red blood cells) may last longer. The problem, of course, with IMHA is that even the patient’s own red blood cells are being destroyed so what chance do donated cells have? Cross-matching of red cells is ideal but still may not lead to a good match given the hyperactivity of the patient’s immune response. For this reason, it is not unusual for several transfusions to become necessary during treatment.

Immune Suppression

Corticosteroid hormones in high doses are the cornerstone of immune suppression. Prednisone and dexamethasone are the most popular medications selected. Remember, that the problem in IMHA is that red blood cells are being coated with antibodies that mark them for removal. Antibodies come from lymphocytes and corticosteroid hormones kill lymphocytes, thus taking out the cells that are making the offending antibodies. Even better, corticosteroid hormones also suppress the cells that are removing the antibody-coated red blood cells as well. This allows the patient's red blood cells to survive and continue their job carrying oxygen and carbon dioxide.

Corticosteroids may well be the only immune-suppressive medications the patient needs. The problem is that if they are withdrawn too soon, the hemolysis will begin all over again. The patient is likely to be on high doses of corticosteroids for weeks or months before the dose is tapered down and there will be regular monitoring blood tests. Expect your pet to require steroid therapy for some 4 months; many patients must always be on a low dose to prevent a recurrence.

Corticosteroids in high doses produce excessive thirst, re-distribution of body fat, thin skin, panting, predisposition for urinary tract infection, and other signs that constitute Cushing’s Syndrome. This is an unfortunate consequence of long-term steroid use but in the case of IMHA, there is no way around it. It is important to remember that the undesirable steroid effects will diminish as the dosage diminishes.

Additional Immune Suppression

If minimal response at all is seen with corticosteroids, supplementation with stronger immune suppressive agents is necessary. The most common medication used in this case is azathioprine. This is a serious drug reserved for serious diseases. Please follow the link above to read more about specific side effects, concerns, etc.

Cyclosporine is an immune-modulator, made popular by organ transplantation technology. It has the advantage over other medications of not being suppressive to the bone marrow cells. It has been a promising adjunctive medication in IMHA but may be prohibitively expensive for larger dogs.

Mycophenolate mofetil is another emerging immune suppressive medication that might be prescribed. The goals of these additional medications are similar: to provide extra immune suppression and to reduce the necessary dose of steroids, thus mitigating the steroid side effects.

Do not be surprised if your veterinarian adds a second medication to the prednisolone or dexamethasone and expect months of therapy to be needed.

IMHA has a relapse rate of 11-15%.

Leflunomide is an immunomodulator for patients with immune-mediated diseases when corticosteroids either do not work or cannot be used.

Preventing Thromboembolic Disease

While it is generally agreed that the IMHA patient needs to be anti-coagulated, a definitive drug protocol for doing so has not emerged. Heparin is a natural protein that can be given by injection or by continuous drip. The trick is to keep the already anemic patient from bleeding once coagulation mechanisms have been disrupted. A more pure form of heparin called low molecular weight heparin appears to be an improvement but this form of heparin is substantially more expensive and may be impractical.

Another approach to anticoagulation is to block platelet function by using low doses of aspirin. The problem with aspirin is getting a dose that will inactivate platelets without also increasing the risk of ulceration of the GI tract since aspirin and corticosteroids are generally not compatible. A newer drug called clopidogrel has emerged as an alternative but none of these medications (the heparins not the platelet blockers) have been shown to definitively improve survival rate.

A study by Drs. Anthony Carr, David Panciera, and Linda Kidd at the University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine looked for trends by reviewing 72 dogs with IMHA. Their findings were:

- The only predisposed breed they found was the cocker spaniel.

- Most patients were female.

- The mean age was 6.8 years.

- Timing of vaccination was not associated with the development of IMHA.

- 94% of cases had spherocytes on their blood smears.

- 42% showed autoagglutination.

- 70% also had low platelet counts.

- 77% were Direct Coombs' positive.

- 58% were suspected of having disseminated intravascular coagulation.

- 55% required at least one blood transfusion.

- Mortality rate was 58%.

- Of those that died, 80% had thromboembolism present on necropsy (autopsy).

Prognostic Factors for Mortality and Thromboembolism in Canine Immune-Mediated Hemolytic Anemia. A.P. Carr, D. Panciera, L. Kidd. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2002; 16: 504-509.

Evans Syndrome

A special disaster in IMHA is Evans syndrome where not only are red blood cells being destroyed but platelets are also destroyed (Immune Mediated Thrombocytopenia). If a patient not only has IMHA but also has extremely low platelet numbers, this suggests that Evans syndrome is afoot and the patient should not have treatment to prevent embolism as the platelet loss has already created an inability to clot normally. Evans syndrome has a particularly high mortality rate.

Thromboembolic Disease

This particular complication is the leading cause of death for dogs with IMHA (between 30-80% of dogs that die of IMHA do so due to thromboembolic disease). A thrombus is a large blood clot that obstructs (occludes) a blood vessel. The vessel is said to be thrombosed. Embolism refers to smaller blood clots spitting off the surface of a larger thrombus. These mini-clots travel and obstruct smaller vessels, thus interfering with circulation. The inflammatory reaction that normally ensues to dissolve errant blood clots can be disastrous if the embolic events occur throughout the body.

Heparin, a natural anticoagulant, may be used as a preventive in hospitalized patients or in patients with predisposing factors for embolism.

Why Did This Happen?

When something as threatening as a major disease emerges, it is natural to ask why it occurred. Unfortunately, if the patient is a dog, there is a good chance that there will be no answer to this question. Depending on which study you read, 60-75% of IMHA cases do not have apparent causes.

In some cases, though, there is an underlying problem: something that triggered the reaction. A drug can induce a reaction that stimulates the immune system and ultimately mimics some sort of red blood cell membrane protein. Not only will the immune system seek the drug but it will also seek proteins that closely resemble the drug and innocent red blood cells will be consequently destroyed.

Drugs are not the only such stimuli; cancers can stimulate exactly the same reaction (especially hemangiosarcoma).

Red blood cell parasites create a similar situation, as mentioned, except the immune system is aiming to destroy infected red blood cells. The problem is that it gets overstimulated and begins attacking the normal cells as well.

The possible relationship between recent vaccination and IMHA development is one of the factors that has led most veterinary universities to go to an every 3-year schedule for the standard DHPP vaccine for dogs rather than the traditional annual schedule. The role of vaccination as a trigger for this condition remains controversial as some studies show an association with recent vaccination and others show none. Vaccination involves immune stimulation, however, which may be something to avoid. Check with your veterinarian about how to proceed with future vaccinations.

Dog breeds predisposed to the development of IMHA include Cocker Spaniels, Poodles, Old English Sheepdogs, and Irish Setters.

In cats, IMHA generally has one of two origins: feline leukemia virus infection or infection with a red blood cell parasite called Mycoplasma hemofelis (previously known as Hemobartonella felis). The underlying cause should be sought and addressed specifically in addition to immune suppressive therapy.

Complications

Human gamma globulin transfusion is a treatment that is reserved for patients that don't respond to traditional treatments. The gamma globulin portion of blood proteins includes circulating antibodies. These antibodies bind the reticuloendothelial cell receptors that would normally bind antibody-coated red blood cells. This prevents the antibody-coated red blood cells from being removed from circulation. Human gamma globulin therapy seems to improve short-term survival in a crisis, but, unfortunately, its availability is limited, and it is very expensive.

Another Study

A study by Drs. Tristan Weinkle, Sharon Center, John Randolph, Stephen Barr, and Hollis Erb at Cornell University reviewed 151 dogs with IMHA looking for trends. They found:

- Cocker spaniels and miniature schnauzers were both overrepresented (i.e., felt to be predisposed). These breeds, however, showed the same mortality rate as other breeds.

- Unspayed female dogs were overrepresented.

- Neutered male dogs were more commonly affected than unneutered male dogs (begging the question of whether male hormones might have some protective effect).

- The chance of survival, either long-term or short-term was significantly enhanced by the addition of aspirin to the treatment protocol, especially when combined with azathioprine.

- Adequate vaccination information was not obtained for enough patients to comment on the association with vaccination.

- 89% of affected dogs showed spherocytes on their blood smears.

- 78% showed autoagglutination.

- 70% of patients required at least one blood transfusion.

- Of the 151 dogs studied, 76% survived, 9% died, and 15% were euthanized. Survivors were hospitalized for an average of 6 days. Non-survivors were hospitalized for an average of 4 days.

- 100% of dogs that died or were euthanized showed thromboembolism on necropsy (autopsy).

- Of the dogs that survived 60 days or more, 15% experienced a relapse. Most dogs treated with corticosteroids, azathioprine, and ultra-low dose aspirin did not experience relapse.

[Evaluation of prognostic factors, survival rates, and treatment protocols for immune-mediated hemolytic anemia in dogs: 151 cases (1993-2002). T.K. Weinkle, S.A. Center, J.F. Randolph, K.L. Warner. S.C. Barr, H.N. Erb. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. Vol 226, No 11, June 1, 2005. 1869-80.]

In Summary:

- Background: A healthy body removes old red blood cells from circulation. Iron from old cells is sent to the liver and recycled into a yellow pigment called bilirubin. The immune system is designed to fight off infection. An auto-immune response means the body fights against itself instead of disease and illness.

- Immune-mediated hemolytic anemia (IMHA) is a serious disease with a high death rate. Treatment must be aggressive and not discontinued early for the chance of survival. Transfer to a critical care or emergency facility may be necessary.

- In IMHA, the body's immune system attacks its own red blood cells, leading to severe anemia (low numbers of red blood cells) and other life-threatening complications. With anemia, there are not enough healthy red blood cells left to deliver oxygen to tissues causing weakness.

- Large amounts of oxygen-carrying proteins from the old blood cells can also damage the kidneys as they are destroyed by the body in large numbers.

- The liver cannot process such a large volume of bilirubin (from the old red blood cells), resulting in tissues appearing yellow. Urine can turn orange or brown, and the whites of the eyes may turn yellow. This condition is called jaundice.

- An underlying cause cannot be found in most canine cases, but it is still worth looking into.

- Your pet may not feel like eating, lack energy, have a fever, jaundice, pale gums, and a change in the color of urine.

- Old red blood cells become coated with antibodies that make them sticky so that they form clots. The clots block blood vessels, compromising blood circulation to the organs and creating inflammation.

- A clot that forms from clumped dead red blood cells covered with sticky antibodies is called embolization. The main cause of death in IMHA occurs when blood vessels get plugged with these clots.

- Blood tests will show evidence of IMHA and other related conditions. Your veterinarian will use those results to select the best treatment.

- Treatment includes immunosuppressive drugs and possible blood transfusions.

- Immune-suppressive drugs (to decrease the body attacking itself), like corticosteroids, are the usual treatment for IMHA. The most common medication used is azathioprine, a serious drug reserved for serious diseases.

- Prognosis (outlook) depends on the severity of your pet's case; IMHA has a 20-80% mortality rate. Back to top

IMHA is a serious disease with a high mortality rate. Treatment must be aggressive and not prematurely discontinued if the patient is to survive. Transfer to a critical care or emergency facility may be necessary. Research is ongoing with regard to new therapies.