What is Struvite?

Struvite is a urinary mineral composed of ammonium, phosphate, and magnesium. These three substances are common in urine and if they exist in high enough concentrations, they will bind together in the form of crystals. Struvite crystals are normally found in urine and have no significance on their own. Problems occur when these crystals combine with mucus and form a urinary plug that can cause a blockage in a male cat’s urinary tract (see feline urinary blockage) or when the crystals bind together to form a bladder stone.

Feline struvite stones. Image courtesy Dr. Joe Bartges

Struvite is also sometimes called triple phosphate, based on some early studies that had misidentified the minerals. The name has stuck, though, so you may hear this term.

Before widespread cat food reformulation in the 1980s, feline bladder stones could virtually be counted on to be struvite, as opposed to some other type of mineral. Nowadays, approximately 50% of feline bladder stones are struvite and the other 50% are calcium oxalate. The therapy for each of these stones is different so it is important to know which type of stone a cat has in order to provide proper treatment and prevention.

If Struvite Crystals are Normal, Why Do Some Cats Form Stones?

There are several factors at play here. The pH of the urine, the presence of proteins around which the crystals can aggregate, and urinary water content all are important issues. Ultimately, these factors come together to contribute to urine that is supersaturated with struvite. In dogs, infection is necessary to create a struvite bladder stone but in 95% of cats with struvite stones, no infection was involved (though sometimes the stone can lead to infection.)

Graphic courtesy of MarVistaVet

Symptoms

While bladder stones can sometimes be found incidentally while looking into another problem, most of the time they are found when the cat is showing signs of lower urinary tract disease:

- Straining to urinate

- Bloody urine

- Urinating in inappropriate locations

- Urinating small amounts frequently

These symptoms are expressed regardless of what the lower urinary tract disease is. Other lower urinary tract diseases include: idiopathic cystitis, bladder infection, bladder tumor, and more obscure issues such as healing bladder trauma. In cats showing signs of lower urinary tract disease, approximately 25% of them will have bladder stones so it is worthwhile to take a radiograph of the bladder to check. A urinalysis will be helpful in determining the type of stone and in ruling out other causes of urinary symptoms.

Treatment: Dietary Dissolution

Struvite stones can be dissolved by feeding specific diets. There are several commercial brands available and they all act by creating a bladder environment that is favorable to dissolving the struvite crystals back into the urine. In order for this treatment to work, the patient must eat the dissolution diet as the sole food. Obviously, the cat should not have a second disease that makes the stone diet inappropriate and the cat must be fed only the urinary diet and nothing else. If the cat does not like one diet, another can be selected; both dry and canned selections are available and can be mixed together though there is some thinking that the extra water that goes with a canned diet is more beneficial for stone dissolution.

A typical protocol involves radiographs every 3 to 4 weeks to confirm that the stone is actually dissolving, though some cats are able to dissolve their stones in as short a period as 7 days. If the stone does not completely dissolve, it may not be composed entirely of struvite (calcium oxalate stones will not dissolve with diet) or there may be some other reason why the stone is not dissolving (the cat is sneaking food elsewhere, etc.). On average, it takes about 6 weeks for a stone to dissolve. If the stone does not seem to be dissolving after a reasonable time, it may require surgical removal. If the stone is successfully dissolved, a preventive diet will be needed to prevent new stones from forming.

Treatment: Surgery

Surgery to remove a bladder stone is called a cystotomy. Here, the bladder is opened and the stones inside are simply removed. The bladder and belly are closed up and the cat is able to go home when there is a good appetite and normal urination. Some blood in the urine can be expected for several days after surgery and there may be some urinary discomfort for the first several days that necessitate pain medication.

After surgery, the stones are generally sent to a specific laboratory for analysis to confirm the stone type.

Other Methods of Stone Retrieval

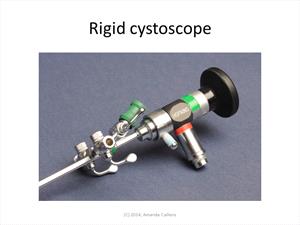

Rigid Cystoscope

Photo Courtesy Amanda Callens, BS, LVT

Cystoscopy

A less invasive method involves using a cystoscope in one of two ways. A cystoscope is a long, skinny instrument with a tiny video camera that can be inserted up the urethra and into the bladder. Because cats are so small, this is only possible in female cats; the male cat's urethra is simply too small for a cystoscope.

Once inside the bladder, the scope uses a stone retrieval basket to capture small bladder stones and carry them out of the urethra when the scope is withdrawn. If the stone is too large to pass through the urethra, it can be broken apart using laser lithotripsy. Here, a laser on the cystoscope is placed in contact with the stone and the stone is broken into pieces that are small enough to either pass or be carried out in the retrieval basket.

Obviously, special equipment is required in either of these situations and there is extra expense involved. That said, the recovery time is generally faster than with conventional surgery.

Voiding Urohydropropulsion

This technique can work if the stones are small enough to pass through the patient's urethra (so female cats only). The patient is sedated, the bladder is distended with fluid, agitated, and manually expressed under pressure. By positioning the sedated patient vertically, gravity "loads" the stones in the neck of the bladder, positioned for expulsion. When the bladder is expressed, often stones can be passed that might otherwise have stayed in the bladder. Larger stones cannot be passed using this technique. Often voiding urohydropropulsion is used to collect sample stones for laboratory analysis prior to one of the other stone removal techniques since identifying the stone type is crucial to selecting the removal technique.

Prevention

To avoid forming new struvite stones it is helpful to use a diet that creates a bladder environment that is not conducive to stone formation. There are numerous such urinary formulas and sometimes the same diet that was used to dissolve the stone can simply be continued. Ideally, a canned formula is used because canned foods have extra water and that helps make more dilute urine - and dilute urine means a lower crystal concentration.

If it is not possible to feed an appropriate diet, the use of urinary acidifiers may be necessary. Your veterinarian may recommend some monitoring tests to make sure the pH and urine concentration stay in a range where struvite stones should not form.