Most people have never heard of Babesia organisms, though they have caused red blood cell destruction in their canine hosts all over the world for thousands of years. Babesia organisms are spread by ticks and are particularly significant to racing greyhounds and pit bull terriers. Humans may also become infected.

There are over 100 species of Babesia, but only a few are found in the U.S. and are transmissible to dogs. Infected red blood cells are identified and destroyed, thus killing the Babesia organisms within them, but, unfortunately, if many red blood cells are infected, this leaves the host with anemia, a lack of red blood cells. Babesia species continue to be classified and sub-classified worldwide.

The Babesia species that infect dogs in North America are:

- Babesia canis - a larger species of Babesia, transmitted by ticks.

- Babesia gibsoni - a smaller Babesia species that mostly attack pit bull terriers and is transmitted by bite wounds and from mother to unborn puppies. This is the most common Babesia in North America.

- Babesia conradae - a smaller Babesia species that has only been isolated in California.

- Babesia microti is the species of Babesia that infects humans. A "Babesia microti-like" Babesia has been found in dogs in North America.

How Infection Happens and what Happens Next

Rhipicephalus sanguineus: the most common tick to spread Babesia in the United States. Image courtesy of CDC

Infection occurs when a Babesia-infected tick bites a dog and releases Babesia sporozoites into the dog’s bloodstream. A tick must feed for two to three days to infect a dog with Babesia. The young Babesia organisms attach to red blood cells, eventually penetrating and making a new home within the cells. Inside the red blood cell, the Babesia organism sheds its outer coating and begins to divide, becoming a new form called a “merozoite” which a new tick may drink in during a blood meal.

Infected pregnant dogs can spread Babesia to their unborn puppies, and dogs can transmit the organism by biting another dog as well. (In fact, for Babesia gibsoni, which is primarily a pit bull terrier infection, ticks are a minor cause of infection, with maternal transmission and bite wounds as the chief routes of transmission.)

Having a parasite in your red blood cells does not go undetected by your immune system. Infected red blood cells are identified and destroyed, thus killing the Babesia organisms within them, but, unfortunately, if many red blood cells are infected, this leaves the host with anemia, a lack of red blood cells. Often the host’s immune system will begin destroying the uninfected red cells as well, a condition called immune-mediated hemolytic anemia (IMHA). Signs include weakness, yellowing of the soft tissues ("jaundice"), fever, and red or orange-colored urine.

Making matters worse is the fact that animals seem to get sicker than the degree of anemia would suggest so there is more to this infection than the destruction of red blood cells. The severe inflammation that is associated with this parasitism can be overwhelming and completely separate from the anemia. Platelet counts can drop, impairing normal blood clotting (especially a problem with Babesia gibsoni).

An assortment of neurologic signs of can occur with Babesia infection when parasites gather inside the central nervous system and generate a more localized focus of inflammation. In severe cases, there is a lung injury similar to what people with late-stage malaria can experience. Babesia conradae seems predisposed to creating liver disease.

If the acute signs are relatively mild or at least non-lethal, a chronic infection can develop. This is usually without signs, but the dog may continue to be a source of infection by feeding ticks. Relapses can also occur in times of stress.

Because babesiosis is a tick-borne infection, it is not unusual for infected dogs to have other tick-borne infections such as Ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, and others. These infections may interact to make each other more severe.

Young dogs tend to be most severely infected, especially pit bull terriers.

Diagnosis of Babesiosis

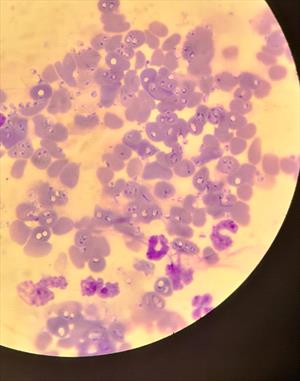

With luck, the Babesia organisms can be seen on a blood smear. Babesia canis organisms are tear-shaped and occur in pairs. Other Babesia species have several forms in which they appear. The odds of finding the organism are improved by checking freshly drawn blood taken from a capillary source (a small cut to an ear, for example) rather than from a blood vessel. If Babesia organisms are found, the patient is definitely infected but in most cases, they are not found so an alternative method of diagnosis is needed.

Severe Babesiosis, Blood Smear, Dog (Microphotograph)

Babesia organisms are seen within erythrocytes and also as extracellular organisms. Courtesy Dr. Rebecca Quam.

Antibody testing has been problematic as infected animals may have circulating antibodies long after the organism is gone or may have no antibodies circulating while the few organisms remain hidden inside red blood cells.

The newest method of diagnosis involves testing for Babesia DNA. This type of testing is called PCR testing and is extremely sensitive, able to distinguish four different species. This is especially valuable information as the different species are sensitive to different medications.

Current recommendations are to do both antibody testing (serology) as well as DNA testing (PCR) as the information is felt to be complementary. If a patient is strongly suspected to be suffering from babesiosis, treatment should begin promptly without waiting for test results. After treatment is completed, PCR testing should be repeated starting 60 days post-treatment and again two to four weeks after that.

Babesia Treatment

Before 2004, an assortment of unpleasant drugs were used against Babesia with mixed success. What medications you will need to use to treat a Babesia infection turns out to depend on which species of Babesia the patient is infected with. There are two Babesia species that are particularly challenging: Babesia gibsoni (the one that involves primarily pit bull terriers) and Babesia conradae (the Babesia found only in Southern California).

Since 2004 a new protocol has emerged for Babesia of either the gibsoni or conradae species using atovaquone and azithromycin in combination. These two medications stop reproduction so that the host's immune system has time to gain the upper hand and remove the organisms without their numbers increasing. Side effects are few to none, and improvement is generally obvious within the first week. Unfortunately, atovaquone is expensive, and pharmacies are reluctant to sell less than an entire bottle. It is often tempting to use the version of atovaquone that comes combined with proguanil, another anti-protozoal drug, but this version has not been evaluated thoroughly against Babesia and is famous for inducing severe nausea in dogs. Imidocarb, one of the earlier treatments, can be started while the correct formulation of atovaquone is obtained; it is best not to use azithromycin alone during that time, or resistance may develop.

If atovaquone simply proves too expensive, the patient can be treated with imidocarb as was done in the past until such a time that it is possible to save up for the atovaquone/azithromycin protocol. Imidocarb creates a remission from the physical illness for an extended time but does not actually clear the infection.

If imidocarb is employed, a single dose is usually effective for Babesia canis but two given two weeks apart are needed for the smaller Babesia species. The injection is painful, plus it causes muscle tremors, drooling, elevated heart rate, shivering, fever, facial swelling, tearing of the eyes, and restlessness. Pre-treatment with an injection of atropine helps palliate these side effects.

Occasionally a strain of Babesia gibsoni is resistant to atovaquone. When this happens, imidocarb can be used as described above with the addition of doxycycline, clindamycin, and metronidazole for a three-month period.

For Babesia canis, two doses of imidocarb, as described above, should generally completely clear the infection. The use of atovaquone appears to be unnecessary.

A vaccine is available against Babesia in France but only seems effective against certain strains. Vaccination is 89% effective in France. The best prevention is aimed at tick control.

Racing Greyhounds

A racing greyhound. Courtesy MarVistaVet

Since areas where greyhounds are professionally raced tend to be areas with ticks, racing greyhounds are commonly infected with Babesia. Whether these infections become active remains to be seen as the carrier state seems to be common in infected dogs. As racing greyhounds end their careers and enter the adoption system, Babesia infection is commonly screened. An apparently healthy but positive-testing dog can still be adopted with the understanding that active infection is unlikely but possible. Such a dog could transmit her Babesia infection to other dogs via ticks or bite wounds and should certainly never be used as a blood donor.

Human Babesiosis

The species of Babesia that infect pets should not pose any problems to people with normal immune systems. People with compromised immune systems or people who have had their spleens removed may have some concerns. In the U.S., babesiosis usually occurs on the East Coast and along the Great Lakes and stems from tick bites. Most signs are mild or easily treated, but a five percent mortality rate has been reported. The usual organism is Babesia microti.

Read more about human infection from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.