Graphic by MarVistaVet

What is Cholangitis and is it Different from Cholangiohepatitis?

The word cholangiohepatitis breaks down into “chol” (bile), “angio” (vessel), hepat (liver), and “itis” (inflammation). Putting this all together means inflammation of the liver and bile ducts. Recently, it has been determined that the term cholangiohepatitis should probably be replaced by cholangitis because, in cats, inflammation in the liver itself, separate from the bile system is not consistently found. Still, the term cholangiohepatitis has been used for years and will probably continue to be used. Your veterinarian may use either or both terms interchangeably.

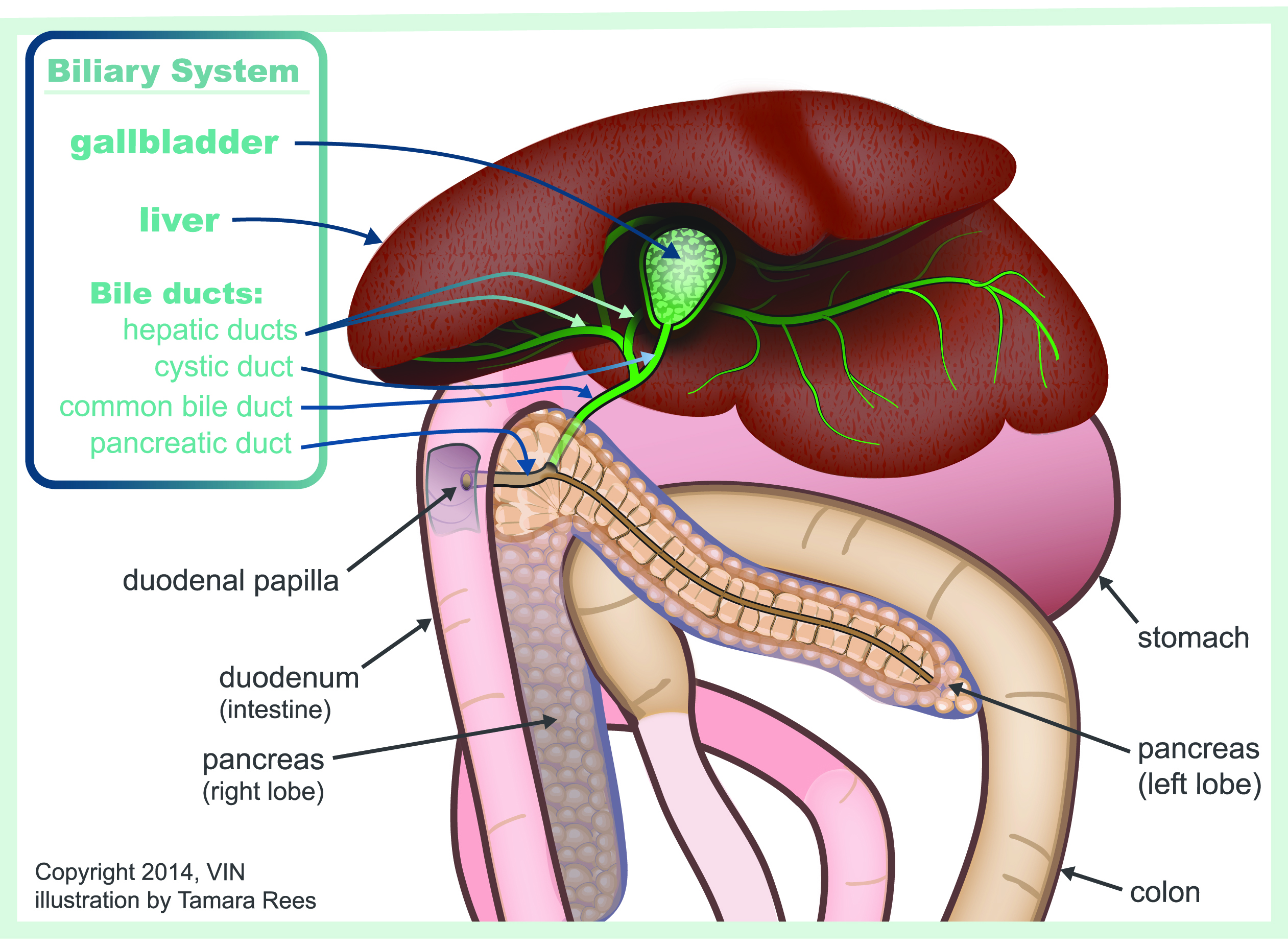

You have probably heard of bile ducts but may not really be sure what bile is all about. Bile is a greenish material the liver makes and transports to the gall bladder via small bile ducts. The gall bladder is a small greenish sac about the size of a superball where bile is stored. When the appropriate hormonal signals are present, the gall bladder contracts and squirts bile into the small intestine via one very large duct called the common bile duct.

Bile has several functions. It emulsifies the fat in our diets so that we can absorb it into our bodies. It also serves as a medium to bind toxins that the liver has processed so they can be expelled into the intestine and defecated away.

This system is fine but problems can occur when the bacteria living in the small intestine venture up the bile duct and invade the liver, which is normally sterile (free of bacteria). Inflammation results and the liver can fail. This kind of bile duct inflammation is what cholangitis is.

What is the Connection Between Cholangitis, Inflammatory Bowel Disease, and Pancreatitis?

Biliary_System

In one study, 80 percent of cats with cholangiohepatitis also had inflammatory bowel disease and 50 percent also had pancreatitis. Feline anatomy is a little different from that in other species. In cats, the pancreatic duct, which delivers digestive enzymes to the intestine, opens into the same pore as the common bile duct. This means that if bacteria invade the doorway, both the liver and pancreas are at risk for infection. In other species, each duct has a separate opening.

Inflammatory bowel disease involves infiltration of the intestinal lining with cells of inflammation. Absorption of nutrients becomes altered which in turn alters the populations of bacteria living in the intestine. An overgrowth of bacteria can occur or more aggressive species of bacteria can take over the area. It is easy to see how the bile duct can become invaded.

This combination of cholangitis (particularly the acute neutrophilic form), inflammatory bowel disease, and pancreatitis is often referred to as triaditis. Often, the patient does not recover until all three conditions are addressed.

The World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) organized a classification system for liver disease and defined several categories of cholangitis:

- Neutrophilic (sometimes called suppurative) cholangitis (either acute or chronic)

- Lymphocytic cholangitis

- Destructive cholangitis

- Chronic cholangitis (associated with infection by creatures called liver flukes that is common in tropical areas but rare in other places).

A liver biopsy can generally distinguish all of these conditions.

Neutrophilic Cholangitis and Triaditis

The average cat with this condition is a young adult male with a fairly sudden onset of vomiting, diarrhea, appetite loss, and listlessness. Often there is a fever and abdominal pain. Blood tests are typical of inflammation and liver disease with elevated liver enzymes, white blood cell count, and bilirubin. Ultrasound often shows distended bile ducts and sometimes small gallstones.

Treatment

A cat with liver failure will require hospitalization, fluid therapy, and some kind of nutritional support (tube feeding, syringe feeding of a liquid diet, or whatever is necessary) regardless of the cause of the liver disease.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are helpful in any liver failure case as they help reduce the intestinal bacterial populations (any noxious substances they produce are normally detoxified by the healthy liver, but a sick liver will not be so efficient). Antibiotics also clear the liver of invading bacteria, which is what cholangitis is all about. If possible, the gall bladder should be cultured before starting antibiotics so that the correct antibiotic can be selected.

Choleretics

A choleretic is a medication that makes bile more liquid so that it can flow smoothly without sludging. The flow of bile in the proper direction helps remove not only the toxins the liver is trying to remove in bile but also helps prevent bacteria from swimming upstream towards the liver tissue. The chief choleretic prescribed for animals is Ursodiol. A cat may well be on this medication for life after an episode of cholangiohepatitis.

SAMe

This nutritional medicine has gained tremendous popularity in therapy for all liver diseases and should probably not be left out here. SAMe stands for S-adenosylmethionine. It has several desirable functions but mostly it is an antioxidant, protecting the sick liver cells from the toxins they have absorbed and normally would be excreted in bile.

Silymarin

This is the active ingredient in the herbal medication commonly known as milk thistle. It has been shown to be protective to the liver in Amanita mushroom poisoning and many have extrapolated that it should be protective of the liver in other toxic scenarios. It is prescribed for cats with cholangiohepatitis.

Most cats begin to show great improvement within one week of beginning proper therapy.

Lymphocytic Cholangitis

In time, the acute disease described above will progress into a chronic disease that is called lymphocytic-plasmacytic cholangitis. Scarring begins to complicate the disease. Affected cats tend to be older than those with acute disease and tend to show a more waxing/waning disease course over time. Treatment is similar to what is described above, except that immune suppression/anti-inflammatory medication is needed to control the inflammation and minimize the scarring. Often, medication is needed indefinitely or long-term.

Immune Suppression

This may seem counterproductive for a condition that involves a bacterial infection, but some patients simply cannot get better until their immune system is suppressed. Why is this? For many cats, the problem started with inflammatory bowel disease: infiltration of the intestinal lining with inflammatory cells. Immune suppression is the cornerstone of therapy for this condition. Once the immune reaction is suppressed, the lining of the GI tract regains normal thickness and function, the bacterial bloom subsides, and the invasion of the liver and pancreas ceases. In some cases, immune suppression is simply needed to relieve the inflammation inherent to cholangiohepatitis. Typical medications include prednisone (or prednisolone depending on how severe the liver failure is). More aggressively, chlorambucil, a chemotherapy drug, or cyclosporine, an immune modulator, can be used.

Lymphocytic Cholangitis

This version of cholangitis is the most chronic, often having been present for years, and involves the heaviest scarring. Persian cats seem predisposed and gamma globulins are almost always highly elevated on the initial blood tests. There is usually no fever and the age group is generally atypical of feline infectious peritonitis, the other condition that commonly causes liver failure and elevated gamma globulins.

Treatment is largely the same for chronic neutrophilic cholangitis.

Overall, cholangiohepatitis is one of the more treatable liver conditions in cats. This does not mean that every cat will recover; some cats are quite advanced by the time they are first seen by the veterinarian. Pancreatitis can represent a lethal complication, depending on severity, and lipidosis can occur secondary to cholangitis, creating a more complicated disease picture. The cat that survives the acute episode can expect weeks to months of medication administration and the possibility of relapse or flare-up. The owner should become familiar with inflammatory bowel disease and pancreatitis as well.

Destructive Cholangitis

This form of cholangitis is a more extreme type of lymphocytic cholangitis in which the liver is completely infiltrated with lymphocytes and there is scarring. When the disease has gotten this extreme, it has become quite difficult to treat. At this point, bile ducts have been destroyed, and the entire liver may be involved. A chemotherapy protocol using methotrexate has been proposed by Cornell University.

Chronic Cholangitis Associated with Liver Flukes

A fluke is a disgusting creature similar to a worm. There are numerous parasitic flukes that can infect cats.

Platynosomum flukes

Fluke eggs are consumed by land snails. The snails shed embryonic baby flukes in their snail poop. A crustacean (like crayfish or similar shelled water creature) will eat the baby fluke. A lizard will eat the crustacean and a cat will eat the lizard. This infection has been referred to as lizard poisoning for this reason. In tropical areas, up to 80 percent of free-roaming cats can be infected.

Opisthochiidae flukes

Fluke eggs are consumed by water snails who shed embryonic baby flukes into the water. The young flukes attack certain types of fish, penetrate the fish skin, and continue their growth inside the fish. Cats (and potentially people) become infected by eating raw or undercooked fish.

Inside the cat's body, flukes live inside the gall bladder, creating inflammation and disease. How sick the cat becomes depends on how many flukes there are and how much inflammation is generated.

Treatment - Flukes

The good news is that flukes are killed by praziquantel, the same medication used to treat common tapeworm infections. Fluke-associated cholangitis is a curable disease.

How Do You Know Which Form is Present?

The first step is generally a diagnostic ultrasound to evaluate the texture of the liver and the structure of the bile duct system. The gall bladder is evaluated to see if the bile inside looks all gooey rather than fluid. The bile ducts are evaluated for dilation and whether they are twisted. The intestine and pancreas are also imaged so as to put a picture together of all three organ systems.

This may be enough information to begin therapy, but sometimes a biopsy of the liver is needed, especially if one of the more chronic forms is suspected. Once there is tissue sampled, it is easier to determine the category of cholangitis present.

Cats frequently require supportive care in the hospital until their appetite returns and nausea is controlled. Recovery depends on concurrent conditions and how severe and long-standing the cholangitis is.