Diagram of the normal heart. The left ventricle is shown in pink. Graphic by MarVistaVet

Unless you are familiar with the anatomy of the heart, its outflow tracts, and the aorta itself, some basic explanation helps to understand subaortic stenosis and why it is bad. Subaortic stenosis (also simply called SAS) is a scar-like narrowing, which is called a stenosis, located under the aortic valve. Let's back up a bit and cover how things are supposed to work in the heart.

Let's Start with the Normal Situation

The heart sits more or less centrally in the chest and is divided into a left side, which receives oxygen-rich blood from the lung and pumps it to the rest of the body, and a right side, which receives “used“ blood from the body and pumps it to the lung to pick up fresh oxygen. Because the left side of the heart must supply blood to the whole body, its muscle is especially thick and strong. Blood is pumped from the left ventricle (the pumping chamber) to a particularly large blood vessel called the aorta, the body’s largest artery. The valve that separates the left ventricle from the aorta is called the aortic valve. The left ventricle narrows as it leads to the aorta, and this area is called the left ventricular outflow tract.

In subaortic stenosis, the left ventricular outflow tract just below the aortic valve has a scar-like narrowing called a stenosis. This means that the left ventricle must pump extra hard to get the correct blood volume through the narrowed area. The high-pressure blood squirts through in a turbulent fashion, which creates a sound known as a heart murmur. Any cause of turbulent blood flow can be heard as a murmur; a murmur does not always indicate disease, but a murmur is usually the first sign that the puppy in question might have SAS.

The most commonly affected breeds for SAS include the Golden Retriever, Rottweiler, Newfoundland, Great Dane, Boxer, German Shepherd, German Short-haired pointer, and Dogue de Bordeaux.

When a puppy with SAS is born, the stenosis is very small, barely a ridge near the valve, but over the first six months of life, the stenosis grows, and the murmur (hopefully) becomes more apparent.

The murmur is best heard on the left side of the chest at the level of the base of the heart, right over the aortic valve. The louder the murmur, the worse the obstruction of the valve. The murmur is famous for radiating its sound up the carotid arteries of the neck, making a murmur that can be heard with a stethoscope unusually far forward.

Over time, the muscle of the left ventricle thickens and grows due to the excess work it must perform. Eventually, this interferes with the pumping chamber’s flexibility and ability to fill. Abnormal muscle in the heart makes for abnormal electrical conduction in the heart and soon the heart’s normal electrical rhythm is disrupted. Since pumping and filling are highly coordinated electrically, when this coordination is lost, fainting spells or even sudden death during exercise can result. Most dogs with SAS do not survive beyond age 3 years without treatment, though dogs with milder cases can have normal life spans. A dog with SAS is always predisposed to electrical arrhythmia, heart failure, and infection of the abnormal aortic valve.

The disease is mildest when the puppy is really young and gets worse over the first 6 to 12 months of life.

Recognizing the Disease

Obviously, the pup is not going to receive proper management unless the condition is recognized. The first step is hearing the murmur.

As mentioned, the murmur is the sound made by turbulent blood flow. In other words, a murmur is a sound that might or might not indicate heart disease. Puppies under the age of six months sometimes demonstrate what are called innocent murmurs, which are simply temporary turbulent blood flow. Innocent murmurs should disappear by age six months so that any murmur that persists beyond this time should be pursued as potentially abnormal. This does not mean that you should wait until the puppy is six months of age to attempt diagnosis. The sooner a diagnosis is made, the sooner treatment can begin, and a valid prognosis can be given. There are some size limitations with regard to the equipment needed to assess the puppy, however. Your veterinarian will guide you as to when it is best to pursue the next step in diagnostics.

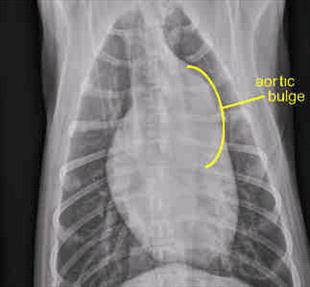

subaortic stenosis radiograph

Chest radiograph of a puppy with SAS. The bulge of the aortic valve is conspicuous. (Photo used with permission by ASEC Cardiology)

After the Murmur

Radiographs are helpful in assessing any evidence of heart failure and may even show a dilation of the aorta near the valve (caused by the high-pressure squirt of blood through the narrowing). This said, the real key to diagnosis is ultrasound, or echocardiography, where chamber sizes and heart wall thickness are measured. Generally, the cross-sectional area of the left ventricle outflow tract is compared to that of the aorta in a ratio to assess the severity of the stenosis. This information is generally adequate to confirm the diagnosis, though a mild case might have values that overlap the normal range. Such a patient might have to be followed over time.

One of the most important aspects of the echocardiography evaluation is the Doppler study. This involves measuring the pressure difference across the stenosis, which essentially tells us how hard the heart is working to eject blood through the narrowing. This information is correlated with survival time and the need for treatment. A pressure difference of 40 mm of Hg (pressure is measured in millimeters of mercury, abbreviated mm of Hg) is mild whereas a pressure difference of 80 mm of Hg is severe. Mildly affected dogs may not require treatment at all.

Treatment: Drugs

The goal of treating SAS is to create normal exercise tolerance and a normal life span. The most popular class of drug for SAS are the beta blockers. Beta receptors are the neurologic areas on the heart that respond to adrenaline (we call it epinephrine now) and cause the heart rate to speed up during exercise. In SAS, this kind of racing pulse is what leads to the abnormal electrical rhythm and, ultimately, to fainting. The beta blockers keep the heart from racing. In one study, dogs with SAS treated with a beta blocker called atenolol had a median survival of 56 months vs. 19 months for dogs receiving no treatment.

Treatment: Exercise Restriction

Fatal heart rhythm episodes in SAS patients are associated with excitement and demanding exercise (though sudden death can certainly occur without either situation). It is probably best to avoid strenuous exercise if possible.

Treatment: Surgery

Open heart surgery is uncommonly performed in dogs, but it is possible to surgically excise the collar of scarring that is narrowing the outflow tract. You would think this would solve the whole problem, but in fact, resulting survival times are similar to those for dogs simply taking atenolol.

Treatment: Balloon Valvuloplasty

With balloon valvuloplasty, the patient is anesthetized, and a catheter is threaded into the heart so that it spans the stenosis. The catheter has a tough balloon at the end, which is then inflated, breaking down the scarring and dilating the stenosis. Again, you would think that this would solve the problem, but survival times are similar to those for dogs simply taking atenolol.

At this time, invasive procedures cannot be recommended over medication. More complete studies in the future may change.

Subaortic stenosis is a genetic disease. Because inheritance is not simple, dogs with mild disease may produce puppies with severe disease. No dog with subaortic stenosis of any degree should be bred.