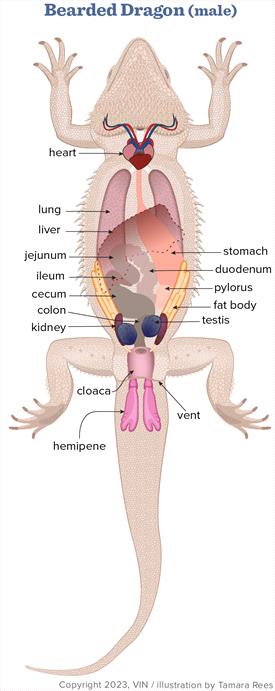

The cloaca, or vent, in reptiles, is the slit opening under the tail. The digestive tract, the reproductive system, and the bladder all empty out of the same cloacal opening.

Tissues will sometimes prolapse (slip out of place) through this opening. Cloacal prolapse refers to any condition involving tissue protruding from the reptile’s vent, where feces come out. Prolapsed tissues from the cloaca can have a variety of origins, including the gastrointestinal tract (colon, large and small intestines), urinary bladder, phallus (alligator, crocodiles, turtles, tortoises), hemipenis (snakes and lizards), and the oviduct (the organ where eggs and young are held). In rare cases, the kidneys have been known to prolapse from the vent.

bearded dragon (male) anatomical diagram

Any species of reptile can have a cloacal prolapse.

Cloacal prolapses are painful, potentially very serious, and treated as emergencies. See a veterinarian right away if you feel your pet has developed a prolapse.

Cloacal prolapses are generally caused by an excessive amount of straining from a variety of causes:

- Inappropriate humidity levels and lack of water for drinking that lead to dehydration and constipation

- Improper husbandries such as lighting, cage size, and temperature gradients

- Metabolic bone disease and lack of calcium leading to improper function of the GI tract

- Tumors or infections that lead to straining

- The phallus (in male turtles and tortoises) and hemipenis (in lizards and snakes) from impacted or infected scent glands (very similar to scent glands in dogs and cats) or from smegma plugs (a waxy, sperm-filled secretion that builds up in the hemipene and looks like a wax cast of the hemipene – no one is sure why this happens)

- Trauma from sex determination (probing)

- Oviductal prolapses in females are usually caused by failure to give birth or lay eggs (dystocia, egg binding)

- Prolapses of the colon, large intestine, and small intestines usually result from constipation or infections with parasites or bacteria.

- A bladder stone usually causes urinary bladder prolapses.

Cloacal prolapses occur in any age reptile of any species and of any sex. They are commonly seen in high-producing, egg-laying species. Risk factors include collections or individuals with husbandry deficiencies, especially low-calcium and low-mineral diets.

On physical examination, it is usually easy to determine that a reptile has a prolapse; there will be tissue protruding from the cloacal opening. The difficulty is determining what tissue is prolapsed and why. These are important questions that your veterinarian will try to answer so the proper treatment and prevention can be accomplished. Other abnormal findings that may be found on the exam are dehydration, poor body condition, and weakness.

Diagnosis

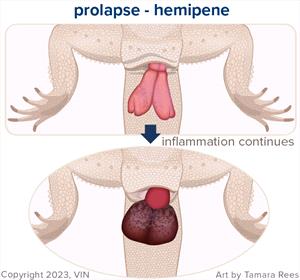

Anatomy_Bearded_Dragon_prolapse_cloaca (1).jpg - Caption. [Optional]

![Anatomy_Bearded_Dragon_prolapse_cloaca (1).jpg - Caption. [Optional] Cloacal prolapses look like a pink, round fleshy lump protruding from the cloacal opening. It may or may not have discharge. It can become very swollen over time, the longer it is prolapsed. This is an emergency situation.](/AppUtil/Image/handler.ashx?imgid=7753861&w=300&h=280)

The cloaca (present in both sexes of reptiles) may prolapse. This requires immediate attention and treatment.

The male reproductive organs (hemipene) may prolapse and become swollen. This requires immediate attention and treatment.

Your veterinarian will take a detailed diet and husbandry history and perform a physical exam. In many cases, the type of tissue (organ or part of organ, for example) that is prolapsed will be identified on sight. However, your veterinarian may want to do some additional testing to determine how the prolapse occurred. The tests suggested may include a fecal exam to look for parasites in the stool; X-rays to check for metabolic bone disease, tumors, or bladder stones; and a blood panel to look for signs of infection. Sometimes, your veterinarian may suggest advanced testing such as an endoscopy (a small camera inserted into the cloaca), an MRI, or CT scans.

Whole-body X-rays or computed tomography (CT) should be performed in most reptiles presenting with a cloacal prolapse. X-rays help rule out the presence of mineralized eggs in female reptiles, which may be associated with increased straining and potentially lead to cloacal prolapse. X-rays can also rule out the presence of uroliths (bladder stones), which can be either located in the urinary bladder or have migrated from the bladder into the cloaca. Snakes and some lizard species (e.g., bearded dragons) do not have a urinary bladder, which should be considered before evaluating these species. In addition, the GI tract can be assessed by X-rays for the presence of impactions (e.g., ingesta, sand). Poor bone quality is most likely indicative of secondary nutritional hyperparathyroidism (too much parathyroid hormone), and the patient may be hypocalcemic (low blood calcium levels), which may lead to cloacal prolapse. Additional imaging techniques such as computed tomography or MRI are very useful for evaluating coelomic organs and evaluating coelomic effusion (e.g., due to yolk coelomitis). Oral contrast studies using barium or iohexol, can also be considered if advanced imaging options are unavailable.

Routine blood work is needed in cases where a metabolic or systemic underlying disease process is suspected, such as a lack of certain vitamins or minerals in the diet. A plasma biochemistry panel will help to rule out hypocalcemia, or low calcium, and impaired kidney function, amongst other abnormalities. Increased calcium levels in female reptiles indicate reproductive activity, and therefore the cloacal prolapse may be associated with reproductive tract activity or disease. A complete blood count (CBC) will help to rule out anemia due to acute blood loss (e.g., from the prolapsed cloacal tissue) or due to chronic disease, as well as evaluate for a systemic inflammatory response. An increase in the total white blood cell count and morphological changes in the granulocytes support the diagnosis of an inflammatory process or infection.

Fecal parasitology (usually looking for parasitic intestinal worms or other microorganisms) should be performed in most reptiles diagnosed with cloacal prolapses, particularly in animals with intestinal prolapses. Large amounts of parasites can lead to enteritis, diarrhea, straining, and ultimately cloacal prolapse. Therefore, fecal samples should be evaluated as a wet-mount preparation as well as flotation. If a fecal sample is not readily available, then an enema may promote defecation. Your veterinarian may recommend antiparasitic treatment if a fecal sample cannot be obtained and internal parasites are a likely underlying cause.

Saline-infusion cloacoscopy/endoscopy under sedation or general anesthesia is the most valuable diagnostic tool to evaluate cloacal prolapse cases. For this procedure, a rigid endoscope is most commonly used and allows for the evaluation of the normal cloacal structures and the origin of the cloacal prolapse.

Treatment

Prolapses are generally treated as emergencies. Treatment should begin as soon as possible. Your veterinarian will likely instruct you to protect the protruding tissue by wrapping it in a clean, moist, and soft cloth such as a towel while on your way into the clinic in order to try and avoid any further drying or damage to the tissues.

Once the type of tissue protruding is identified, your veterinarian will attempt to replace the tissue back into its normal location and position. The tissue will be cleaned and lubricated, and gently massaged back into the cloaca, often using a cotton-tipped applicator. If the tissue is swollen, your veterinarian may use a concentrated sugar solution or gentle pressure to help reduce the size of the tissue before replacing it back into the cloaca. It is common for the tissue of the phallus or hemipenes to be necrotic. If this is the case your veterinarian may want to amputate these organs. Reptiles only use the phallus and hemipenes for reproduction, not for urination, so your veterinarian may surgically remove it, and the animal can still live a healthy life.

To prevent the tissue from prolapsing again, the veterinarian may suture each side of the vent to make the opening smaller. This allows the reptile to defecate but prevents the tissue from re-prolapsing. These sutures may be left in place for three to four weeks.

Depending on the cause of the prolapse, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) may be prescribed to help with the swollen tissue. Other treatments may include husbandry changes (diet, lighting, and temperatures), surgery to prevent future prolapses (bladder stone removal, spaying, mass or tumor removal), and antibiotics for infections. It is critical to give all medications as prescribed by your veterinarian and to return for all re-check exams scheduled.

Prognosis

There is a good chance of a complete recovery if the prolapse is recent and a cause can be identified and corrected. Phallus, hemipenis, bladder, and oviduct prolapses generally are more easily corrected and treated. If the prolapse has been more than 24 hours or the tissue is damaged the chance for a cure is reduced. Prolapses that involve the colon or the large intestine are the most difficult to treat and have the least chance of a cure.

Prevention

There are many reasons that cloacal prolapses can occur, but the most common are husbandry problems, or how the reptile is housed and cared for (including substrate and enclosure choices, lighting, humidity, diet, etc.). A detailed review and discussion with your veterinarian is a great start. Any husbandry problems identified should be corrected so that future prolapses are minimized. Unfortunately, once a prolapse has occurred, there is a greater risk of another prolapse in the future.