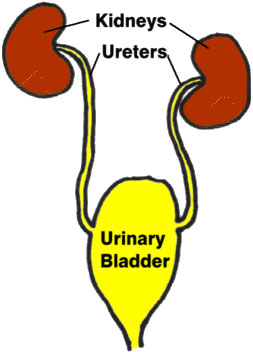

Renal canal illustration

Graphic Courtesy of MarVistaVet

The urinary tract infection is one of the most common ailments in small animal practice, yet many pet owners are confused about the medical approach. Some common questions are:

- Are bladder infections contagious?

- Why do I have to use the entire course of antibiotics if my pet is obviously better after a couple of doses?

- What is the difference between doing a urinalysis and a urine culture? Why should both be done?

- What is the difference between UTI and idiopathic cystitis?

The urinary tract consists of the kidneys, ureters (tubes that carry urine to the bladder for storage), the urinary bladder, the male dog's prostate (which encircles the bladder neck), and the urethra that conducts urine outside the body. A urinary tract infection could involve any of these areas, though most commonly, when referring to a urinary tract infection, or UTI, what is meant is actually a “bladder infection.” Because bladder infections are localized to the bladder, there are rarely signs of infection in other body systems: no fever, no appetite loss, and no change in the blood tests. (If the infection does ascend all the way to the kidneys, then we may well find other signs and other lab work changes. While a kidney infection is technically also a urinary tract infection, we usually use the term pyelonephritis to describe a kidney infection.)

It is also important to note that the term UTI is frequently erroneously used to refer to feline idiopathic cystitis, a common inflammatory condition of the feline bladder affecting young adult cats. It is not a bladder infection.

Feline_urachal diverticulum_cms_resizeto_320x320.j - Caption. [Optional]

![Feline_urachal diverticulum_cms_resizeto_320x320.j - Caption. [Optional] Drawing of a cat showing the kidney and graph of diverticulum](/AppUtil/Image/handler.ashx?imgid=9000054)

Bladder Infection: What Does it Look Like and Where Did it Come From?

The kidneys make urine every moment of the day. The urine is moved down the ureters and into the bladder. The urinary bladder is a muscular little bag that stores the urine until the body is ready to get rid of it. The bladder must be able to expand for filling, contract down for emptying, and respond to voluntary control.

The bladder is a sterile area of the body, which means that bacteria do not normally reside there. When bacteria (or any other organisms, for that matter) gain entry and establish growth in the bladder, infection occurs, and symptoms can result. The key is establishing growth, as sometimes bacteria are just passing through, causing no harm, and disappear quietly. It can be tricky to see bacteria in a urine sample and determine if they are trouble or not. An important measure of whether there is a genuine infection or not is whether the pet has symptoms. People with bladder infections typically report a burning sensation while urinating. Some of the following signs seen in pets are:

- Excessive water consumption (though there is some controversy about this).

- Urinating only small amounts at a time.

- Urinating frequently and in multiple spots.

- Inability to hold urine for the normal amount of time/apparent incontinence.

- Bloody urine (though an infection must either involve a special organism, a bladder stone, a bladder tumor or be particularly severe to make urine red to the naked eye).

Lack of obvious symptoms does not mean that no treatment is needed. Some animals are simply not observed closely enough for their caretakers to recognize symptoms. Some patients are elderly, immunosuppressed from medications or other medical conditions, or have complicating factors, such as a history of bladder stones. For these patients, it may be best to take a proactive approach and not wait for obvious symptoms.

The external genital area where urine is expelled is teeming with bacteria. Bladder infection results when bacteria from the lower tract climb into the bladder, defeating the natural defense mechanisms of the system (forward urine flow, the bladder lining, inhospitable urine chemicals, etc.). A bladder infection is not contagious.

- Bladder infection is somewhat unusual in cats under the age of 10 years.

- Bladder infection is somewhat unusual in neutered male dogs.

Testing for Bladder Infections

There are many tests that can be performed on a urine sample, and people can get confused about what information different tests provide.

Urinalysis

Urinalysis is an important part of any laboratory test database. It is an important screening tool to determine whether an infection is suspected. The urinalysis examines the chemical properties of the urine sample, such as the pH, specific gravity (a measure of concentration), and amount of protein or other biochemicals. It also includes visually inspecting the urine sediment to look for crystals, cells, or bacteria. This test often precedes the culture or lets the doctor know that a culture is in order. Indications that a culture of a urine sample should be done based on urinalysis findings include:

Graphic Courtesy of MarVistaVet

- Excessive white blood cells (white blood cells fight infection and should not be in a normal urine sample except as an occasional finding).

- Bacteria are seen when the sediment is checked under the microscope. (You would think that bacteria alone would confirm infection, but as mentioned, bacteria sometimes pass through urine without stopping and establishing an infection. Other criteria, such as symptoms of inflammation and white blood cells, must be considered.)

- Excessive protein in the urine (protein is generally conserved by the urinary tract). Urine protein indicates either inflammation in the bladder or protein-wasting by the kidneys. Infection must be ruled out before more serious kidney diseases.

- Dilute urine. When the patient drinks water excessively, urine becomes dilute, and it becomes impossible to detect bacteria or white blood cells so a culture must be performed to determine if there are any organisms. Further, excessive water consumption is a common symptom of bladder infection and should be pursued.

- If the patient has symptoms suggestive of an infection, a urinalysis need not precede the culture; both tests can be started at the same time.

Urine Culture (and Sensitivity)

This is the only test that can confirm and identify bacteria in the urine. In this test, the urine is spun down in special equipment to separate the liquid from the solids.

In this test, a tiny urine sample is transferred to a specialized container and incubated for bacterial growth. This is like planting seeds in the soil and seeing what kind of plants grow, if any.

The growth of bacteria on the culture plate confirms there are bacteria in the urine. In addition, once bacterial colonies are growing, the type of bacteria can be identified, the number of colonies can be counted, and the bacteria can be tested for antibiotic sensitivity. Knowing the concentration of bacteria in the sample helps determine if the bacteria cultured might represent contaminants from the lower urinary tract or transient bacteria that are not truly colonizing the bladder. Similarly, knowing the species of bacteria also helps determine if the bacteria grown are known to cause disease or are likely to be innocent bystanders. The antibiotic profile tells us what antibiotics will work against the infection. There is, after all, no point in prescribing the wrong antibiotic. Clearly, the culture is a valuable test when infection is suspected. Current guidelines recommend that antibiotic choices be based on culture results whenever possible.

Urine culture results require at least a couple of days, as bacteria require this long to grow.

Sample Collection

Urine collection illustration

Graphic Courtesy of MarVistaVet

There are four ways to collect a urine sample: table top, free catch, catheter, and cystocentesis. A table top sample is collected from the exam table or other surface where the patient has deposited urine. This sample is likely contaminated with bacteria from the environment and/or bacteria from the lower urinary tract. This is the least desirable urine collection method but sometimes it's the only option. If bacteria are grown, their numbers and species provide a strong clue as to whether or not they represent infection or contamination.

A free catch sample is obtained by catching urine mid-air as it is passed. The sample may be contaminated by the bacteria of the lower urinary tract but will not be contaminated by the floor or other environmental surface.

With the catheter method, a small tube is passed into the bladder and the sample is withdrawn. This is not the most comfortable method for the patient, though the procedure is fairly quick. Potentially, bacteria can be introduced into the bladder accidentally with the catheter, so this represents a drawback, though fortunately, this is a rare occurrence (assuming the catheter is only for urine sample collection and not placed for longer-term urine collection). The sample obtained is unlikely to be contaminated and should represent urine as it exits the bladder.

The ideal collection method is cystocentesis: a needle taps directly into the bladder. In this way, an uncontaminated sample is collected directly from the bladder. Sometimes, a little blood enters the sample during the needle stick, but for culture purposes, the sample can be considered pristine.

Treatment for Simple (Sporadic) Infection

The International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Disease (ISCAID) determines guidelines for classifying UTIs and how to treat them. The simplest type of UTI is called the sporadic infection, which means the patient has had less than three UTIs in the preceding 12 months. The UTI is diagnosed based on the urinalysis and patient history. The sample is cultured to get a list of effective antibiotics, and the patient is treated. Symptoms should obviously improve within 48 hours of starting the correct antibiotic.

How long treatment should continue is controversial. The traditional duration is 10-14 days of antibiotics. In an effort to reduce antibiotic resistance among the world's bacteria, the effectiveness of shorter durations has been explored. ISCAID currently recommends shorter courses, such as three to five days. Your veterinarian may select either of these strategies.

Post-treatment urinalysis or culture may be recommended to confirm that the infection is resolved. However, the most important aspect determining the conclusion of treatment is whether or not the patient still has symptoms.

Treatment of Recurrent Infection

Recurrent infection is defined as more than three UTIs in the preceding 12 months or two or more UTIs in the preceding 6 months. This definition is a somewhat more complicated situation. Culture results are especially important as they will help determine if a UTI simply did not resolve with prior treatment or if a whole new infection has started. Imaging of the urinary tract to look for complicating factors such as bladder stones, polyps, kidney involvement or some other situation is preventing cure. Further, post-treatment cultures become more important.

Here are some factors to explore when infections continue to emerge:

Kidney Infection (Pyelonephritis)

If the patient’s immune system is not ideal, the infection in the bladder may ascend into the kidneys, which can affect kidney function.

There is currently no good test to determine whether or not a kidney is infected. However, there might be hints on the lab work (urinary tract infection in combination with fever, elevated white blood cell count, pain in the area of the kidneys). Ultrasound can help, and there are specific radiographic studies that can help as well. Obviously, kidney involvement is a more serious condition. Traditionally, antibiotics are given for a long time (four to six weeks). ISCAID has amended this to follow current human guidelines of a 14-day course of treatment. Your veterinarian may choose either course or something in between.

Bladder Stones

Stones in the bladder can cause infection, and infection can cause stones. Click here for more information on bladder stones.

Urachal Diverticulum

In embryonic life, urine is removed from the body via the umbilical cord. A structure called the urachus exits the top of the bladder and enters the umbilical cord so urine can be dumped into the mother's bloodstream for removal by her kidneys. After birth, the urachus degenerates, but sometimes a small nipple-like protrusion exists on the top of the bladder. This section can protect a bladder infection in which case recheck cultures will reveal the same organism over and over until the urachal diverticulum is surgically removed.

Bladder Tumors

Bladder tumors, with or without infection, often create symptoms similar to those of a severe bladder infection. The tip-off to look for a tumor is that infection and/or symptoms do not clear up with an appropriate antibiotic course, urine is bloody, and there are no bladder stones on radiographs. The most common bladder tumor is transitional cell carcinoma. (The article on this topic includes more information on detecting this tumor; often, an ultrasound is needed to image the inside of the urinary bladder.)

Prostatitis

The prostate gland is located at the neck of the bladder, and due to its glandular nature, infection in the bladder readily spreads to the prostate, where the crypts and crannies are particularly protective against the infection. It is nearly impossible to clear the prostate of the infection without neutering. Small abscesses within the prostate may require drainage using ultrasound guidance. Only certain antibiotics are capable of penetrating the prostate to reach the infection. Bacterial prostatitis can be a complicated situation.

Vaginal Stricture

Sometimes, when an infection simply cannot seem to be cleared up, the reason is a vaginal stricture. A vaginal stricture is a small narrowing in the vagina that creates a ledge for bacteria to colonize. If a female dog's UTI seems stubborn against antibiotics that the culture indicates should be effective, a vaginal exam may be warranted. A stricture can generally be broken down by the veterinarian's finger, though some dogs find this painful and sedation may be needed.

Most urinary tract infections are straightforward and require only a relatively short antibiotic course for clearance.