Most of us have some idea of what happens when someone has a stroke: they are going along normally, and then suddenly, a group of nerves does not work. This might involve an inability to move certain muscles (arm, face, etc.), or it could involve deeper, more crucial neurologic functions in such a way that the affected person dies. (In fact, stroke is the third most common cause of human death after cancer and heart disease.) Most of us know that a stroke involves some kind of blood clot plugging a blood vessel in the brain, preventing an important area from receiving circulation. Most of us also know that sometimes the symptoms of a stroke are reversible or partly reversible, but we don’t know what separates the reversible stroke symptoms from the irreversible ones.

In this discussion, we are going to be reviewing strokes and other vascular accidents in the brains of pets.

But First a Note on Vestibular Disease

Nystagmus. Graphic Courtesy of MarVistaVet

If you have come here seeking information regarding a dog or cat that has a head tilt to one side, perhaps falling toward that same side, and rapid back-and-forth darting of the eyes, you are in the wrong classroom. The subject you want to read about is vestibular disease, which is generally not caused by a vascular accident but is often incorrectly referred to as a stroke. A vascular accident could produce a vestibular syndrome, but chances are greater that a vestibular patient has another underlying condition. If your pet has vestibular disease, you should probably read the article section on that instead.

Is a Vascular Accident the Same as a Stroke?

The short answer is that stroke and vascular accident are the same thing, but there is actually more to a vascular accident than a blood clot lodging or forming in an inappropriate place. Other vascular accidents include a small area of bleeding in the brain, a small blood vessel tumor interfering with circulation, a temporary blood vessel spasm, or even an area of inflammation that alters blood flow. The bottom line is an area of the brain gets deprived of circulation (and thus of oxygen), the neurons (cells that make up the nervous system’s electrical wiring system) are injured or killed, and function is lost. What the function loss might look like is completely dependent on the area of the brain involved. Here is a list of some of the possible clinical signs, with an illustration of the four brain regions below.

Brain Region and Clinical Signs

Vascular accident is non-progressive after the first 72 hours. Graphic Courtesy of MarVistaVet

Telencephalon

- Change in mental alertness

- Loss of certain eye reflexes on the side opposite the brain damage

- Loss of sensation of the nose on the side opposite the brain damage

- Weakness on the side opposite the brain damage

- Circling towards the side of the brain damage

- Drunken gait

- Head pressing

- Seizures

Thalamus or Midbrain

- Crossed eyes

- Head tilt or turn towards the side of the brain damage

- Postural defects

- Loss of certain eye reflexes on the side opposite the brain damage

- Back and forth eye movements

Cerebellum

- Drunken gait

- Loss of certain eye reflexes on the side of the brain damage

- Head twisted backward or upward

- Measuring steps incorrectly

- Tremors during intended actions

- Back and forth eye movements

- Head tilt

- Rigid neck and body

Brain Stem: Midbrain, Pons, or Medulla

- Head and neck pain

- Problems with the reflexes of the head and face

- Altered states of consciousness

- Weakness in all four legs

- Postural defects

- Head tilt and back-and-forth eye movements

Vascular accident is non-progressive after the first 72 hours.

Factors Increasing Risk

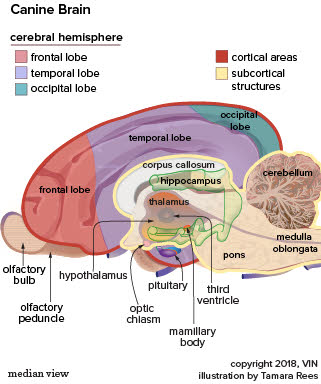

Canine brain anatomy

A more formal look at a canine brain. Graphic by VIN.

As far as human patients go, most of us are familiar with the risk factors as they are emphasized in public service announcements: smoking, diabetes mellitus, high blood cholesterol levels, alcohol use, and history of heart attack. Most of these problems are simply not relevant to pets, which makes vascular accident a much less common condition in pets than it is in humans. That said, an underlying disease can be found in approximately 50 percent of dogs with vascular accidents and 30 percent of dogs with vascular accidents will have high blood pressure. In dogs, the most common factors increasing the risk of vascular accident are:

Other risks include heartworm disease, particularly if a larval heartworm gets lost during migration and ends up in the brain (an example of aberrant migration). Also, the use of phenylpropanolamine, a medication removed from the human market because of increased stroke risks, is still common in dogs as treatment for urinary incontinence. This medication has been implicated, albeit rarely, in cases of canine vascular accidents. Additional causes include atherosclerosis (cholesterol plaques as humans get) associated with hypothyroidism, hypertriglyceridemia (elevated blood fat levels) in miniature schnauzers, and cancer.

In cats, common underlying diseases would be:

Diabetes mellitus, cancer, migrating heartworm larvae, and migrating Cuterebra (a type of fly) larvae probably deserve at least an honorable mention as well.

How to Tell if There Has Been a Vascular Accident

The pet with sudden neurologic symptoms could very well be a victim of vascular accident but may also have suffered some other condition such as head trauma, metabolic disease, poisoning, cancer, or even infection or inflammation. Vascular accidents are characterized by sudden onset that may progress over 24-72 hours, followed by slow or partial recovery. (Of course, death is possible if the initial injury is severe enough.) Accidents involving bleeds tend to be more severe than those involving obstructive clots as they involve larger areas of the brain. Fortunately for dogs (and unlike the situation in humans), bleeding accidents (hemorrhagic stroke as from an aneurysm) are far less common than clotting accidents (embolism or thrombosis).

The first step is going to be basic metabolic blood and urine testing, plus a measurement of blood pressure. Other tests may be indicated depending on the patient’s specific history and the initial test findings. Ultimately, MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is needed to detect hemorrhage, blood clots, or simply damaged areas of the brain. Radiography is not adequate as imaging of the brain tissue through the skull bones is not really possible with this technique. CT (formerly called CAT scanning) is not as sensitive in its ability to pick up blood clots and damaged brain areas but is a fair second choice if MRI is not available. Thromboelastography (TEG) testing is another blood test that can also be used to help distinguish a vascular accident from some other type of neurologic condition.

Treatment

Treatment of vascular accidents is all about supportive care: maximizing brain oxygenation until the damaged nerves can heal. If seizures are occurring, they must be suppressed with medication. If the pressure inside the skull is elevated, it must be normalized. High blood pressure must be corrected, as must abnormal bleeding states. Patients can be affected such that they need special home care, such as help with mobility and toilet function. Physical therapy may be helpful in regaining function. Some patients, however, are so compromised that they need intensive nursing in the hospital, at least temporarily. This could include a feeding tube, supplemental oxygen or even a ventilator to assist breathing, depending on how much loss of function has occurred.

Treatment of the vascular accident patient is basically supportive; there is no specific treatment as yet supported by scientific evidence and investigation. There are, however, many treatments that might be employed based on theory. Calcium channel blockers, amlodipine in particular, appear to be protective of neurologic tissues if administered in the first six hours after the event. Antioxidants such as SAMe make logical sense, but controlled studies in animals have not been performed. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has been advocated to improve oxygenation of compromised brain tissue so as to minimize the area of permanent damage.

Recovery

In humans, the degree and speed of recovery depend on the size of the brain area involved, the location of the brain area involved, the cause of the vascular accident, and the progression of the clinical signs after the initial event. In a study of 33 dogs with vascular accidents, none of these things correlated with outcome. Instead, dogs that had known underlying diseases (i.e., where the cause of the vascular accident was known) had shorter survival times and increased risk of recurrence. As a rule, pets are felt to have a higher potential for recovery than humans (with recovery times typically measured in days to weeks).

Ask your veterinarian about a possible referral to a neurologist or a physical therapist.