Discovering Your Cat Has a Bladder Stone

Presumably, you are reading this page because your cat has or had a calcium oxalate bladder stone or your cat has or had a bladder stone that is likely to be a calcium oxalate bladder stone. The stone was most likely discovered in one of these scenarios:

- There was urinary discomfort or bloody urine leading to imaging of the bladder.

- There was an unresolved bladder infection that led to imaging of the bladder.

- The stone was found incidentally while looking for something else.

If your cat has bladder stones, the stones need to be eliminated and their recurrence prevented. Central to this mission is determining the type of stone, and while we may be able to get some information from the urinalysis, we really need to retrieve a stone for analysis to get the story. If we are lucky, the cat will pass a small stone that can be sent to the lab, but most likely we are going to need surgery or one of the other stone retrieval methods reviewed below. Unlike struvite stones, calcium oxalate stones will not dissolve with dietary manipulation, although an attempt can certainly be made at dietary dissolution. If this is unsuccessful, though, we are back to square one and the need to retrieve a stone.

Why Do Cats Develop Calcium Oxalate Bladder Stones?

About 25 years or so ago, cats virtually never developed calcium oxalate bladder stones. Cat bladder stones could reliably be assumed to be made of struvite (a matrix of ammonium-magnesium-phosphate). In those days, feline lower urinary tract symptoms were generally thought to be caused by struvite crystals in the urine, and feline lower urinary tract symptoms were extremely common. The pet food industry responded by acidifying cat foods to prevent crystals from developing. In a way, it worked. Feline lower urinary tract symptoms declined. Male cats with struvite urinary blockages became far less common. The trade-off was that calcium oxalate bladder stones began to develop. Acidifying the body leads to an acid urine pH and more calcium loss into the urine, both factors in the development of a calcium oxalate stone.

Currently, most bladder stones formed by cats are calcium oxalate stones.

Calcium Oxalate Points

- Burmese and Himalayan cats appear genetically predisposed to the development of calcium oxalate bladder stones.

- Most calcium oxalate stones develop in cats between ages 5 and 14 years.

- 35% of cats with calcium oxalate bladder stones have elevated blood calcium (hypercalcemia).

- Cats with calcium oxalate stones tend not to have bladder infections and to have acid urine pH on their urinalysis.

- Obesity is a factor in calcium oxalate stone development.

How to Get Rid of the Stones

Cystotomy (Surgical Removal)

The fastest way to resolve a bladder stone issue is to remove the stones surgically. To accomplish this, the cat is anesthetized, and an incision is made through the belly. The bladder is lifted into view, opened, and stones are removed. Cultures to rule out infection are obtained if not done previously. The bladder is closed in several layers. The belly is closed, and the patient is awakened. Pain medication and antibiotics are routinely used after surgery. The patient usually remains hospitalized for a day or two to observe urination. The stones are sent to the lab for analysis.

It is normal for some blood to be evident in the urine for several days after surgery. Obviously, this is an invasive approach but it does provide rapid resolution, is the traditional approach, and can be performed in most veterinary hospitals.

Cystoscopy and Laser Lithotripsy

A less invasive method involves using a cystoscope, a long skinny instrument that removes stones from the bladder using a small basket-like retrieval accessory. This can only be done with small stones and can only be done in female cats.

For larger stones, laser lithotripsy can be used to break the stone into smaller pieces that can be removed or passed. Laser lithotripsy requires the cystoscope laser to be in contact with the stone so, again, the cat must be female; the male cat's urethra is too small for a cystoscope.

Percutaneous Cystolithotomy (PCCL)

Another less invasive way to remove bladder stones is called percutaneous cystolithotomy (PCCL). In this procedure, your cat t is under anesthesia and veterinary internal medicine specialist makes a small incision over the bladder. They insert a small tube (trochar) and a tiny camera (cystoscope) to look inside the bladder and urethra and then remove any stones. This can be done for both male and female cats.

Voiding Urohydropropulsion

This technique can work if the stones are small enough to pass through the patient's urethra. The patient is sedated, the bladder is distended with fluid, agitated, and manually expressed under pressure. By positioning the sedated patient vertically, gravity "loads" the stones in the neck of the bladder, positioned for expulsion. When the bladder is expressed, oftentimes stones can be passed that might otherwise have stayed in the bladder. Larger stones cannot be passed using this technique, and it is almost impossible to get a stone to pass this way in a male cat.

Using a diet to dissolve a calcium oxalate stone is not possible.

Once a stone has been retrieved, it can be submitted to the laboratory for analysis. After it is confirmed as calcium oxalate, the goal is to prevent future stones.

Stone Prevention

Retrieving the stones is generally the easy part of managing calcium oxalate stones. Preventing future stones is more challenging. If the patient is one of the 35% with elevated blood calcium, then steps to control the calcium level and determine why it is high should be taken. (See hypercalcemia). If blood calcium levels are normal, the following step-by-step regimen is recommended:

Step one: Feed a non-acidifying diet that minimizes calcium oxalates in the urine

Such diets use a normal calcium content, a moderate magnesium content, and citrate to bind urinary calcium. Your veterinarian can recommend an appropriate therapeutic food.

A canned diet is preferred over dry food due to its high water content. Part of the goal is to create dilute urine, and the extra water consumption is helpful. Meal feeding rather than free feeding may also be helpful in maintaining the desired urinary pH.

Avoid supplementation with vitamin C. Vitamin C is converted to oxalic acid, which modifies into oxalate. Be careful of pet vitamin supplements.

In two to four weeks, perform a urinalysis to see if there are calcium oxalate crystals (there should not be), if the urine is dilute (the specific gravity of the urine should be less than 1.030), and if the urine pH is alkaline (it should be 6.8-7.5).

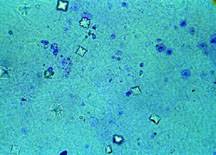

Calcium Oxalate Crystal

Oxalate crystals are classically marked with an X when viewed under a microscope) A . Public Domain Image from NASA/JSC

If the urinary pH is less than 6.5, the urine is too acidic, and potassium citrate must be given as a supplement, either as a chewable tablet, capsule, or oral liquid.

Step two: Correcting problems in the first urinalysis

If the urine specific gravity is > 1.030, this means that the urine is not adequately diluted.

The cat will need to drink more water. This is best accomplished by increasing the percentage of canned food in the diet, though other options might include using a fountain to encourage drinking or Purina Hydra Care® (a supplement added to drinking water).

Another urinalysis is performed in two to four weeks.

Step three: If oxalate crystals are present, the urine is not dilute, or if the pH of the urine is less than 7.5, the following steps are taken:

A thiazide diuretic is added to dilute the urine and correct the necessary electrolyte balance in the urine. Vitamin B6 is supplemented. A population of cats has been identified for which a B6 deficiency leads to oxalate stone development. This may or may not be helpful but is worth trying. The vitamin B6 deficiency leads to an increase in blood oxalic acid, which in turn leads to an increase in urine oxalates. A different food may need to be selected.

Once a urinalysis with the appropriate values is obtained, the patient is rechecked every three to six months with a urinalysis and every six to 12 months for radiographs. In females, stones may be identified when they are still small enough to be induced to pass naturally. A male cat will require surgery to remove stones as the male tract is invariably too small for stones to pass.

View the full recommendations of the University of Minnesota Veterinary Stone Lab.