normal canine hip

What is Hip Dysplasia?

Hip dysplasia occurs in many species (including humans and cats) but is mainly a concern in dogs. It can occur in any breed or size of the dog but is more common and tends to be a bigger issue in larger breeds.

An Overview

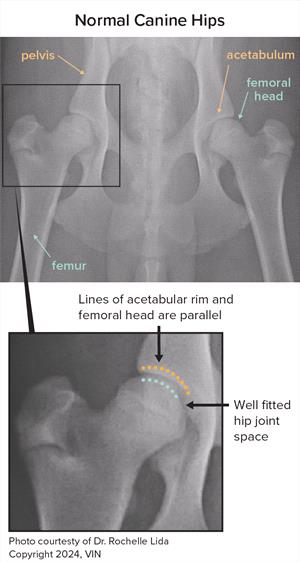

The hip is the ball and socket joint that connects the hind limb to the pelvis. The femur is the thigh bone. The ball is called the femoral head, and the socket in the pelvis is the acetabulum.

The ball and socket grow in concert with one another in the normal hip joint. The ball sits deeply in the socket and rotates within. The ball and socket are held together by a ligament (a band of tough tissue between the bones), a joint capsule (which also contains joint or synovial fluid), and muscles that connect the pelvis to the femur. Articular cartilage (joint) lines the ball and socket.

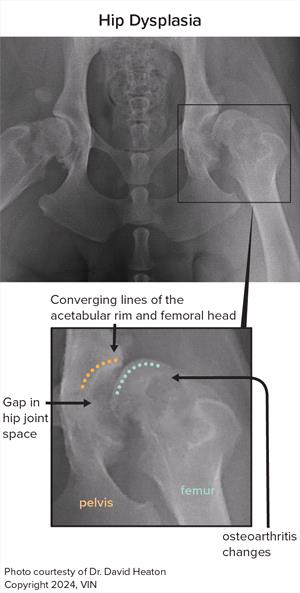

In a hip with dysplasia (dysplasia meaning abnormal growth and development), the connection between the ball and socket becomes looser than what is considered normal. This results in abnormal movement of the ball in and out of the socket in addition to the regular rotation, and the shape and depth of the socket or the shape of the femoral head may also be altered.

A scale is used to rate a hip’s condition, with “more normal” on one end of the spectrum and “more dysplastic” on the other. The higher the rating is on the dysplastic side, the more likely the dog will show abnormal movement as they walk or run.

Healthy joint cartilage and proper lubrication by joint fluids result in a nearly frictionless and smooth motion. Abnormal hip movement affects hip function, tiring the muscles surrounding the hip as the dog moves or engages in activity. This abnormal motion eventually wears down the joint cartilage and can result in permanent damage with loss of smooth function.

Damaged joint cartilage does not repair well, and further changes to cartilage and bone occur as the process continues. These changes and the resultant bone-on-bone rubbing from the loss of cartilage can cause pain. This process of cartilage damage, loss, and changes to the joint capsule and bones is termed osteoarthritis (“OA”) or degenerative joint disease (“DJD”).

Signs of Hip Dysplasia in Younger Dogs

Signs of hip dysplasia may be observed in puppies before one year of age. Most of these signs will be mechanical lameness, although some may also have early symptoms of arthritis.

In some dogs, signs of mechanical lameness may seem to disappear around one year of age until about two to four years of age, when osteoarthritis progresses and symptoms recur.

However, many dogs with hip dysplasia never have recognizable signs or only display such signs when they are older.

In younger dogs, the signs of hip dysplasia include:

- Slowness to rise from a sitting or lying position

- Trouble or disinterest in prolonged play with other animals

- Tiring easily on walks and needing to sit and rest

- Sashaying/wiggling gait with the hind limbs

- Trouble with stairs or jumping into vehicles

Puppies with dysplasia may “bunny hop” with the two hind limbs together when running or climbing stairs.

Before OA sets in, young dogs might not be in obvious pain except for some muscle soreness. The signs often do not respond much to analgesics (pain medications) or anti-inflammatory medications.

An owner might notice poor muscle development in the dog’s hind limbs or notice the hip bones seem more pronounced. This is due to poor muscle mass around the point of the hips.

Sometimes, an obvious “pop” from the hip area can be heard or felt as the dog moves because the ball is moving inappropriately in and out of the socket.

Arthritis and Signs of Hip Dysplasia in Older Dogs

FIXEDcanine_hip_dysplasia_cms_resizeto_320x600 (2)

Even in “normal” joints, arthritis can be a part of aging, but if a dog has dysplasia, arthritis can develop much sooner than it might in a dog without the condition. The signs of pain and limping or lameness are more likely when arthritis is present.

As arthritis progresses, pain may start to increase. Signs of arthritis pain, in addition to some of those signs described above with mechanical lameness, can be:

- Limping

- Reluctance to move

- Sensitivity to handling or when the rear end is touching

- Vocalizing (whining, crying)

- Behavioral changes (lower tolerance for contact with humans and other animals)

Arthritis pain is more responsive to anti-inflammatory and pain medications than mechanical lameness alone. Your dog’s lifestyle can affect the degree of pain. Working dogs may exhibit more pain than less active house pets.

Thigh muscle atrophy (loss of muscle mass) may be noticed as the dog bears less weight on the affected limb.

What Causes Hip Dysplasia?

Hip dysplasia results from a combination of genetic makeup and environmental factors. A veterinarian relies on tests of a dog’s phenotype to decide where the dog’s hips are on the spectrum of more normal or more dysplastic. Phenotype is the result of genotype (the genetic makeup inherited from the parents) and environmental factors, such as diet and hormones. Since hip dysplasia is felt to be mostly due to underlying genes and less to environmental influence, assessment of phenotype gives a decent view of a dog’s genetic “load”.

However, genes and hereditary traits don’t always show up in every animal, and even if hips fall into the more ”normal” range for phenotype, the genes for hip dysplasia may still be carried and passed on to future generations.

Thus, dogs with “normal” hips and “normal” pedigrees may yet produce puppies with the condition.

Hip dysplasia is considered to be a “developmental” disease rather than congenital (a disease present at birth), so a dog can have “normal” hips at a younger age and then develop the condition or have the condition worsen later in life. About 95% of dogs with hip dysplasia will have detectable evidence by the time they are two years old, although they may or may not have or develop signs.

Diagnostics/Testing

Palpation

In young dogs, the veterinarian may perform an Ortolani test. This involves palpation (manipulation) to look for abnormal movement of the ball and socket joints. More normal hips would lack the loose movement of hip dysplasia. This test is not always accurate, unfortunately. Not every veterinarian is skilled at performing the test. Some dogs with severe hip dysplasia may either have a very shallow socket and/or a femoral head so far out of the socket that it can no longer be moved in and out, resulting in a “negative” test. Older dogs may have changes in the bones and joint capsule, resulting in a negative Ortolani test.

Palpation at any age also includes checking the range of motion in the hips, and feeling for grinding caused by bone-on-bone rubbing, or bone spurs that develop as part of the osteoarthritis process.

X-rays

X-rays are done for screening in working dogs, dogs intended for an athletic lifestyle, dogs meant for breeding, or done as part of an examination when hip dysplasia is suspected as a cause of hind end pain or lameness.

Various techniques for X-raying hips have been developed, and all require sedation to be done properly.

Certifications

Dogs meant for careers as working or breeding animals will most likely require certifying evaluations related to conditions common in their breed.

There are organizations that give ratings for hip dysplasia:

OFA

The Orthopedic Foundation for Animals has been around for many decades, and board-certified radiologists assign their scores. These results are somewhat subjective. Although OFA can screen dogs of any age, they will not certify a dog as free of hip dysplasia unless the dog is at least 24 months old. This can be disadvantageous since owners would like to know sooner if a dog is suitable for its upcoming breeding or working career.

The X-ray positioning needed for OFA certification can also cause results to be misjudged, usually by missing some dogs who have hip dysplasia and calling them normal. However, despite these shortcomings, the OFA screening test is still the one most familiar to breeders.

PennHip

An alternative and increasingly popular technique developed at the University of Pennsylvania, this test includes the same X-ray used by OFA but also two additional views. It mimics the Ortolani test (mentioned above), giving a graphic and measurable demonstration of the laxity (slackness) in the hips.

PennHip measurements can be done as early as four months of age and compare results obtained for that particular breed. Because actual measurements are used, PennHip is more objective than OFA. Rather than certifying dogs as “normal” or describing them as “dysplastic” (as with OFA results), PennHip recommends limiting breeding to those dogs in the best half of hip scores for that breed.

Breeders can choose to be more conservative if they wish. For puppies intended for working careers, the results of PennHip will help guide which ones are more suitable and which might be less suitable. Drawbacks to the PennHip method are that only veterinarians trained and certified can perform the test, and it costs a bit more than OFA.

As noted above, X-ray screening at an early age makes sense for puppies intended for breeding later in life or those that are intended for athletic working careers. For the average pet dog, there may be less value to such screening because neither the presence of laxity nor even the finding of osteoarthritis can accurately predict whether the dog will have symptoms of hip dysplasia in the future, and if so, how severe those symptoms might be.

On the other hand, knowing that a puppy has hip dysplasia might put the veterinarian and owner “on alert” for possible signs to watch for, or lead to a consultation with an orthopedic surgeon for additional guidance.

Owners should discuss with their veterinarian whether to do routine screening (often done at the same time a dog is anesthetized for castration or spay surgery, but sometimes even sooner) based on the intended use of the dog and any other concerns. X-rays are always a suitable diagnostic test for dogs with hind-end lameness or signs of hip pain.

The caution here is that the mere presence of hip dysplasia and/or arthritis – regardless of how bad the hips may look on an X-ray – is not conclusive for blaming hind end lameness or pain on the hips unless all other potential causes have been ruled out. Even if some X-rays taken earlier in life showed that a dog was dysplastic, this does not prove that any new lameness or pain in the hind end is due to the hips.

Neither owners nor veterinarians should have “tunnel vision” and assume that hind limb lameness is due to hip dysplasia, regardless of how severe any such dysplasia seems on X-rays.

Please see: Hip Dysplasia in Dogs - Prevention and Treatment