There are two species of roundworms that affect cats and kittens: Toxocara cati and Toxascaris leonine, with Toxocara cati (cats only), felt to be the more harmful species, and Toxocara cati (cats only). Toxascaris leonina affects both dogs and cats. Medications for "roundworms" will cover both species, but since the latter parasite can be shared with dogs, it is helpful to know which pets need to be covered in the event of infection.

How Do You Know There Are Worms If You Can't See Them?

People often expect to see worms if they are present, but this generally only holds for tapeworms. Some pets will actually vomit up a roundworm or pass one, but most of the time, roundworms will be inside their host's body and must be found with some kind of fecal testing. Testing might proceed either in the process of investigating an upset stomach or simply on a routine test.

How Infection Occurs

Photo by CDC & Alaska State Public Health Library

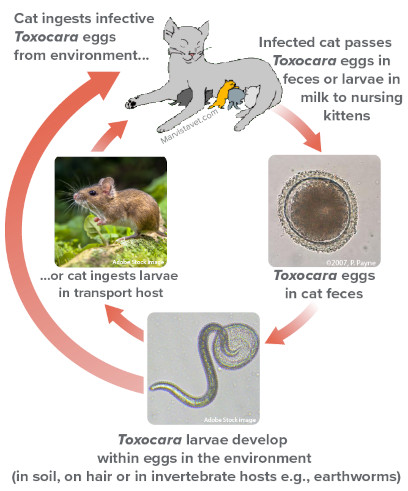

In cats, there are three ways by which infection with Toxocara cati occurs:

- Consuming infective worm eggs from soil in the environment (generally through normal licking of dirty paws).

- Nursing from a mother cat that was herself infected in late pregnancy; most kittens are infected this way.

- Consuming a prey animal – usually a rodent - that is carrying developing worms.

Note: Dogs cannot be infected with Toxocara cati. They have their own roundworm called Toxocara canis.

Why Is Infection Bad?

Roundworm infection can have numerous negative effects. It is a common cause of diarrhea in young animals and can cause vomiting as well. Sometimes the worms themselves are vomited up, which can be alarming as they can be quite large, with females reaching lengths of up to seven inches. The worms consume the host’s food and can lead to unthriftiness and a classic pot-bellied appearance. Very heavy infections can lead to pneumonia as the worms migrate through the body, including the lungs, and if there are enough worms, the intestine can actually become blocked with a wad of worms.

Human infection by this parasite is especially serious (see below). To reduce the exposure hazard to humans and other animals, it is important to minimize the contamination of environmental soil with the feces of infected animals. A classical source of infection is a child's outdoor sandbox, in which outdoor cats may defecate.

Life as a Roundworm

Toxocara cati has one of the most amazing life cycles in the animal kingdom. Understanding how roundworms develop from eggs to adults will help ensure that you maintain a proper deworming schedule and that your roundworm control plans make sense. Let us begin at the beginning with the egg.

Step One: The Worm Egg Develops an Embryo

Toxocara eggs are passed in the host’s feces. If a fecal sample is tested, the eggs can be detected, and a roundworm infection can be confirmed. The baby worm develops in the outdoor world inside its microscopic egg for two to four weeks before it infects a new host. During those two to four weeks, the original feces melt into the local dirt, carrying the egg and baby with it. The baby is protected by the egg, which is very tough and able to withstand all sorts of weather changes and temperatures. After the two four-week incubation, the egg is basically part of the local dirt and completely invisible, but the baby inside is ready for a host and will sit there inside its egg waiting.

Fresh feces are NOT infectious to cats, but dirt can be. It takes a month before the worm embryo becomes infective. During this time, visible fecal matter has melted into the soil, and the soil/dirt has the infectious eggs.

Step Two: The Worm Enters the Cat

The egg, containing what is called a second-stage larva, is picked up orally by a cat or by some other animal. The egg hatches in the new host’s intestinal tract, and the young worm burrows its way out of the intestinal tract to encyst in the host’s other body tissues.

If the new host is a cat, the body migration continues. If the new host is a member of another species, such as a rodent, the worm larvae just sit around in the body tissues where they encyst. They don't migrate and don't develop further unless their accidental host comes to be eaten by a cat. Their goal is to get inside a cat one way or the other. These prey animals that carry worm larvae are called paratenic or transport hosts. The cat is called the definitive host.

Step Three: The Young Worm Migrates Through The Cat's Body

At this point, the second-stage larva has entered the cat's body and broken out of the intestinal tract. Some larvae simply migrate to the nearby liver and encyst there. Others move to the mammary gland (see later), but the majority will head for the cat's lungs and will have made it to the lungs within three days of entering the cat. Once they reach the lung, they develop into third-stage larvae and burrow into the small airways, ultimately traveling upward toward the host’s throat. A heavy infection can produce a serious pneumonia. When they get to the upper airways, the cat starts coughing. The worms are coughed up into the host’s throat, where they are swallowed, thus entering the intestinal tract for the second time in their development.

Graphic courtesy of MarVistaVet

If the host is a nursing mother, second-stage larvae can migrate to the mammary gland instead of the lung. Kittens can thus be infected by drinking their mother’s milk. Larvae that had encysted in the liver and gone dormant will re-awaken during the host's pregnancy, continuing their migration just in time to infect the nursing kittens. In this way, a well-dewormed mother cat can still find herself infecting her kittens.

When cats are dewormed, only worms in the intestinal tract are affected. It does not affect encysted larvae. It is difficult to prevent mother-to-kitten transmission, and routine deworming is inadequate.

Step Four: Worms Mate and Lay Eggs of Their Own

The young worms returning to the feline intestinal tract are almost grown up. They are called "fourth-stage larvae" and very quickly mature to adulthood and begin to mate. Their first eggs can be detected in host feces approximately four to five weeks from the time the egg and its baby are first consumed by the host. From here, the worm's life cycle repeats.

Toxocara_life_cycle

Graphic by VIN

Why is it Good to Know the Life Cycle?

There are some important take-home points here.

- Fresh feces are not infectious, but dirt could be.

- Cats can get roundworms from cleaning dirt off their fur.

- Cats can get roundworms from hunting.

- Mother cats readily give roundworms to nursing kittens.

- There is a whole-body worm migration, which means that all the worms in the process of migration must be killed off if the cat is to be "roundworm-free." In other words, one deworming treatment is not enough.

How Do You Know If Your Cat Is Infected?

You may not know, and this is one of the arguments in favor of regular deworming. Regular deworming is especially recommended for cats that hunt and might consume the flesh of hosts carrying worm larvae. Kittens are frequently simply assumed to be infected and automatically dewormed on a regular schedule.

Of course, there are ways to find out if your pet is infected. If a cat or kitten vomits up a worm, there is a good chance this is a roundworm (especially in a kitten). Roundworms are long, white, and described as looking like spaghetti. Tapeworms can also be vomited up, but these are flat and obviously segmented. If you are not sure what type of worm you are seeing, bring it to your vet’s office for identification.

Fecal testing for worm eggs is a must for kittens and a good idea for adult cats having their annual check-up. Obviously, if there are worms, they must be laying eggs in order to be detected, but by and large, fecal testing is a reliable method of detection.

How Do You Get Rid of Roundworms?

Numerous deworming products are effective. Some are over-the-counter, and some are prescription. Many flea control and heartworm prevention products provide monthly deworming, which is especially helpful in minimizing environmental contamination. Common active ingredients include:

- Pyrantel pamoate (active ingredient in Strongid®, Nemex®, Heartgard Plus®, Drontal®, HeartgardPlus® and others)

- Piperazine (the active ingredient in many over-the-counter products)

- Fenbendazole (active ingredient in Panacur®)

- Selamectin (the active ingredient in Revolution®)

- Emodepside (the active ingredient in Profender®)

- Moxidectin (the active ingredient in Advantage Multi®)

- Eprinomectin (the active ingredient in Centragard®)

- Milbemycin oxime (the active ingredient in Interceptor®)

Older deworming medications removed adult worms by basically “anesthetizing” them, causing them to release their grip on the pets’ intestines and be flushed out with the stool. Once outside the body, the worms would die. Most medications used today kill the adult worms while attached to the intestine, and the dead worms are expelled in the stool.

Most deworming products only kill adult worms, not the larvae. After a deworming treatment, the adult worms are cleared from the intestine, but they will be replaced by new larvae that have migrated to the intestine as a part of their life cycle. This means that a second, and sometimes even a third, deworming is needed to keep the intestine clear. The follow-up deworming is generally given several weeks following the first deworming to allow for migrating worms to arrive in the intestine, where they are vulnerable.

Do not forget your follow-up deworming.

At this time, only a certain few products can kill, in one treatment, immature worms still migrating in addition to the adults in the intestine. All other dewormers will require repeat deworming. Discuss the need for repeat treatments with your veterinarian.

The Companion Animal Parasite Council recommends that kittens be routinely dewormed at age two weeks to prevent hookworm infection. Then, the kittens should be placed on a monthly heartworm preventive that includes protection/deworming against Toxocara cati.

What About Toxascaris Leonina?

The life cycle of Toxascaris leonina is not nearly as complicated. This parasite does not migrate through the body in the way that Toxocara does. As before, the egg is passed in feces and the baby worm develops inside it. The Toxascaris egg only requires a week out in the world to become infectious. After that, it is ready to be licked by a cat. After the cat consumes the egg and baby, the egg hatches in the cat's intestine and develops into an adult worm over the next two to three months. There is no body migration and no arrested development. Once the worms are adults, they mate and produce eggs of their own.

Toxascaris leonina can infect both dogs and cats alike.

As with Toxocara cati, diarrhea can result from Toxascaris leonina and deworming is needed to control symptoms and prevent contagion.

Many of the newer deworming products are not labeled for use against Toxascaris leonina, which does not necessarily mean that they do not work, but here are the reliable classics that have been used for decades with efficacy:

- Pyrantel pamoate (active ingredient in Strongid®, Nemex®, Drontal®, Heartgard® and others)

- Piperazine (the active ingredient in many over-the-counter products)

- Fenbendazole (active ingredient in Panacur®)

Because Toxocara migrates through the body, a sequence of deworming is typically performed so as to get all the larvae that were migrating at the time of the earlier deworming. Because Toxascaris does not migrate, only one deworming should cover it. Of course, a known infection of either worm suggests a contaminated environment, which is why the Companion Animal Parasite Council recommends regular deworming for pet dogs and cats.

For More Information

The Companion Animal Parasite Council has a client education page for cat owners on parasites, including roundworms.

See more about roundworms in dogs and roundworms in people.