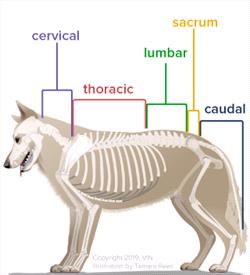

Canine skeleton with spinal sections

The spine is divided into cervical (neck), thoracic (upper back), lumbar (lower back), sacral (connecting the spine to the pelvis), and coccygeal (tail) sections. Copyright VIN Illistrations, Tamara Rees

Vertebrae and the Spinal Column

In vertebrates, the delicate spinal cord (the part of the central nervous system connecting the brain to the rest of the body) is surrounded and protected by a bony tube that is made up of a series of bones (vertebrae), linked together by discs made of cartilage, ligaments, and muscles. This entire grouping is referred to as the spine.

How Does Spina Bifida Develop?

The vertebrae form in the embryo (earliest stages of development) during the mother’s pregnancy. Sometimes, abnormal growth and development of the spine happen before birth with both puppies and kittens. The result is that some of the neural tube, the part of a fetus that eventually develops into the brain and spinal cord, fails to close into a complete tube. This usually occurs on the back side (dorsal or posterior side), resulting in a defect in the affected vertebrae. This congenital (trait present at birth) defect is called spina bifida. Sometimes only the bones are involved, and the defect may cause no symptoms. This is called spina bifida occulta and is usually found incidentally on X-rays taken for other reasons. In other cases, however, the defect in neural tube growth and closure involves the membranes surrounding the spinal cord (called the meninges) or leaves a defect in the spinal cord itself. These defects usually result in clinical signs termed spina bifida manifesta.

Because spina bifida manifesta most often affects the area of the low lumbar and sacral regions in affected puppies and kittens (most often Old English Bulldogs and Manx cats), the signs can include abnormal control of urination and bowel movements, as well as movement abnormalities in the pelvic (hind) limbs.

Another common finding in patients affected with spina bifida manifesta is tethered (spinal) cord syndrome, where the end of the spinal cord is abnormally attached to the spine. As the puppy or kitten grows, the spinal cord cannot expand along with the spine, stretching the spinal cord and leading to further neurological problems.

How Common is Spina Bifida?

Spina bifida is relatively rare in dogs and cats, and the disease can vary from mild to severe.

Human parents of babies with spina bifida are told that no two cases are alike because the symptoms vary in severity depending on where the vertebrae have not closed and by how much is exposed, and the same is true for dogs and cats.

Spina bifida can occur because of genetic factors, problems with nutrition, or if the mother was exposed to certain chemicals and toxins while pregnant. It’s possible that inbreeding and selective breeding practices may increase the likelihood of this condition. English bulldogs and the tailless Manx cats are the breeds most affected by spina bifida, but it can happen to any breed of dog or cat. In brachycephalic or short-faced dog breeds such as English bulldogs, French bulldogs, or Pugs, spina bifida tends to occur at the first thoracic (chest area) vertebra but can be found in different lower areas of the spine as well.

Cats and dogs with spina bifida may leak cerebrospinal fluid, or CSF, from sacs near their tail area. CSF is essential to cushion the spinal cord and keep the spinal cord healthy.

Screw tail dog breeds such as English bulldogs, French bulldogs, Pugs, and Boston Terriers are also known to develop a similar yet different spinal condition called hemivertebra. With hemivertebra, vertebrae are deformed, and two or more may fuse together, which has the potential to cause walking and elimination (urination or feces) issues depending on the location of the deformity on the spine. However, most hemivertebra lesions are not associated with clinical signs.

Diagnosis

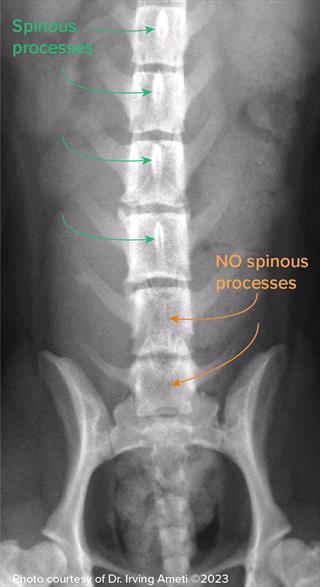

X-ray showing canine spina bifida.jpg

X-ray showing canine spina bifida. Note that some vertebrae are missing spinous processes (bony projections on the backside of each vertebra) due to incomplete development of the spine. Photo courtesy of Dr. Irving Ameti (2023)

Diagnosis includes X-rays, myelography, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine. Myelography involves injecting a contrast dye into the fluid around the spinal cord before an X-ray is taken so lesions may be seen more clearly. It is used specifically to diagnose spinal cord issues. It is often used when other advanced imaging is unavailable.

Myelography is more informative to veterinarians than a regular X-ray but not as clear as a CT or MRI. Myelography can also be combined with CT (they are not mutually exclusive). MRI is the most preferred imaging choice for spinal conditions and is preferable to plain X-rays, X-rays with myelography, or CT with myelography.

Pets are generally sedated for these imaging procedures, so accurate imaging can take place without movement or undue stress to the animal. They may have an IV catheter placed, a sedative is given, and then wake up before returning home after their imaging.

Treatment

Spina bifida may be a minor or major issue for your pet, depending on how many vertebrae did not close properly and where those incomplete vertebrae are located.

Severe cases are considered untreatable, and unfortunately, the pet will have a very poor quality of life due to pain, paralysis, weakness, neurologic deficits, and little ability to control their bowel and bladder. Typically, puppies and kittens are euthanized immediately upon diagnosis of severe spina bifida, and signs that something is not normal can be seen as soon as the puppy or kitten begins to walk.

In minor cases, generally, no treatment is needed. Most of these cases are found coincidentally on X-rays taken for a separate concern. Supportive care can help manage fecal and urinary incontinence, urinary tract infections, and hygiene issues.

- Mild cases can often be treated with reconstructive surgery that removes tumors and cysts, closes sacs, and sometimes may restore part of the spinal cord. Discuss with your veterinarian whether referral to a surgical specialist is best for you and your pet.

- Medications can help with urinary and fecal incontinence, and your veterinarian can offer options for pain control.

- Physical therapy and rehabilitation can help with mobility and strengthen weak muscles.

- Wheelchairs and braces may be recommended.

- Diet may be modified to help manage specific issues and ensure your pet is getting adequate nutrition.

Wheelchairs are helpful for all different kinds of mobility issues.

Wheelchairs can add quality of life for patients with all kinds of mobility issues.

Prevention

Currently, veterinarians don’t know exactly how spina bifida is inherited. It is possible that exposure to chemicals during the growth of kittens and puppies in the mother’s womb could cause abnormal spine development. Still, more research is needed before any recommendations can be made. The only preventive measure currently is to avoid breeding affected dogs and cats.

Prognosis

Prognosis is good for clinically normal pets, and some with mild disease can lead good, functional lives. The prognosis for patients with severe nerve damage or lack of function is guarded, and euthanasia may be recommended if no quality of life is possible. If your pet has been diagnosed with spina bifida, your veterinarian can discuss with you how your pet may be impacted physically and what ongoing treatment options and lifestyle changes may look like for you and your pet so you can both have the best quality of life possible.