Radiograph, or x-ray, of a broken humerus. Photo by Dr. John Daugherty

Imaging in veterinary medicine has advanced greatly since the first radiographs (x-rays) were taken of pets just decades ago. Today a multitude of imaging tests are available to help diagnose and treat diseases in our pets. These tests include radiography (x-rays), ultrasound, CT (or CAT) scans, and MRI scans. Each of these tests has its own advantages and disadvantages, and will provide the veterinarian with different information. Many of these tests are available in general veterinary practices, but some, such as CT and MRI scans, are most often performed by specialists in large referral practices or veterinary schools.

As with all tests, none of them is perfect for every situation. The following is a brief description of different types of imaging.

Radiograph/X-ray

A radiograph, commonly called an x-ray, is a black and white two-dimensional image of part of the interior of a body. An image is generated by passing radiation through a particular structure or area, such as the chest or a limb, and the image is then captured. The traditional way of recording the image is on specific x-ray film that senses how much radiation passes through the structure and reaches the film, much like photographic film captures light. The denser a tissue is (such as bone), the whiter the image is on the film. Less dense structures, such as air in the lungs, allow almost all of the x-ray energy to pass through to the film, turning that area black.

In the past 10-12 years, many practices have upgraded to digital radiography. The principles are similar, but the images are captured on a digital recording device and displayed on a computer screen. No x-ray film is used. These images are easy to store as well as to transmit to other hospitals, or to copy to send home with pet owners. Not much more than a decade ago, these systems were considered to be too expensive for most private veterinary hospitals, but they are now being used in the majority of practices. As with most technology, the cost of installing a digital system has fallen as demand for them has increased.

Regardless of whether the images are on film or digital, radiography is the most common and readily available imaging test in veterinary practice. It is used to evaluate the size and shape of organs, such as the heart and lungs, as well as to demonstrate broken bones, some foreign objects, fluid accumulations, and many more abnormalities that may aid in diagnosis. It is also the most affordable imaging test, and is most often done prior to any of the other imaging options.

Contrast Studies

There is a subcategory of x-ray studies that use contrast dyes that show up on radiographs to highlight certain structures. The most familiar of these is the barium series, in which either a liquid or a paste containing barium is given orally or by enema to a patient to highlight a part of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Because some objects do not show up on radiographs (such as plastic, cloth, toys, rubber, etc.), barium can help diagnose obstructions or blockages. Barium shows as bright white on radiographs, so if it reaches a certain point in the GI tract and stops abruptly, we can infer that there is something blocking its progress. Sometimes we can also see a foreign object outlined by the barium trying to get around it.

The reason it is called a barium “series” is because it’s necessary to take a series of x-rays at timed intervals as the barium goes through the stomach and intestines to the large intestines. The amount of time the series must be continued depends on what is found, but it can take up to 24 hours to complete in some cases, so usually the pet is hospitalized for the day. Some patients may even need to return to the hospital the next day for follow-up.

A barium study can be done in any clinic that has radiographic equipment and liquid barium. However, if the pet is vomiting so much that the barium cannot be retained in the GI tract, the test may not be useful.

Another example of a contrast study is the intravenous pyelogram (IVP) in which a dye is injected intravenously. This dye is filtered from the blood by the kidneys and excreted through the urinary tract, so a series of images is taken to show its progress through the kidneys and into the ureters and bladder. This progress can be helpful to demonstrate structural kidney diseases, ureters that are abnormally large or don’t enter the bladder in the correct place, and for certain bladder diseases.

There are other contrast studies that can be done, including cystograms, a dye placed in the bladder through the urethra by catheterization; myelography, a dye around the spinal cord; and more.

Ultrasound (Sonogram)

Unlike radiographs, no radiation is used in an ultrasound study. An ultrasound machine uses sound waves. The ultrasound waves move out from the wand and either become absorbed into organs, pass through them, or are reflected (echo) back. Depending on how many sound waves are absorbed or reflected, an image of the internal organs is formed by a sophisticated integrated computer, and the image is then displayed on a monitor. Real-time moving images are displayed, and still images can be captured as well.

Ultrasound is painless and does not require anesthesia or even sedation in most cases. For an ultrasound evaluation to be done, the pet does need to have the hair shaved from the evaluation area because it will interfere with the images.

This test is typically done after blood tests, x-rays, or a physical examination indicates a possible problem. It is useful for evaluating abdominal organs, eyes, and the reproductive system. As with people, it can be used during pregnancies. A specific ultrasound called an echocardiogram is used to visualize the heart and blood vessels as well as its valves.

Ultrasound can “see” some things that can’t be visualized on radiographs. For example, if the abdomen is filled with fluid, the organs can’t be distinguished on traditional x-rays because fluid and tissue have the same density. However, they appear quite different from each other on an ultrasound image, so we can see through the fluid. It is also useful, for the same reason, for seeing inside an organ such as the heart or liver.

On the other hand, it is not as good at seeing through air or bone, so it does not replace radiography but rather is complementary to the information we can get from radiographs. It is common to do both x-rays and ultrasound in order to get a good picture of what is going on.

Because the equipment can be expensive, not all veterinary hospitals have an ultrasound machine. However, in those cases, they can often arrange for a traveling ultrasonographer to come to the hospital. If this is not an option, then the pet can be referred to a hospital that has one. Ultrasound images are different than x-ray images, and in some cases, it may be preferable for a veterinarian who is experienced in obtaining and reading ultrasound images to do the evaluation, or in some cases, to have a board-certified veterinary radiologist do the procedure.

As with radiography, there is also a subset of ultrasound imaging tests called contrast ultrasonography in which a material that is visible to ultrasound waves is injected as the image is being watched on the screen. These procedures are usually performed by a specialist.

Computed Axial Tomography (CAT or CT Scan)

In this test, the patient is placed on a table that moves through the scanner, which sends x-ray beams through the patient from a variety of angles. Sensors then detect them and send the signals to a computer that interprets the information and displays an image that looks like a slice of the body. As the table moves slowly through the scanner, a new slice is imaged at short intervals, each one a little further back or forward from the previous slice. Because multiple images are being taken over a period of time, the pet usually is anesthetized in order to keep it from moving while going through the scanner.

These images are white, black, and various levels of gray. Depending on how dark or light the gray is, a radiologist can see how well tissue absorbs the x-ray beam, and can thus identify abnormal tissue. It can differentiate tissue and display smaller structures, such as lung nodules, better than a traditional radiograph. CT scans are helpful in a variety of areas. Some of the most common indications for a CT scan are nasal disease, brain and spinal cord disease and injury, lung disease, and urinary tract abnormalities.

CT scans are also often used to help plan for surgical removal and/or radiation therapy for tumors. There are even 3D CT reconstructions that can show a structure in a 3-dimensional manner. This reconstruction is especially useful for radiation therapy planning. Another application of 3D scan technology is relatively recent. That is the use of 3D printers to fabricate structures based on the 3D scan. For example, in dogs that have a severely damaged jaw bone from a gunshot wound or collision with a car, the damaged part can be reconstructed, sterilized, and inserted into the damaged area to replace missing or badly damaged bone.

As with the other imaging tests, there is also a subset called contrast CT in which a contrast dye is injected into the patient to highlight certain structures and make them stand out on the CT images. These are especially useful in imaging the brain and spinal cord.

Due to the high cost of the equipment, CT scans are more expensive than radiography or ultrasonography, and are usually available only in referral centers or large practices.

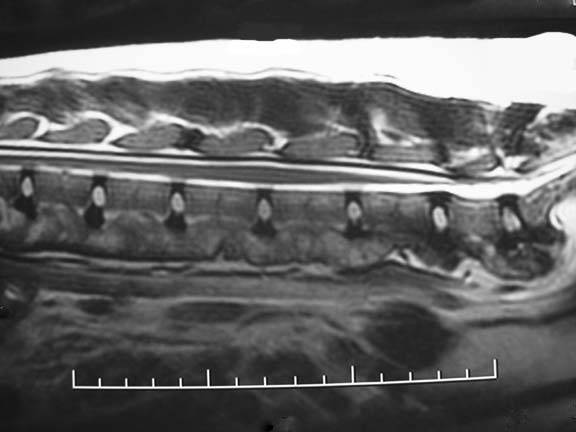

This MRI shows a dog's spine. Photo courtesy of Dr. William Blevins.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is another modality that can be extremely useful in certain patients. It uses both magnetic fields and radio waves to create images, so it is less invasive to the body than x-rays. A strong magnet – up to 40,000 times as strong as the earth’s magnetic field - briefly “magnetizes” the cells in the body while images are taken. An MRI can clearly show the interior of an organ. As with CT scans, pets are usually anesthetized because they must remain motionless.

As with CT scans, an MRI is useful for imaging certain structures, and contrast studies are used for some evaluations. Each test has its advantages and disadvantages, and the specialist performing the scan will choose one over the other depending on what exactly what is being evaluated.

Although an MRI is sometimes the only way to get a correct diagnosis, it is also the most expensive of the imaging tests currently available. There are several reasons for this, including the cost of the machine (as much as $1 million or more), as well as the cost of the facility needed to house the machine. Since it generates such powerful magnetic fields, it must be housed in a specially shielded area in order to protect the rest of the building from the magnetic waves (which can ruin computers and medical equipment in seconds). The cost of operating the equipment is also substantial. A board-certified veterinary radiologist most often reads the images.

In spite of the expense, MRI scans are now available to nearly all patients, as more and more referral facilities are using this equipment. Once thought of as an exotic test in veterinary medicine, it is now becoming quite common for pets to have an MRI scan as part of the diagnostic process.

The Future of Imaging

As technology continues to advance, new options are becoming available to veterinary patients. Among these is a growing field called interventional radiology, in which images are used not only for diagnosis, but also to target specific organs or tumors for therapy. Most of us are familiar with cardiac catheterization and angioplasty in human medicine; this is an example of interventional radiography.

In veterinary patients, there are many examples. One of the most exciting is the development of minimally invasive cancer treatments. For example, some tumors can be visualized with contrast fluoroscopy (basically a moving x-ray picture) or ultrasonography, and a catheter can be advanced directly into the blood vessels that supply the tumor while the radiologist guides it by watching the screen. Chemotherapy drugs can then be injected directly into the tumor, destroying or damaging it with much lower amounts of toxic drugs because only abnormal tissue is being targeted.

Other relatively new technologies that are becoming more commonly available include 3-D ultrasonography and tissue elastography. In 3D ultrasonography, a computer uses multiple ultrasound images and builds a realistic 3-D image from them. These images can be displayed in real-time, so that a structure can be evaluated from various angles to give a more accurate overall picture. 3D imaging is especially useful for evaluating complex cardiac structural abnormalities.

Tissue elastography can also be performed during an ultrasound study if the machine is equipped for it. Using sophisticated computer algorithms, the elasticity of a structure can be determined and displayed as a color gradient. For example, a large nodule inside the tissue of the liver could either be a tumor or a benign nodule that requires no treatment. In some cases, elastography can help to determine if a more invasive procedure, such as a biopsy, is warranted. In the past, the only way to determine if a nodule was malignant was by biopsy, and although that is still necessary to diagnose an abnormality with certainty, tissue elastography can help determine when it may be safe to wait and monitor a lesion rather than advancing to more aggressive diagnostic steps.

The advances in diagnostic imaging available to veterinarians and their patients is truly astounding. Only a few decades ago, radiography was our only option. Technology has advanced tremendously, and every year, new techniques and uses of these modalities are being developed. Veterinary patients have benefited from many of these advances, and will continue to do so in the future.