Most people have heard of leukemia and know it is a kind of cancer that people commonly get, and that it is generally a serious and often fatal disease. This article explains what leukemia is in dogs, and why it is bad; it also reviews the most common forms of leukemia for dogs, called the lymphocytic forms.

Malignant Lymphocytes

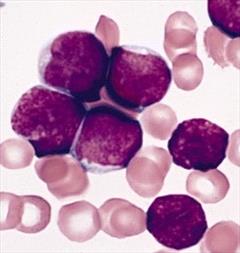

The large purple cells are circulating malignant lymphocytes. Photo courtesy of the University of Georgia

Leukemia is a word describing exactly what it is: “Leuk” means white (in this case, white blood cells), and “mia” means blood. Leukemia means “white blood” or, more specifically, an overabundance of white blood cells in the bloodstream. Now, white blood cell counts go up in response to infection, inflammation, allergy, and even stress. The patient with leukemia has an overabundance of a particular white blood cell, but in magnitudes so great that it is amazing that the change cannot be seen with the naked eye. The bloodstream is swarmed with cancerous white blood cells, and the bone marrow from whence they came is consumed with making cancer cells and making very few of the other blood cells needed to survive. In the case of lymphocytic leukemia, the cancer cells are of lymphocyte origin. However, there are many other types of leukemia, potentially one for every type of blood cell made by the bone marrow. Lymphocytic Leukemia will be discussed in this article.

What Causes Lymphocytic Leukemia?

In dogs, there is not much of a list of possibilities, though in other species, some culprits have been identified. It may be that these same factors are causes in dogs as well. In humans, radiation exposure has been linked to lymphocytic leukemia development, as has exposure to benzene. In cats, birds, and cattle, there is a “leukemia virus” (though it is not the same virus for different animals). Not surprisingly, given the name, leukemia viruses cause leukemia and other lymphocytic cancers, such as lymphoma.

Chronic Versus Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia

In most of these patients, the diagnosis of lymphocytic leukemia is clear when an impossibly high lymphocyte count is seen. A normal lymphocyte count is generally less than 3,500 cells per microliter. In lymphocytic leukemias, lymphocyte counts over 100,000 are common.

Numbers of this magnitude generally flag the sample at the reference laboratory for reading by a clinical pathologist (or if the initial testing is done in the veterinarian’s office, the lymphocyte reading will cause the sample to be submitted for further analysis). The pathologist will then visually review the slide for signs of malignancy within the cells. The diagnosis of lymphocytic leukemia is usually fairly obvious (for exceptions see below) but the key is to determine whether the lymphocytic leukemia is chronic or acute.

Normally, the term chronic means a process or disease that has been going on for a long time, and acute means that the process started suddenly. For lymphocytic leukemia, these terms have a different meaning: they refer to how mature the cancer cells look. Lymphocytes develop from precursor cells in the bone marrow or lymph nodes and undergo several stages of development before they are released into the bloodstream. When a leukemia involves earlier stages of lymphocytes, it is said to be an acute leukemia. When cells are more developed, the patient is said to have a chronic leukemia. As a general rule, the acute leukemias act more malignantly than the chronic ones. There is some controversy over whether acute or chronic lymphocytic leukemia is more common.

Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia (ALL)

Lymphoblasts Under Microscope

Patient with Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia. Photocredit: Public Domain Image from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

ALL (acute lymphocytic leukemia, also known as Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia) involves the obliteration of the bone marrow by immature lymphocytes called lymphoblasts, or simply blasts. When 30 percent of the bone marrow cell population consists of blast lymphocytes, ALL is confirmed. In 90% of patients, the blast cells spill out into the circulating blood, which can be detected in a blood sample. The lymphoblast cell is the hallmark cell of ALL.

The most common symptoms include listlessness, poor appetite, nausea, diarrhea, and weight loss. The average age at diagnosis is only 6.2 years, with 27 percent of patients being under age 4 years. Over 70 percent of patients have enlarged spleens due to cancer infiltration, over 50 percent have enlarged livers, and 40-50 percent have lymph node enlargement (though this last is not dramatic). On lab tests, over 50 percent will have anemia (red blood cell deficiency), 30-50 percent will have a platelet deficiency (platelets are blood clotting cells so deficiency can lead to spontaneous bleeding), and 65 percent have what is called neutropenia. Neutrophils are white blood cells that serve as the immune system’s first line of defense. Neutropenia is a neutrophil deficiency that leaves the patient vulnerable to infection.

Pets with ALL are generally very sick and require aggressive chemotherapy. Often, they need blood transfusions because of the severe anemia or antibiotics to make up for the neutropenia. Typical chemotherapy protocols include prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, L-asparaginase, and doxorubicin. Still, even with aggressive chemotherapy, only 30 percent of patients achieve remission, and with no therapy, most patients die within a few weeks. Prognosis is poor when ALL is diagnosed, so it is important to distinguish ALL from lymphoma or from more treatable forms of leukemia.

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

As rapid and aggressive as acute lymphocytic leukemia is, chronic lymphocytic leukemia is the opposite, with most patients having few symptoms and long survival times. The clinical course of CLL is long, lasting months to years, with the average age at diagnosis being 10 to 12 years. In up to 50 percent of cases, there are no symptoms of any kind at the time of diagnosis, and the leukemia is discovered by chance on a routine blood evaluation. In CLL, it is the sheer number of circulating cells rather than what they look like that makes the diagnosis.

There are three forms of CLL: T cell (called T-CLL), B cell (called B-CLL), and a form involving both B and T cells (called atypical CLL). T-cell and B-cell are the most common forms. T-CLL has the best prognosis overall, although many factors can affect a patient’s outcome. The type of CLL that a given patient has can be determined by blood testing (immunophenotyping or PARR testing, which stands for PCR testing for antigen receptor rearrangements), thus revealing the most information regarding prognosis and what to expect.

Because CLL progresses slowly, treatment is often forgone unless one of several conditions exists. Conditions for which treatment of CLL is recommended include lymphocyte counts are greater than 60,000; if there are symptoms or organ enlargement; hyperviscosity syndrome (more common with B-CLL, see below); or if other white blood cell lines are suppressed by the tumor. If treatment is deemed necessary, common protocols involve prednisone, chlorambucil, vincristine, and/or cyclophosphamide. Survival times of one to three years with good quality of life are common.

Golden Retrievers and German Shepherd dogs may be predisposed to CLL. Boxers, unfortunately, tend to get a more aggressive form of this condition and have much shorter survival times.

What Else Could it Be?

In most cases, the diagnosis is fairly obvious, but not always. In early cases, the lymphocyte count may not have climbed to its ultimate level, so the diagnosis may be unclear. Similarly, in late stages, the bone marrow may be so damaged that it can no longer turn out many cells at all. In these cases, tests may be needed because when lymphocytic leukemia is ambiguous, there are other diseases that must be ruled out:

- Lymphoma, in its most advanced stages, involves the bone marrow, and circulating cancerous lymphocytes spill into the bloodstream. Dramatically enlarged lymph nodes, if present, are a good indicator of lymphoma; lymphocytic leukemia patients usually have mild or no lymph node enlargement.

- Infection with the blood parasite Ehrlichia canis can lead to high lymphocyte counts and can be hard to distinguish from CLL. Special blood tests for Ehrlichia may be in order.

- Some other types of leukemia can be so poorly differentiated that special stains, PCR testing, or a type of analysis called immunophenotyping might be necessary to characterize the type of cancerous white blood cells involved.

- Acute stress can cause lymphocyte counts to be as high as 15,000 cells per microliter, but this is a temporary phenomenon.

- Hypoadrenocorticism (Addison’s disease) can lead to a lymphocyte count of up to 10,000 cells per microliter.

- Chronic infection with fungus (if severe) or blood parasites can elevate lymphocyte counts dramatically.

- Lymphocyte counts of over 20,000 are almost always caused by lymphocytic leukemia.

- English bulldogs get a condition called polyclonal B cell lymphocytosis, which is not a type of cancer but can look a lot like CLL and sometimes requires similar treatment.

What is a Monoclonal Gammopathy? What is Hyperviscosity Syndrome?

The word "gammopathy" means an abnormal process is occurring, and lots of gamma globulins are present. So, what are gamma globulins? Gamma globulins are a class of blood proteins that include antibodies. What are antibodies? They are special proteins made by the immune system to coat and attack organisms invading the body.

Lymphocytes produce antibodies. Infection activates the lymphocytes, and they start proliferating and making antibodies. Each lymphocyte spawns many daughter lymphocytes, and all the daughter lymphocytes make the same antibody. Because many lymphocytes are stimulated, many different types of antibodies are produced. This translates into lots of different antibodies and a high gamma globulin level. This situation is called a "polyclonal gammopathy" because many lymphocytes are stimulated and proliferate, and different antibodies are made.

When leukemia occurs, only one lymphocyte line proliferates: the cancerous one. If this line of cancerous lymphocytes starts producing antibodies, only one type of antibody results. In reference to the spectacular number of lymphocytes that comprise leukemia, all producing antibodies, you can imagine how many antibodies are produced. Because all the antibodies came from one single lymphocyte line, this condition would be called a "monoclonal gammopathy."

The reason why monoclonal gammopathy is bad because it can cause hyperviscosity syndrome. Antibodies are blood proteins, and if enough blood protein is circulated, the blood thickens. Smaller blood vessels are too delicate to circulate thickened blood. They break and bleeding results. The symptoms that occur depend on where these small vessels bleed. There could be nose bleeds, seizures, blurred vision, or even blindness.

There are only a few conditions that can cause a monoclonal gammopathy.

- Ehrlichia infection (the only non-tumorous cause)

- Lymphoma

- Plasma Cell Cancer (“multiple myeloma”)

- B Cell Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Lymphocytic leukemia is a cancer that not all veterinarians are comfortable treating. Discuss with your veterinarian whether a referral to a specialist would be best for you and your pet.

In Summary:

- Leukemia is a great overabundance of a particular white blood cell in the bloodstream.

- These cancer cells are from lymph, the fluid containing infection-fighting white blood cells.

- We don’t know what causes it in dogs.

- The diagnosis is clear when an impossibly high lymphocyte count is seen. A normal count is less than 3,500 cells per microliter; in lymphocytic leukemias, counts over 100,000 are common.

- The normal meaning of acute and chronic does not apply here. When the cancer cells look like immature/poorly developed white blood cells, the lymphocytic leukemia is called acute. When the cancer cells are more developed (look like mature white blood cells), the patient has chronic leukemia.

- The diagnosis is usually fairly obvious but not always: it can depend on the how far along the disease is; it could be caused by something else, such as the blood parasite Ehrlichia canis; Addison’s disease; another type of leukemia; another cancer type, such as lymphoma; a severe, chronic fungal infection; and more. However, lymphocyte counts over 20,000 are almost always from a lymphocytic leukemia.

- Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) obliterates bone marrow with immature lymphocytes called lymphoblasts, or simply blasts. The lymphoblast cell is the hallmark of ALL.

- Prognosis is poor for ALL, so it should be distinguished from lymphoma or more treatable forms of leukemia.

- Signs of ALL: listlessness, poor appetite, nausea, diarrhea, and weight loss. The average age at diagnosis is 6.2 years, with 27% under 4. Over 70% have enlarged spleens, over 50% have enlarged livers, and 40-50% have enlarged lymph nodes.

- Pets with ALL are generally quite sick and require aggressive chemotherapy and often blood transfusions.

- Even with aggressive chemotherapy, only 30% of ALL patients go into remission, and with no therapy, most patients die within a few weeks.

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the opposite of ALL, and most patients have long survival times.

- It lasts months to years. The average age at diagnosis is 10-12 years.

- In up to 50% of cases there are no symptoms at diagnosis; it is often discovered on routine blood tests.

- In CLL, it is the sheer number of circulating cells rather than what those cells look like that makes the diagnosis.

- Because CLL progresses slowly, treatment is often not given unless one of several conditions exist, such as especially high lymphocyte counts; symptoms or organ enlargement; hyperviscosity syndrome; or if other white blood cell lines are suppressed.

- If treatment for CLL is necessary, common protocols involve prednisone, chlorambucil, vincristine, and/or cyclophosphamide.

- There are three forms of CLL: T cell (called T-CLL), B cell (called B-CLL), and a form with both (called atypical CLL). T-cell and B-cell are the most common forms. T-CLL has the best prognosis overall, although many factors can affect a patient’s outcome. The type of CLL can be determined by blood tests.

- Survival times of 1-3 years with good life quality are common.

- Boxers tend to get a more aggressive form and have shorter survival times.

Back to top